The Hotel Monterey

by Tom Miller

In 1913 the architectural firm of Schwartz & Gross designed the 12-story Apthorp residential hotel at the northeast corner of Broadway and 94th Street for real estate operator Harry Schiff. Completed the following year, the upscale structure had cost the equivalent of more than 6 million in 2023 dollars. Schwartz & Gross’s tripartite, Renaissance Revival design included a two-story stone-faced base, an eight-story brick midsection, and an impressive two-story upper level with double-height piers.

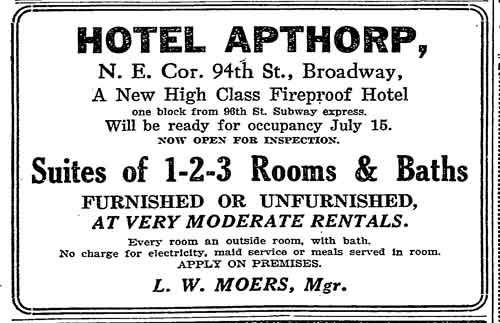

An advertisement for the new Apthorp Hotel called it “a new highclass fireproof hotel, and offered “suites of 1-2-3 Rooms & Baths.” It noted, “No charge for electricity, maid service or meals served in room.”

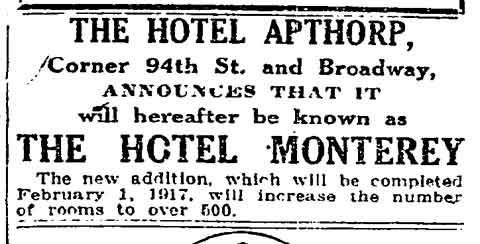

Unfortunately for Schiff, William Waldorf Astor had already taken the name Apthorp for his sumptuous 1908 Apthorp Apartments on Broadway between 78th and 79th Streets. He sued Schiff and won. An advertisement in December 1916 proclaimed that the hotel “will hereafter be known as The Hotel Monterey.” The announcement added that a new addition to the east of the original building “will be completed February 1, 1917.”

The 1917 alterations included the introduction of a restaurant space on the Broadway side. It was leased to the C. & L. Lunch Company, which ran a string of luncheonettes in the city.

The Monterey Hotel had a wide variety of tenants. Among the first were Emanuel DeRoy, a prominent jeweler, and his wife, the former Johanna Aron. Born in Amsterdam, Holland, in 1841, DeRoy came to America with his parents when he was 12. In 1914 the couple celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary, and the following year DeRoy retired “because of ill health,” according to The Jewelers’ Circular-Weekly.

A much different resident was Henry Zimmerman, known as “Heinie Zim” or “The Great Zim” to New York Giants baseball fans. Born in 1887, he began playing Major League Baseball in 1907 with the Chicago Cubs. He was traded to the New York Giants in 1916. On June 25, 1919, The Evening World reported that Zimmerman and Bertha K. Noe had been married the previous evening at the bride’s parents’ home. The article noted, “The couple are at the Hotel Monterey, Broadway and 94th Street, and leave on their honeymoon to-morrow.” (As it turned out, things went downhill for Zimmerman that year. In September he was ousted from the team for trying to convince players to throw games, and never played in professional baseball again.)

“Keep your mouth shut,” ordered Ross, pointing a revolver at him, “or I’ll blow the top of your head off.”

At 4:30 on the morning of December 11, 1919, Frederick Dunne, the night clerk, discovered a fire in a storage room where mattresses and other supplies were stored. He and a police officer tried to extinguish it but were unsuccessful. The Evening World reported, “Bellboys were sent through the building, assuring the guests there was no danger, but many came downstairs in various states of undress.”

The 600 residents had reason to be concerned, since the smoke from the fire traveled up the elevator shafts and into rooms. Despite the cold December air and their nighttime attire, many fled into the street. The article said that garments were their “least worry.” The fire was soon put out by firefighters and the residents went back to bed.

Samuel Ross, described as a “short, stocky, red-haired” salesman around 20 years old by The Evening World, took rooms in April 1920. His intentions were more nefarious than a restful stay. On the night of April 7, Meyer Kriegsman returned to his apartment from dinner and stepped into the bathroom. And there he came face-to-face with the red-haired stranger.

“Keep your mouth shut,” ordered Ross, pointing a revolver at him, “or I’ll blow the top of your head off.”

What Ross did not know was that Kriegsman did not live alone. He shared the apartment with Samuel Guggenheim, who heard the voices. Guggenheim rushed into the bathroom, and “the youth fled,” as reported by The Evening World. Hotel employees searched the hallways, storage rooms, and staircases to no avail. Suddenly, said the article, “it was recalled there was a red-haired guest in the hotel.” Ross was found in his room and arrested, charged with assault and burglary.

Also sharing an apartment in 1920 were Ziegfeld showgirl Betty Martin and model Anna Daly. Anna had grown up in McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania with her best friend, Olive Thomas. The young women were especially close. After Olive’s death that year, Anna Daly became despondent. Betty Martin went on the road to Chicago with the Follies in September. Left alone, Anna departed the Monterey Hotel on September 20 and checked into the Seville Hotel as Elizabeth Anderson. She tacked a note on her door that read, “Do not disturb me.” The Sun reported, “This piqued the curiosity of a maid, and the door was broken in.” In the room was the body of 23-year-old Anna Daly, who had swallowed poison. She left a note that read, “Olive is gone. I can’t stand it any longer.”

In December 1919, wealthy liquor dealer Michael Morrison married his “child wife,” as described by newspapers, Mildred. In August 1921, Morrison moved into the Monterey, without her. His already sensational love story was in the papers again when Anna Dresisiri, Mildred’s legal guardian sued on her behalf (Mildred Morrison was still a minor). In court, the girl testified that her husband told her in August that “he was in love with another woman and cared for her no longer,” as reported by The Evening World. She said he offered her $5,000 if she would divorce him, but she refused.

She left the city for a while, and when she returned, discovered he had moved out of their apartment and “was in Tannersville [New York], where he was reported to be engaged to Elsie Sault.” The stalwart girl went to Tannersville to the home of Elsie Sault’s parents, who confirmed the engagement. The Evening World reported, “When she told them that she was the wife of Morrison, Elsie’s father declared that he would shoot Morrison on sight.” The young girl was awarded $100 a week in alimony and $1,000 legal fees.

A variety of residents continued to occupy the Monterey Hotel through the 1920s and 1930s. Vaudeville performer Loretta Marsille lived here in 1921, and in 1922 Serbian native John Popovich moved in. His stay was rather short. He was arrested in his rooms on December 4 by Secret Service agents. In his apartment was “a bag of counterfeit Bank of England notes,” reported The Evening World. Also living here that year were singer and voice coach Augusta Cottlow, and food products broker Sol Simons.

An especially erudite couple were Alexander Kadison and his wife, the former Isabel Dean. The pair were married in 1921. The extremely well-educated Isabel held two degrees from Columbia University and another from Barnard College. She was an instructor in Classics at Hunter College. Alexander Kadison was an author. Among his works were the 1919 Through Agnostic Spectacles, and the 1922 Immortality: An Agnostic View.

The Kadisons were still living in the Monterey in April 1934, when Kadison placed a notice in The New York Sun that read:

Alexander Kadison is writing a biography of Annie S. Peck, mountain climber and explorer, and he will be glad to receive information concerning her which might be pertinent to his book. His address is 215 West Ninety-fourth street, New York city.

(Interestingly, according to the May 1951 issue of Word Study, Isabel Dean Kadison coined the word “anatomonym,” “to denote a noun describing a part or constituent of the body that can also be used as a verb.” An example would be “elbow.”)

…in 1922 Serbian native John Popovich moved in. His stay was rather short. He was arrested in his rooms on December 4 by Secret Service agents.

By the mid-1940s, the respectable tenor of the residents was eroding. On February 4, 1945, Allen Weinberg was arrested for pickpocketing. The New York Sun noted that he had “a record of forty-four arrests since 1913.” And on September 23, 1947, The Bergen Evening Record reported that 23-year-old Lawrence Klein, alias Kaye, had been arrested “charged with running a swindle that left householders holding the bag for the cost of new siding to their homes.”

A penthouse level was added to the building in 1951. There were now 38 hotel rooms per floor, plus 16 in the penthouse. Within a decade, the Monterey Hotel had become a flophouse. On the morning of September 4, 1964, 72-year-old Regina Weinberger threw herself from the window of her 12th-floor room to her death. The police said she “had been described as despondent by her relatives,” according to The New York Times.

A welfare hotel by 1973, it was the subject of Chantal Akerman’s 1973 film Hotel Monterey. The film was encapsulated by IMDb, which said, “Hotel Monterey is a cheap hotel in New York reserved for the outcasts of American society. Chantal Akerman invites viewers to visit this unusual place as well as the people who live there, from the reception up to the last story.”

On April 4, 1974, The New York Times reported, “Two Japanese women were found dead yesterday in a West Side hotel where they had been living…The bodies were discovered in the Monterey Hotel at West 94th Street and Broadway.” The women had been strangled with electric cords. The murders were two of the three that occurred in the hotel that year.

Once a month, the manager, 54-year-old Louis Parker, would take the tenants’ welfare checks to the bank and cash them. He had just returned with the $4,050 on March 1, 1975, when he was shot to death in the lobby. The shooter, who had apparently followed him from the bank, grabbed the manila envelope and ran. He brushed past two patrol officers in fleeing and was quickly arrested.

Eight months later, Madeleine Ross, the widow of a police officer, was found dead in her room. She had been strangled, and her throat slashed.

And on November 1, 1987, 26-year-old resident Mobulac Suculci got into a dispute with a man who had been staying with him. The unknown second man was seen throwing a Molotov cocktail into the room, which exploded. Suculci, who suffered critical burns, was rescued by firefighters, who extinguished the blaze that was confined to his room.

Change finally came in the early 2000s when a renovation resulted in a Quality Hotel. In 2008 it became a Days Hotel, and in 2021 was renamed the Night Hotel.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 215 West 96th Street aka 2520-2526 Broadway:

Meet Noel Gonzalez!