The Astor Court

by Tom Miller

Following his father’s death in 1890, William Waldorf Astor became the richest man in America. But wealth did not buy contentment. He was unpopular in the press and in 1891 became embroiled in a vicious family feud with his cousin, John Jacob Astor, and his aunt, Caroline Schermerhorn Astor. The warring families lived uncomfortably close to one another in side-by-side mansions on Fifth Avenue between 33rd and 34th Streets.

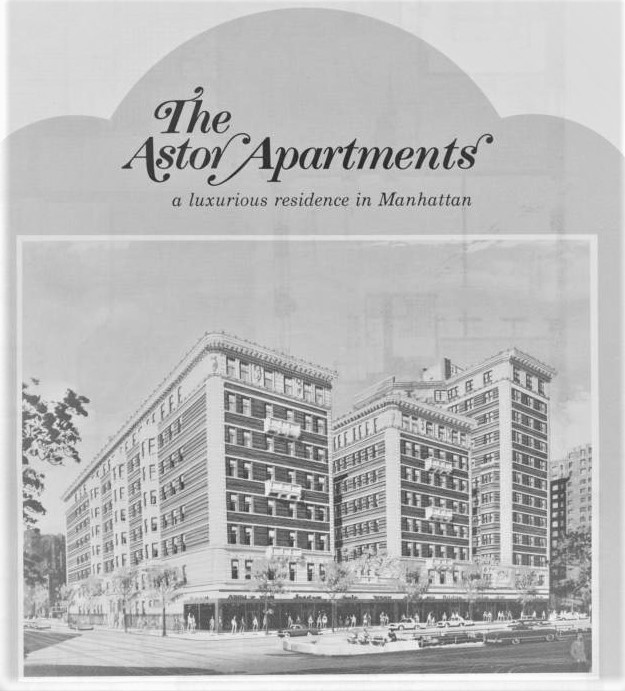

Astor solved the problem by moving his family forever to England. His real estate operations in America were managed by the “Astor Estate” organization. In 1900 the Astor Estate commissioned the architectural firm of Clinton & Russell to design a sprawling upscale apartment building on the northwest corner of 75th Street and Broadway.

Faced in gray brick and limestone, the eight-story Renaissance Revival style building was completed in 1901. Its U-shape provided light and ventilation to the interior rooms. Although originally named The Astor Apartments, the building was almost immediately known only by its address, 235 West 75th Street, a possible reaction to William Astor’s unpopularity. Americans were overwhelmingly resentful of his becoming a British subject in 1899.

The Astor held 42 apartments in suites of seven to nine rooms. Annual rents ranged from $1,200 to $3,000–the most expensive equaling about $7,350 per month today. Among the residents listed in the 1901 “A Directory of the Principal Apartment Houses of New York” were some of Manhattan’s most recognizable social names, including Haight, Sanger, Kingsland, Burden, Boyd and Mabley.

Katherine M. Mabley possibly chose to move from her private home at No. 317 West 77th Street after being burglarized of more than $2,000 in jewelry in 1900. The wealthy widow summered in her cottage at Orient-Point-on-the-Sound on Long Island. Living with her were adult children, Carlton and Helene Maude.

Carlton was involved in the up-and-coming automobile industry. A principal in Smith & Mabley, he imported French automobiles like the Renaut, Peugeot and Mercedes, and manufactured cars upstate. Carlton’s name routinely appeared in newspapers for his cavalier disregard of the new auto laws.

While the family was still at the country home on September 22, 1901, the New-York Tribune reported “Carlton E. Mabley…has the distinction of being the first automobilist in Westchester County to be fined for fast riding. Mr. Mabley is one of the most noted automobile operators along the northern shore of the Sound, and owns a fast racing machine.” Mabley had been fined $25 for “running his automobile through Port Chester faster than the law allows.” (The speed limit was 8 miles per hour.)

Three months later the 23-year-old was back in jail. On December 22 he flew past mounted officer Lyon going 25 miles per hour. The New York Times reported “He mounted his horse and gave chase, and caught up with the automobilist” at 177th Street, where Mabley was arrested. “The young manufacturer protested vigorously against his arrest, but the new policeman was obdurate and took him to the station house.”

Among the residents listed in the 1901 “A Directory of the Principal Apartment Houses of New York” were some of Manhattan’s most recognizable social names, including Haight, Sanger, Kingsland, Burden, Boyd and Mabley.

Mabrey’s extensive automobile business (and his wealth) was evidenced the following August when he returned from a tour of Europe. While in France he ordered more than 300 automobiles, the total value of which exceeded $1 million. Mabrey placed the price of the more expensive models at $12,000 each — more than $350,000 today.

Nevertheless, Katherine Mabrey apparently preferred her private carriage to the new-fangled automobiles. She was in her Victoria on Saturday afternoon, October 18, 1902, headed to Riverside Drive when it was “run down” by an Amsterdam Avenue streetcar. The carriage tipped dangerously, throwing Katherine to the pavement. Her coachman, John McDonald, managed to remain in his seat and control the horses.

Katherine was less injured than her vehicle which The New York Times described as “badly damaged.” She was sent home in a hansom.

While Carlton continued to draw bad press (he was arrested again on July 5, 1903, for failing to have license plates on his car), his sister’s publicity was more respectable. Getting her name wrong, the New-York Tribune reported on March 2, 1902, that “Friends of Miss Maud Helaine Mabley…have received invitations to a ‘surprise entertainment’ on March 7. The character which the festivities will assume is known only to the hostess, Miss Mabley.”

Helene’s engagement, announced in January 1903, and her wedding to Frank M. Knight on November 4 was widely covered by society columns. Interestingly, her brother’s name was not mentioned in any of the accounts, suggesting he missed the ceremony.

Circumstances surrounding a marriage within another family in the building that year were much less conventional. George E. Double was the head of the cotton goods manufacturing firm, George E. Double & Co. The Doubles’ only child, Edna, was 24-years old and had been musically trained both in America and Europe. In 1899 she and her mother were in Saltzburg where Edna made the acquaintance of Adolph Lee Wirth of Milwaukee. Wirth was eight years older than Edna. There was an instant attraction.

The two continued their romance through letters and in 1901, the same year the Double family moved into The Astor, Wirth came back to America and “made a formal demand” for Edna’s hand in marriage. Her parents rejected the proposal and Edna later presumed “Their only reason was that I was an only child; they called me ‘the apple of their eye,’ and they did not want me to marry at all, I guess.”

Finally, in March 1903 after continuing their written romance for another two years, the lovebirds planned their elopement. Edna gave her mother her final chance to give consent, but she refused. Edna sneaked out of the apartment on March 18 and the two were married in the Little Church Around the Corner. George Double soon discovered what had happened.

While the newlyweds and two friends were having dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria, Double stormed in. Wirth fruitlessly pleaded with him not to make a scene. “Father, however, said my husband had stolen me, and he was very disagreeable, although we both begged him not to be,” said Edna later.

To escape the embarrassing incident, Adolph and Edna left the hotel and got in a cab. Double jumped into another and gave chase. The couple told their cabbie to outrun their pursuer and, as Edna told a New York Times reporter, “We were driving at a furious pace and it was a great chase. Our driver kept urging the horse on and I shouted to him ‘Go on, do your best, there is money in it for you!'”

As they entered Central Park, the cab driver made a hand signal to the other hackman. Little by little Double’s cab fell behind until the newlyweds were out of sight.

A reporter who visited the Double apartment on March 21 was told of the family’s dislike for their new son-in-law. “I did not want my daughter to marry Mr. Wirth,” said her mother, “because she was a girl much younger than her years, sensitive, of a musical disposition, and not at all suited to a man of Mr. Wirth’s caliber. I never cared for him.” The parents could not say whether the pair would be accepted in their home.

In 1913 the Astor’s owners hired the architectural firm of Peabody, Wilson & Brown to design an addition facing 76th Street. Although it rose two stories taller than the original building, the architects closely followed the Clinton & Russell design.

The unmarried Mary Belle Weeks had an apartment here at the time and would remain at least into the 1920’s. The sister of Supreme Court Justice Bartow S. Weeks, she lived on a comfortable inheritance. In the fall of 1913, she embarked on a redecorating project.

On Friday, October 8 one of the workers, wallpaper hanger Louis Hoff, suddenly complained that he was feeling ill and left. Later, as reported by The Times, “Miss Weeks found that a bag containing fifty-six pieces of jewelry, mostly heirlooms, was missing.” Mary Belle estimated their value at $37,700 by today’s standards.

She received a shocking telephone call four days later. It was Louis Hoff, who said he had become “conscience stricken” and decided to return the stolen items. He told Mary Belle that if she “would meet him at Seventy-fifth Street and Broadway he would return the jewelry.” She agreed, then notified Detective McCarton who had been working on the case.

Mary Belle Weeks got her family pieces back and the conscience-stricken paperhanger was sent to jail.

In 1926 the Winant family moved into the Astor Apartments. William Alfred Winant and his wife, the former Margaret (known as Maggie) Frances Overbaugh, had two grown children, Marguerite, who moved in with them, and William, Jr. Winant was a principal with August C. Lockwood, in the seafood business Lockwood & Winant in the Fulton Market. Maggie had attended the Rutgers Female Institute and College and was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Daughters of 1812.

The Winants only occasionally appeared in the society columns; one exception being the June 8, 1930 dinner given in their honor by Marguerite and William to celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary. But press coverage of William Sr. the following year was less complimentary.

“I did not want my daughter to marry Mr. Wirth,” said her mother, “because she was a girl much younger than her years, sensitive, of a musical disposition, and not at all suited to a man of Mr. Wirth’s caliber. I never cared for him.”

The Fulton Fish Market had been taken over by the mob. In 1931 a Senate investigation looked into what was called “a vast market racket” and on April 9 William Alfred Winant was called to testify. Whether he was concerned about retaliation or was personally involved in the shady dealings is unclear, but his testimony praised the alleged gangsters.

The New York Times reported “He has been in the fish business for forty years, he said, and conditions were never better in the market than they are now under the beneficent rule of Lanza and Skillin.” The article said he “left little doubt in the minds of those who heard his testimony that he was opposed to any official interference with the status quo in Fulton Market.”

He did admit, however, that after a union labor contract had been negotiated a year earlier, “his concerned received notice of an assessment for ‘expense of the labor committee.'” The $700 assessment would be more than $10,000 today.

The Winants were still living in The Astor in 1941 when they celebrated their 60th anniversary. William was by then the president of the Fulton Market Association. But they would have to move out by 1944.

Turn of the century apartment buildings had fallen from favor by now. Newer buildings with modern amenities pushed the old structures into obsolescence. In 1944 The Astor was converted to a single room occupancy hotel called the West Side Towers, with nine stores now carved into the street level.

On April 1954 an 18-year-old girl, Josephine Carrion, attended an all-night party in the room occupied by sailors Dwain Lattimore and Wilbur Watson. At some point things turned ugly and another guest, 25-year-old ex-convict James Futrell shot her. He and several other of the partiers dragged her out onto the sidewalk and fled. She was found dying there at around 4 a.m.

The grisly murder was only a hint of what was to come. In 1972 the building had drawn the attention of Attorney General Louis J. Lefkowitz. On December 15 The New York Times reported that he listed among neighbors’ complaints paper bags of human excrement and urine thrown from windows and hitting passersby below; drug deals done openly on the sidewalk and in the halls; “pimps and prostitutes [who] accost passersby practically 24 hours a day;” and knifings and clubbings that take place “every day.”

A January 1973 court order demanded that the owners “rid the hotel of criminal elements.” Nothing had improved by August 3 when The New York Times reported “The managers of the West Side Towers, a single-room-occupancy hotel, were pictured as the ‘Fagins in a chamber of horrors, spreading sickness, death and despair’ among community residents, in court papers filed against the owners and operators by Attorney General Louis J. Lefkowitz.”

Lefkowitz had received 39 affidavits that said “the hotel managers had operated as receivers of stolen merchandise, made loans at usurious rates, withheld funds rightfully belonging to tenants, forged signatures on welfare checks and, in some cases, delayed reporting the deaths of welfare recipients until their checks arrived and could be cashed.” The building was still the haunt of prostitutes, pimps and drug dealers, as well.

Change finally came in December 1977 when a conversion to 220 studio and one-bedroom apartments was announced. Owner-builder Herbert Mandel had been rehabilitating properties for over a decade. He promised a “100 percent gut renovation” while preserving the exterior appearance.

Mandel rechristened the renovated building The Astor. The real estate brochure called it “a stately reminder of New York’s splendid past which cannot be duplicated today” and boasted “Hollywood kitchens” and Venetian blinds on all windows. The building once decried as a “chamber of horrors” emerged once again as a reputable and handsome place to live.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 2141-2149 Broadway:

Meet Aaron Dussair!