The Aeon Garage

by Tom Miller

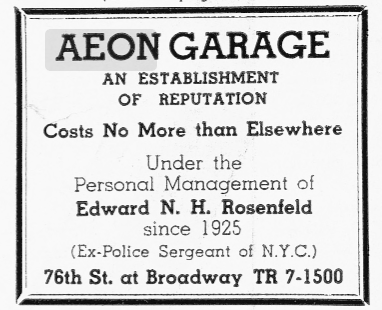

In January 1900 Mary Jane Pinchot purchased the five-story carriage factory on the southeast corner of Broadway and 76th Street from the estate of her father, Amos R. Eno, for $110,500—more than $3.85 million by 2022 standards. Like Amos R. Eno, Mary Pinchot was a major player in Manhattan real estate circles. Sometime before 1913 Mary moved to Washington D.C., and her son, Amos Eno Richard Pinchot, took over the management of the property.

By then, the days of horse-drawn carriages were rapidly waning. Pinchot demolished the old factory, and in November 1913 hired architect Walter Haefeli to design a modern, five-story garage with stores at ground level. His design, a blend of the Arts & Crafts and Chicago styles, featured a chamfered corner that provided extra light and ventilation. The upper floors were faced in variegated brick peppered with terra cotta diamond-shaped tiles.

On October 7, 1914, The Horseless Age reported that the newly formed Aeon Garage Corporation had signed a ten-year lease on “the large five-story garage just completed at the corner of Broadway and Seventy-sixth Street.” The officers christened the structure the Aeon Garage—a name that originally meant “life”,” or “vital force.” The article said the company “proposes to establish here one of the finest public garages in the city.” The Real Estate Record & Guide added that the garage could accommodate 225 cars, and that there were eight stores, seven on Broadway and one on the corner.

The duties of garage employees in 1914 were quite different than in 2022. A former watchman who had injured his leg and lost his job, Andrew Kelly, was hired at the Aeon Garage. During the hearing in his case against his former employer, he was asked “What work did you do?” His answer was, “Polishing.” “Polishing what?” asked the attorney. “Automobiles,” answered Kelly.

the Aeon Garage—a name that originally meant “life”,” or “vital force.”

Unfortunately for Kelly and his bad leg, polishing the brass and chrome on automobiles was not the only work required of him. He lost this job, too. “I got laid off, because I could not push the wagons around; the leg was too sore,” he explained.

Just like livery stables before them, which assisted clients in selling carriages or horses, early garages did the same with automobiles. An advertisement in The New York Times on September 28, 1915, for instance, read: “High-type raceabout, absolutely A1 condition; real sacrifice. Aeon Garage. Broadway and 76th.”

In February 1916, The Suffragists of the 15th Assembly Districted rented the store space at 2150 Broadway. On March 8 the Poughkeepsie Eagle-News reported on the “good record of activity” the group had accomplished in only two weeks. “The women in charge of the headquarters do not forget the domestic arts,” stressed the article. “Every afternoon they entertain, serving tea and home-made cake to all their visitors.”

The following year, in September, Morris Schor leased the space at 2154 Broadway “for a long term as restaurant,” according to the Record & Guide. It remained until 1931 when in May the Aeon Restaurant, Inc. took over 2148 through 2150 for the Steuben Tavern Restaurant. The former Schor restaurant space became Marshall Clarke’s florist shop.

On the afternoon of December 28, 1931, the tavern had no customers, and there were three employees at work when four men walked in. One asked the cashier, Victor Serraroni, for a pack of cigarettes. When he opened the cash register, the man pulled out a pistol and said, “And I’ll take the money, too.”

While his three accomplices held the other workers at gunpoint, the crook grabbed $156. The four then disappeared in a taxicab. Their descriptions were “flashed to all signal boxes and patrolmen were ordered to center in subway stations along Broadway, in the belief the bandits might abandon their cab and try a less conspicuous means of escape,” reported The Standard Union.” At the 72nd Street station, an agent told police that four men had just jumped onto the tracks. One group of police went north on the tracks, another went south. The Standard Union reported, “The lights of a passing train revealed [Frank] Hanley making his way down the track and the chase began.” That chase was heart-stopping. The suspect “was captured after dodging trains and fifteen shots fired by pursuing policeman,” said that article. The writer explained that the chase “ended when Hanley ran into the arms of police at the Sixty-sixth street station.”

The flue from the kitchen of the Steuben Tavern Restaurant ran up the outside of the building. On Saturday morning, September 29, 1934, the flue caught fire. The New York Sun reported that “Several patrons were in the restaurant when the fire was discovered. An employee of the restaurant turned in an alarm.” Before firefighters could arrive, flames shot through a second-story window, slightly damaging an automobile owned by Howard Viet. Luckily, the fire was extinguished after about 20 minutes, with no other vehicles damaged.

When he opened the cash register, the man pulled out a pistol and said, “And I’ll take the money, too.”

The Steuben Tavern Restaurant was replaced by Dilbert’s Super Market in 1959. Its Grand Opening advertisement on July 23 promised, “Here you will discover a new pleasure in food shopping. Air conditioning, gentle lighting and the beautiful pastel color-blended interior will make your shopping trip really pleasant.”

The store at 2154 that year was occupied by Henrietta Himmelforb’s dry cleaning store. She was alone in the store at closing time on July 13, 1959, when 24-year-old Walter Woods dashed in, grabbed her purse, and ran out. It held $60 in cash, two rings, and other personal items. Woods did not get far. Held without bail, he told the arresting officer that “he has no home.”

By the last quarter of the 20th century, the garage was operated by the AVIS car rental company. The stores were home to a variety of tenants in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Among them were Adriana’s Bazaar, Second Stage, and Ernie’s, an Italian restaurant. The aging structure was showing problems by then. At some point before 1988, the cornice was removed, most likely for safety reasons. And on December 4, 1994, The New York Times reported, “Last June, the commercial tenants at 2150 Broadway found themselves temporarily out on the street. Structural problems on the second floor of the building…posed a safety concern and had to be repaired.” By then the cornice of the building had been missing for at least a decade.

Walter Haefeli’s handsome structure was demolished around 2010, replaced by an 18-story apartment building that, not coincidentally, houses an AVIS car rental.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the local businesses at 2150 Broadway aka 216 West 76th Street: