The Jones Speedometer Building

by Tom Miller

Joseph W. Jones took a summer job in the 1890’s with a phonograph inventor, Emile Berliner. Quick to learn, he developed his own ideas for improving the device. He received a patent for his process of creating disc records, which he sold for $25,000 to Columbia Graphophone. It was the beginning of a long string of inventions from the young man.

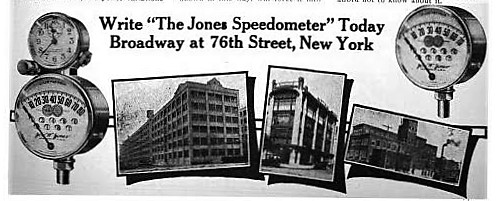

Like the popular gramophone, the automobile provided a fertile field for innovation. In rapid-fire fashion Jones invented taximeters, speedometers, and spring motors. He established a factory in Rochester, New York, and in 1906 laid plans for a new Manhattan showroom, offices and garage (for installing the instruments in buyers’ cars).

At the time the long stretch of Broadway above Times Square was known as Automobile Row. The offices of automobile makers and sellers, as well as tire companies and other related firms lined the thoroughfare for blocks. Now Jones would join the trend.

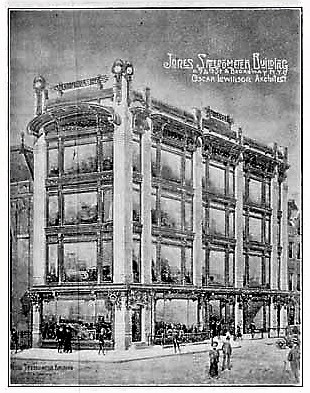

On September 15, 1906 The Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide reported that Oscar Lowinson “has been commissioned to design plans for the Jones Speedometer Co…to be erected on a plot at the northeast corner of Broadway and 76th st.” No one could have anticipated the remarkable structure that emerged from Lowinson’s drafting table.

Six years earlier the Exposition Universelle had opened in Paris. It thrust the Art Nouveau style onto the world stage, in the form of textiles, home decorative articles and jewelry, and in architecture. The style was so identified with the World’s Fair that when Lowinson released his renderings for the Jones Speedometer project, The Record & Guide said “The building is designed in the Exposition type.” But Lowinson did not rely solely on the sinuous French model; he melded other regional takes within the Jones Speedometer Building design.

the building “promises to be the finest sample of architectural ensemble devoted to the automobile business in Manhattan. Mr. Oscar Lowinson, the architect, has spared no pains in making this the finest building of its kind.”

“The Art Noveau [sic] style being particularly fitted for this type of work, Mr. Lowinson availed himself of the experiences of the expositions held in France, Germany and Italy during the past five years to design a structure that would be both an exposition and an advertising building.”

On February 9, 1907 The Record & Guide said that the building “promises to be the finest sample of architectural ensemble devoted to the automobile business in Manhattan. Mr. Oscar Lowinson, the architect, has spared no pains in making this the finest building of its kind.”

Four stories tall, it used a steel-frame construction to enable vast planes of glass. Lowinson then decorated the facade with striking Art Nouveau elements of copper, bronze and iron. Above the ground floor showroom was what the Record & Guide termed “an elaborate cornice extending some distance from the building, supported on ornamental brackets with ornamental grill work over the entrances.” The electric lamps on the piers were giant imitations of the Jones Speedometers, the lettering of the instruments etched into the glass faces.

The upper cornice was spectacular, taking the form of a gently-arched hood on the Broadway elevation. A large frieze below was decorated with gilded discs. Corner piers upheld two other lamps over Broadway, “set in allegorical casings representing ‘flight.’”

The interiors, too, were in the Art Nouveau style. The Record & Guide wrote “The second floor has been laid out in the Art Noveau [sic] and contains the various offices, including the private office of Mr. Jones, the inventor, which has been built in oak wainscot treated characteristically.” The basement was used for shipping, and contained the stockrooms, lathes and machinery for testing and fitting the instruments. The ground floor was an automobile showroom; and the top floor was divided into laboratories and offices.

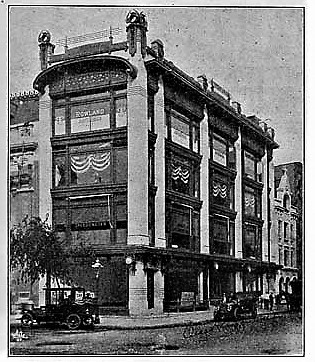

The Jones Speedometer Building was completed in August 1907 at a cost of $500,000–in the neighborhood of $13.5 million today. On September 5th, the press and other guests were invited to tour the building which Automobile Topics called “a model of completeness and commodiousness.”

The Real Estate Record & Guide went further. “Mr. Lowinson prides himself on having constructed the most characteristic building in the automobile district to-day.” It was, in fact, among the most distinctive structures in any part of the city.

Automobile Topics noted “Few men of thirty can point to such achievements as stand to the credit of Joseph W. Jones who has become famous in connection with the speed recording instrument bearing his name. Five years ago he came from Syracuse without a dollar in his pockets, and his energy and inventive genius have in that short time made his name and his product known over the civilized world.

The Automobile focused more on the reporters’ lack of manners. “New York’s long and constantly increasing line of automobiling establishments that are daily going up further north along Broadway received a notable addition with the recent formal opening of the Jones Speedometer building…in which ceremony the newspaper scribes duly assisted by punishing the buffet luncheon.”

Jones Speedometer initially leased the showroom space to United Manufacturers. The wholesaler handled not only Jones products (like its speedometer and Jones Electric Horn), but auto accessories of a few other makers. In May 1910 it moved to No. 239 West 54th Street when it and the tenant there, the Touring Club of America swapped spaces. The club took not only the first, but the third floors in the Jones Speedometer Building. Another tenant, The Automobile Blue Book Publishing Company was in the building by 1913. It was a sign of Joseph Jones’s gradual withdrawal from the automotive business.

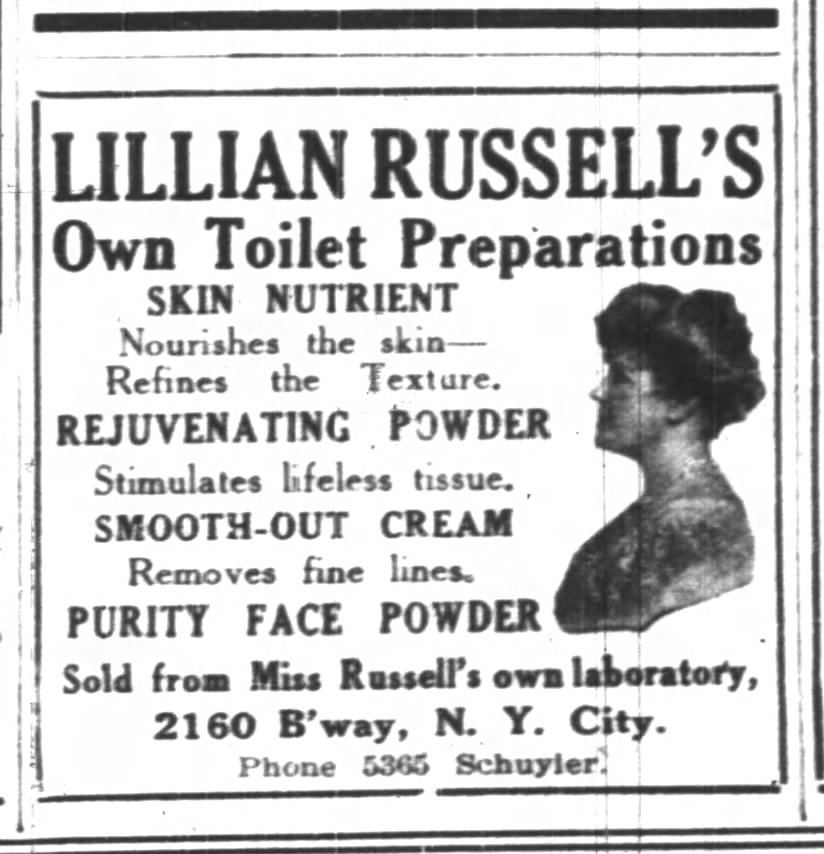

We are accustomed today to celebrities branding their names onto apparel, sneakers and cosmetics. In 1913 stage actress Lillian Russell was ahead of the game. She incorporated Lillian Russell’s Own Toilet Preparations, Inc. and briefly moved into the Jones Speedometer Building before settling next door in 2166.

As mid-century approached Gala Record Co. was in the building. No. 2160 Broadway received four alterations–in 1950, 1953, 1957 and 1968–after which almost no trace of Oscar Lowinson’s singular Art Nouveau design–a rarity in Manhattan–survived.

Always on the cutting edge of inventions, Joseph W. Jones was focusing more and more on radio. In October 1924 he opened a new factory in the Bronx to manufacture his radios and eventually gave up the Broadway headquarters.

The building became home to Friedner & Ebstein, Inc., which listed itself as selling “furniture, interior decorations, works of art.” The firm updated the ground floor, stripping off Lowinson’s Art Nouveau cornice and inventive lighting fixtures and replacing the facade with a sleek black-and-chrome Art Deco surface.

As mid-century approached Gala Record Co. was in the building. No. 2160 Broadway received four alterations–in 1950, 1953, 1957 and 1968–after which almost no trace of Oscar Lowinson’s singular Art Nouveau design–a rarity in Manhattan–survived.

In the last quarter of the 20th century the ground floor was home to Kinsley’s restaurant (the service of which New York Times food critic Mimi Sheraton deemed “well-meaning”). It was the beginning of a long tradition of eateries in the space.

The 1980’s saw four restaurants come and go; followed by Bertha’s Mexican restaurant in 1993, Xando Coffee and Bar in 1997, and Cosi in 2005.

In the meantime, the Jeff Martin Studio provided aerobics classes on the second floor to “housewives and Broadway dancers; [and] at night, three-piece-suit lawyers and Wall Street number-crunchers,” according to director Dianne Feeney in an interview with Times journalist Joanne Kaufman on October 5, 1990. It closed in 1994, prompting The Times‘s Beth Landman to recall that it “dominated the 1980’s fitness scene in New York with driving aerobic dance.”

It was replaced by Crafts on Broadway where children learned sand-art, how to decorate a t-shirt or paint plastic figurines.

Today the building is occupied by a bank; its stark, denuded facade an architectural tragedy.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business currently at 2160 Broadway: