The Royal Garage

by Tom Miller

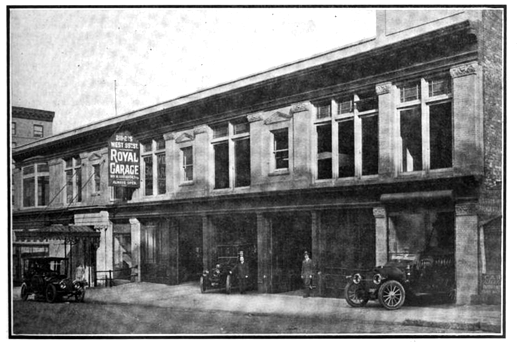

In 1906, a coal yard occupied the northeast corner of Broadway and West 95th Street. At the time, automobiles were gradually replacing horse-drawn vehicles. Four years later, in April 1910, architect L. F. J. Weiher filed plans for a “two-story brick store and garage” on the site for the Real Construction Co. Completed the following year, the 95th Street side housed the Royal Garage. The long Broadway front would hold retail stores and office space. Weiher mixed Arts and Crafts with Romanesque Revival in designing the long, low building. The brick piers between the openings wore carved brownstone capitals with medieval designs.

On October 26, 1912, The Tammany Times called the Royal Garage, “one of New York city’s leading garages,” adding, “The most modern and approved methods of storing gasoline are employed there.” The article pointed out, “The two essential features of a garage are proper care of the machines and absolute safety,” and assured its readers that “the Square Deal House” offered both to its customers.

The Royal Garage offered a complete range of services. Owners could store their automobiles here as well as have them serviced. The Tammany Times wrote, “A full line of supplies for the automobile is carried, including tires and vulcanizers. A specialty is made of the repairing of automobile tires, and the firm enjoys a large trade in this line of the industry.” In addition, the proprietor of the Royal Garage, William Haradon, established a policy by which owners could keep track of the movements of their cars. In its August 15, 1915 issue, The Horseless Age reported,

Complete check is kept on the cars stored in the Royal, every arrival and departure of the vehicles being recorded on time cards which are always at the call of the owners. This practice makes it absolutely impossible for a chauffeur to indulge in “joy riding” without that fact coming to the attention of the owner of the car.”

The Suffrage Pure Food Store sold items obtained only from female farmers and growers.

In the meantime, the commercial spaces on Broadway filled with a variety of tenants, like the hat store of W. Skalla & Co. The American Hatter mentioned in 1913, “Mr. Skalla is an old-time hat man and is practical in every branch of the business.” Another space was occupied by the Century Gas & Electric Fixture Company that year.

An unexpected tenant signed a lease in 1913. While automobiles were transforming the way Americans got around, Suffragists intended to change the way they elected officials. And on February 19, 1913, The Sun reported, “A new dairy and grocery store is to be opened to-morrow at 2540 Broadway, near Ninety-fifth street, financed and run by women…The store is the first to be opened by the newly incorporated Suffrage Pure Food Stores Company.” The article noted that the incorporators were all members of the International Suffrage Club.

The Suffrage Pure Food Store sold items obtained only from female farmers and growers. “The new store will be supplied by women, for its butter, eggs, honey, fresh killed chickens and home cured ham will come from farms owned by women in New Jersey,” said the article. “The delicatessen department will include home made cake, cookies, bread and candy.”

On the grocery’s first day of business, a journalist from the Syracuse Journal was on hand, who reported that the women “did a brisk business.” The article noted, “Everything about the little store was painted white, from the shelves covered with cans and boxes, stamped ‘Votes for Women,’ to the ice boxes containing butter and fresh killed fowls…In the meantime, the three-wheeled yellow suffrage push-cart with ‘Votes for Women’ on the sides, is conveying packages about the neighborhood.”

It was that yellow cart with the suffragist motto that caused problems. The managers soon discovered that their delivery boys, one after another, left the job after a day or two. The New York Herald explained on March 18, “those ‘Votes for Women’ signs on the pushcarts made them a little too conspicuous. They attracted attention from other ordinary but idle little boys and the delivery trips became about as congenial as the reconnaissance of Turks along the Servian border.”

The managers of the Suffrage Pure Food Store came up with a solution. They advertised for “able bodied women who would admit to twenty-five years or more” to deliver the packages for $10 a week. The New York Herald reported, “yesterday morning when the store was opened twenty women were waiting to take the job.” By 9:30 the group had grown to 35, who “almost mobbed Mrs. Kremer and her assistant.”

The managers soon discovered that their delivery boys, one after another, left the job after a day or two.

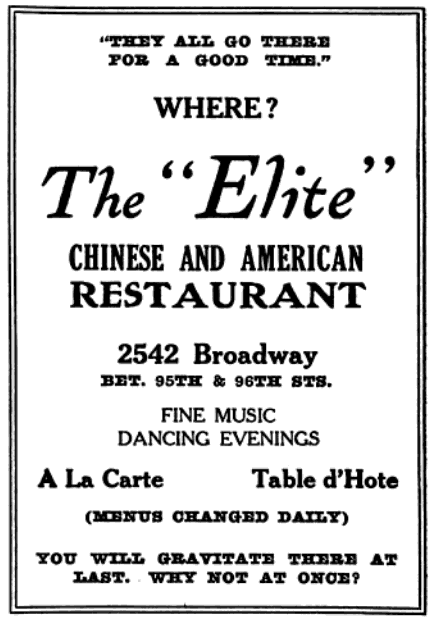

Other tenants along Broadway were the headquarters of the political organization, the Tamarora Club; Womrath’s Circulating Library; a United Cigar Store; and Theodore Theodore’s delicatessen. Coincidentally, in 1921, the same year that Theodore’s deli filed for bankruptcy, the Broadway side of the building was remodeled. There were still stores at sidewalk level, but the second-floor spaces were combined to accommodate The Elite, a Chinese-American restaurant with “fine music” and evening dancing.

Unfortunately for the 80 investors in the upscale club, The Elite filed for bankruptcy in January 1922. One partner, Tom Fay Yee, explained to the New York Herald that it had fallen victim to the scores of “chop suey and plain American restaurants that crowd Broadway about Ninety-sixth street.” They took away his customers, he said, “and the Elite was left with great quantities of chop suey and no one to eat it.” Before long, the cavernous space became home to the Ann Gold Drama and Dance Academy.

By 1923, the Royal Garage had been taken over by the Riverside Garage. The 95th Street section of the building got a makeover in 1932 when architect Anthony Lombardi renovated the two-story garage and added a “chauffeurs’ office” in a new penthouse level.

The Broadway stores continued to see a wide variety of tenants through mid-century. In the late 1940s the real estate office of Morice Haymes was on the second floor, as was the office of the American Labor Party in the mid-1950s. Other tenants were the Laundricoin Company, here in 1959, and the O’Hara Travel Agency in the 1960s. The early 1970s saw the young men’s clothing store Hang Ups at 2540 Broadway. The shop advertised itself as “The house of the Mod Man.”

By then, the end of the line for the two-story building was near. It was demolished to be replaced with Schuman Lichenstein Claman & Efron’s The Princeton House, a 16-story residential structure completed in 1986.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 215 West 95th Street aka 2540-2550 Broadway: