The Hotel Prisament

by Tom Miller

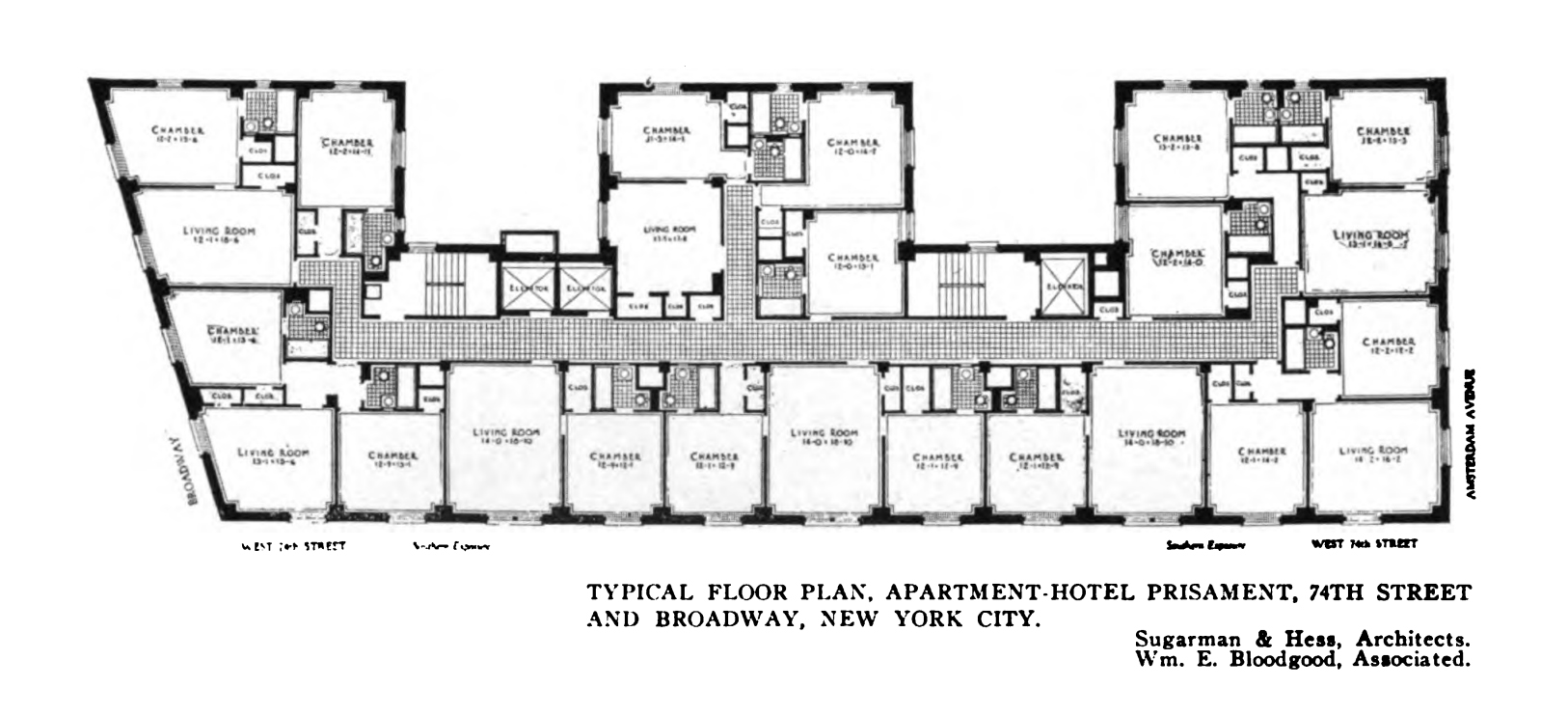

In 1921 Joseph Zuber assembled a syndicate called the 2120 Broadway Corporation to construct a sprawling residential hotel facing West 74th Street, stretching from Broadway to Amsterdam Avenue. The firm of Sugarman & Hess designed the 15-story in a subdued take on the Italian Renaissance style. Completed in the fall of the following year, its three-story stone base held stores on Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue, while the residential entrance on West 74th Street sat within an overblown Renaissance-inspired, double-height frame with fluted pilasters that upheld a massive broken pediment. The structure cost $1 million to construct, or about 16.2 million in 2022 dollars.

As the building rose, in January 1922 the 2120 Broadway Corporation leased it to Theodore and Paul Prisament, who did business as Prisament Brothers. They operated the Alcazar Hotel in New York and a small hotel in Washington D.C. Their Hotel Prisament opened on September 27, 1922, with a total of 336 rooms. Like all residential hotels, the apartments had no kitchens, but rather residents had the option of taking their meals in an upscale restaurant-like dining room.

The New-York Tribune reported, “Ten years ago two boys from Constantinople entered America with just enough money to get them safely past Ellis Island. Last night the same two, Paul and Theodore Prisament entertained 500 of their friends at the opening of their new Prisament Hotel.” Theodore told a reporter, “We always planned that we would operate such a place someday, and now our dream has come true.” There was nothing magic about our success. We worked morning, noon and night and all with just the one purpose.”

The apartments filled with affluent, professional families, like the William S. Bakers. On July 29, 1924, the society page of The New York Times reported that “Mr. and Mrs. William S. Baker of the Hotel Prisament…announced the engagement of their daughter Sylvia to Mr. Joe Harris of New York.” And the following year, on December 9, the newspaper reported on the wedding of the Bakers’ son Arthur in the ballroom of the Hotel Astor.

“Ten years ago two boys from Constantinople entered America with just enough money to get them safely past Ellis Island…”

A less formal engagement was announced in the apartment of novelties manufacturer Irving Wheeler that same year. Wheeler provided financial backing to the Broadway show, Plain Jane at the Elting Theatre. In August 1924, a 15-year-old girl, Muriel Dawn, auditioned for a part and was introduced to him. The New York Times later reported, “She says he gave her a job and later became attentive to her, and finally at a dinner at his apartment in the Hotel Prisament, he announced their engagement.”

The slick-talking Wheeler, it seems, had no intention of marrying the teen, but merely wanted to become intimate. Two years later, on August 25, Muriel took Wheeler to court. Because she was just 17, her married sister had to file the action in Supreme Court on her behalf. She sued Wheeler for $75,000 damages for breach of promise. The substantial amount would top $1 million in 2022. The New York Times reported, “Wheeler will file a denial of the allegations, it is said.”

The affluence of the residents was reflected in the burglary of the Philip Stein apartment on June 9, 1927. The Steins went to the theater that night, and when they came home Mrs. Stein discovered that $10,000 worth of jewelry had disappeared.

A similar incident occurred in the apartment of Mrs. Rebecca Jones the following year, however she was unlucky enough to walk in on the thugs. The 59-year-old widow returned to her fifth-floor suite around 10:00 on the night of January 9, 1928. When she flicked the light switch, it did not work. She felt her way from room to room, trying the lights. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported, “As she groped her way out of the bedroom, two men seized her, one throwing a towel over her face and the other hurling her to the floor. She was bound and gagged with adhesive tape over her mouth.”

The bandits had already bagged up about $8,000 in jewelry, but they now pulled three diamond rings off Mrs. Jones’s fingers—one of which was her engagement ring. The newspaper said she valued the rings at $6,000. Luckily, she told police, “she had been in the habit of wearing two bracelets worth $15,000 in addition to her rings, but recently placed them in a safe deposit box.” Because there were no lights and her head was covered, she was unable to give a description of the men.

The wealthy permanent residents of the hotel were doubtlessly unaware that some of their transient neighbors were criminals of the most depraved type. On the morning of July 13, 1928, police raided an apartment and arrested five men. The Yonkers Statesmen reported that they “were held for questioning in connection with the recent murder of Frankie Yale, Brooklyn underworld king.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted that one of the men, 29-year-old Moe Liss, was also wanted in Los Angeles “in connection with the hold-up and murder of a paymaster near Los Angeles on April 26, 1927,” and was sought for questioning regarding the shooting of a narcotics agent in the West. The Yonkers Statesman added, “A quantity of opium was also seized, police announced.”

On May 2, 1928, a Chicago newlywed couple, George and Rae Sleschman, took rooms on the second floor. They had been married 10 months earlier. While her husband was busy downtown on May 4, Rae took the elevator to the 12th floor. Construction workers on a nearby building noticed the 22-year-old loitering around a window for about half an hour, before climbing onto the sill and jumping. Her identity was a mystery until George Sleschman returned to the suite and could not find his wife. The New York Times reported, “Her body was identified at the West Sixty-eighth Street Station early last night by her husband, who was prostrated at her death.”

Around 1929 the Hotel Kimberly Company purchased and renamed the building. The days of wealthy, respectable residents had come to an end, and the Hotel Kimberly became a favorite among gangsters and petty criminals. Living here in 1931 was 31-year-old John J. Philips, alias, Harry Fox, aka “The Jumper.” On October 31 that year, he aimed a high-powered weapon out of his third-floor rooms and shot Joseph Brody, the owner of a cordial shop, dead. Following his arrest, on November 20 The Philadelphia Inquirer reported, “New York police believe the killing resulted from an attempt of a Philadelphia cordial syndicate to extend its activities to New York.”

Earlier that year an aspiring actress and model from Jamestown, New York took a room with her best friend, Marion Strong. Lucille Ball would become, of course, one of America’s best-known actresses and comediennes. But for now, she was a struggling single girl in a big city. According to her biographer Barry Monush in his 2011 Lucille Ball FAQ, she and Marion rented room 712, “sleeping in twin beds and sharing a bureau for eighteen dollars a week.” He writes, “Lucille later claimed that while she was living at the Hotel Kimberly, a gang war broke out in the neighborhood and, while she was taking a bath, a bullet hit the tub and drained all the water.”

Earlier that year an aspiring actress and model from Jamestown, New York took a room with her best friend, Marion Strong.

The names of residents of the Hotel Kimberly continued to appear in newspapers for the wrong reasons. On July 1, 1935, The New York Sun reported that the body of Joseph Goodglass had been retrieved from the Long Island Sound. “The body was found trussed up with ropes,” said the article. He was identified by his tattoos. The medical examiner said, “the man had apparently been murdered by a blow on the head and the body then thrown into the water.”

In December 1938, another Kimberly Hotel resident, Clayton J. Morse, was arrested for mail fraud. On January 5, 1939, The Sun reported that he “is said to be suffering from extreme depression brought on by his pending trial.” The day before he had threatened “to murder several persons, including Mr. Fennelly himself.” Leo Fennelly was the Assistant United States Attorney. Upon being told of the threats, Fennelly ordered that Morse be taken to Bellevue Hospital for observation. In the end, Morse’s trial would never come to a decision. About 25 minutes after midnight on February 8, his wife walked into their Kimberly Hotel apartment to find her husband’s lifeless body hanging from the ceiling.

A renovation completed in 1950 resulted in 16 apartments per floor throughout the building. By 1970 it was owned and operated by the city as a welfare hotel. On November 26, 1972, The New York Times reported that the Kimberly Hotel was a “source of crime, according to the police.” The article quoted officers as saying it is “’heavy in junk.’ And they report that it attracts many outsiders who feel they can easily purchase heroin or other drugs there.” Some of those “outsiders” entered the building to buy drugs, only to be mugged and have their money stolen. “Back on the street, they can hardly complain to the police,” said the article.

In 1975 the building was converted to the Lincoln Square Home for Adults, a residence for the elderly. It was sold—under heated protest from the residents themselves and public advocates—in 1984. The subsequent remodeling resulted in The Fitzgerald, residential condominiums. An advertisement in New York Magazine in 1987 left no hint of its many former incarnations. “The Fitzgerald offers marble baths, a 24-hour concierge attended lobby, a common rooftop garden sundeck.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the local businesses at 2120-2122 Broadway aka 300-302 Amsterdam Avenue aka 201-203 West 74th Street:

Meet Chris Rudney!