The Ansonia Hotel

by Tom Miller

Strolling along upper Grand Boulevard (which would be renamed Broadway) in 1895, William Earl Dodge Stokes had a vision: he imagined Broadway as a wide fashionable boulevard similar to the Champs-Elysées in Paris. Over the course of the next few years he bought the property on the site of the former New York Orphan Asylum between 73rd and 74th Streets.

Here he planned for a grand French residential hotel. But not just any hotel. This would be the largest, the costliest and the most ornate; and its location at the bend in Broadway would make it visible for blocks.

It would be named The Ansonia. (The name came either from his grandfather, Anson Phelps; or from Phelps’ firm The Ansonia Clock Company; or from the town where the factory was located: Ansonia, Connecticut.)

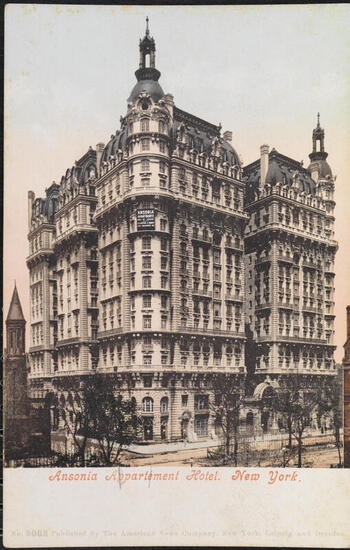

Stokes contracted the French architect Paul E.M. Duboy, who had studied at the École des Beaux-Arts, to design the building. Duboy used Parisian Beaux Arts apartment buildings as inspiration, however the Ansonia would be three times the size. Seventeen stories tall with foaming ornamentation, a curved mansard roof with corner turrets topped with enormous copper lanterns, it was hyperbole in steel and stone. Everything was the most or the biggest.

With over half a million square feet, there were 1,400 rooms and 340 suites. Residents would have the use of the ballroom, several cafes and tea rooms, dining rooms, a Turkish bath, writing rooms, the largest indoor swimming pool in the world and, unbelievably, a lobby fountain with live seals. Joseph Gill-Martin, hired as the building’s curator, purchased over 600 oil paintings to decorate the interior.

William Stokes demanded so much input regarding the layout of the floorplan — insisting on oval and other eccentrically shaped rooms — that he finally paid the frustrated Duboy $5,000 to go home to Paris. Duboy did — where he promptly suffered a nervous breakdown.

Ground was broken in 1899 and construction lasted five years. The result was a sumptuous pile, its great bulk broken up by the over-the-top ornamentation, balconies, and irregular surfaces. The Ansonia opened for business in 1904. Its tiers of lavish decoration quickly earned its nickname “The Wedding Cake of the Westside.”

Seventeen stories tall with foaming ornamentation, a curved mansard roof with corner turrets topped with enormous copper lanterns, it was hyperbole in steel and stone.

The residents would not want for much. In the summer, frigid salt water was piped through the walls to keep the apartments at a constant 70 degrees. An ingenious pneumatic tube system connected apartments with the staff so messages could be whisked back and forth. The Persian carpets in the suites were custom woven and there were stained glass windows. Three times a day a maid would replace the towels, soap, table linens and stationery in each suite. A wide white marble staircase with a Beaux Arts iron and mahogany bannister spiraled down all seventeen floors. For those occupants who had no intention of cooking for themselves there were apartments with no kitchens.

And for those who did cook, there was a small menagerie on the roof consisting of over 500 chickens, some ducks, and goats. Every morning a porter would deliver fresh eggs to the tenants. Every morning until 1907, that is, when the Health Department put the end to the rooftop farm.

The problem with the Ansonia was its location. It was on the West Side and no amount of luxurious amenities could change that. Instead of barons of industry and the social elite, the apartment lured athletes and small-time criminals. Babe Ruth lived here and considered the entire building home – often wearing his slippers and robe to the lobby to get a shave. Yankee players Wally Schang, Lefty O’Doul, and Bob Meusel also lived there along with boxer Jack Dempsey.

Here the 1919 World Series was fixed when a group of White Sox players agreed to throw the game for $10,000 per man. Gangster Al Adams lived at the Ansonia for two years before badgering from law enforcement drove him to suicide in his suite.

Entertainment personalities and musicians also called the Ansonia home attracted, for one thing, by the double-wide doors (installed in all apartments so as to accommodate a grand piano) and by the thick masonry walls throughout that guaranteed sound-proof rooms.

Flo Zeigfield lived here with his wife while his mistress lived a few floors below. Conductor Arturo Toscanini and his family moved in as well as scores of opera stars. Rachmaninoff, Mahler, and Stravinsky had apartments here and, for three decades starting in the 1920’s, Wagnerian tenor Lauritz Melchoir lived here, using the long hallways for archery practice.

In 1926 Stokes died, leaving the Ansonia to his son who was unenthusiastic about it at best. He left its management to third-party companies and little by little the upkeep of the building was neglected. The Depression hit the Ansonia hard. The dining rooms closed. Services were discontinued. The grand main entrance was plastered over and mismatched storefronts intruded into the street level facade.

With the advent of World War II, the management stripped the building of “excess” metals for the war effort. Tons of copper, including the decorative lanterns on the turrets were removed. The cold salt water piping in the walls was torn out as was the pneumatic tube system.

And things just kept getting worse.

The building was sold in 1945 to Samuel Broxmeyer. An unscrupulous crook, Broxmeyer bargained with the tenants, offering them large discounts if they would pay their rent several years in advance. He then disappeared. Broxmeyer ended up in prison and the Ansonia sold for $40,000 at a bankruptcy auction.

Jacob Starr, the new owner, soon realized that his $40,000 investment was going to cost him millions in needed repairs and updating to bring the old building up to code. He decided, therefore, to do nothing. As the 1960’s approached the structure was in decrepit shape. The roof had multiple leaks. Pipes corroded. The ornate balconies were rusting away.

In order to generate added revenue, Starr rented the old Turkish bath and swimming pool area to The Continental Baths in 1968. Not a mundane gay bathhouse, it featured palms, a cascading waterfall into the pool, a disco and a clever system of colored lights that tipped off patrons of approaching police.

And it had a cabaret.

Here aspiring entertainers performed for towel-clad young men. As the word spread, husbands and wives straight from dinner on the town stood in line to see the show. “Bathhouse Bette” was a favorite among the crowd. She later became known as Bette Midler. Her pianist, Barry Manilow, would sometimes play in a towel just to fit in. Squeaky-clean John Davidson performed here early in his career as did Melba Moore and Peter Allen.

“The hotel’s architectural appearance is not worthy of designation of a landmark. I am not, nor is the owner, aware of any particular historic significance to the building.”

None of this helped the situation on the floors above. In 1968 the tenant’s association won a decision from the courts to freeze rents until repairs were made on the building. Starr had a better idea. He would tear the Ansonia down and build a 40-story modern apartment building.

Refusing to cave in, the tenants sought support from the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Starr was incensed. He told one resident “I have the most powerful men in Washington representing me.” When the Landmarks Preservation Commission held its first hearing in April 1970, Starr’s lawyer flatly stated “The hotel’s architectural appearance is not worthy of designation of a landmark. I am not, nor is the owner, aware of any particular historic significance to the building.”

The testimony sparked demonstrations and a petition, signed by over 25,000, requesting Mayor John Lindsay to save the Ansonia. The residents, many of whom were from the entertainment industry, had 73rd Street closed for a free five-hour fund-raising and public awareness concert. A few months later the exterior of the Ansonia was designated a landmark.

Defiant, Starr refused to spend anything on the maintenance of the interior. Life for the residents continued to get harsher.

The Continental Baths moved out in 1977 and Starr replaced it with Plato’s Retreat — an unabashed sex club where couples paid an entrance “membership fee” of $30 for a night of debauchery. A sex shop opened on street level and men loitered around the building. But before Plato’s opened, Jacob Starr had died.

His grandchildren inherited the Ansonia; however his will strictly stipulated that his money, which was left in trust, was forbidden to be used for upkeep of the building. Jacob Starr died a very angry man.

Jesse Krasnow purchased the dowager building in 1978 and immediately took out $21 million in mortgages to be used for stabilizing and restoring the facade and for interior improvements. He told The New York Times “The halls were yellow. Dreary. Discolored linoleum, fluorescent lights, bare bulbs, and old tiles.”

In 1990 the tenants accepted a condominium plan. Restoration and improvements continue, with Krasnow having put over $100 million into the old “wedding cake.” The Ansonia has been through some hard times but she still stands proudly at the bend of Broadway at 72nd Street.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Landmarks Timeline

Keep Exploring

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses currently at 2101-2119 Broadway, and read more about this landmark from our partners at the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project!:

Meet Byung Lee!

Meet Demetrios Mitsopoulos!

Meet Ashley Jaffe and Zach Israel!

Continental Baths at

the Ansonia Hotel

Meet Ken Lustbader!