Lester Building

by Tom Miller

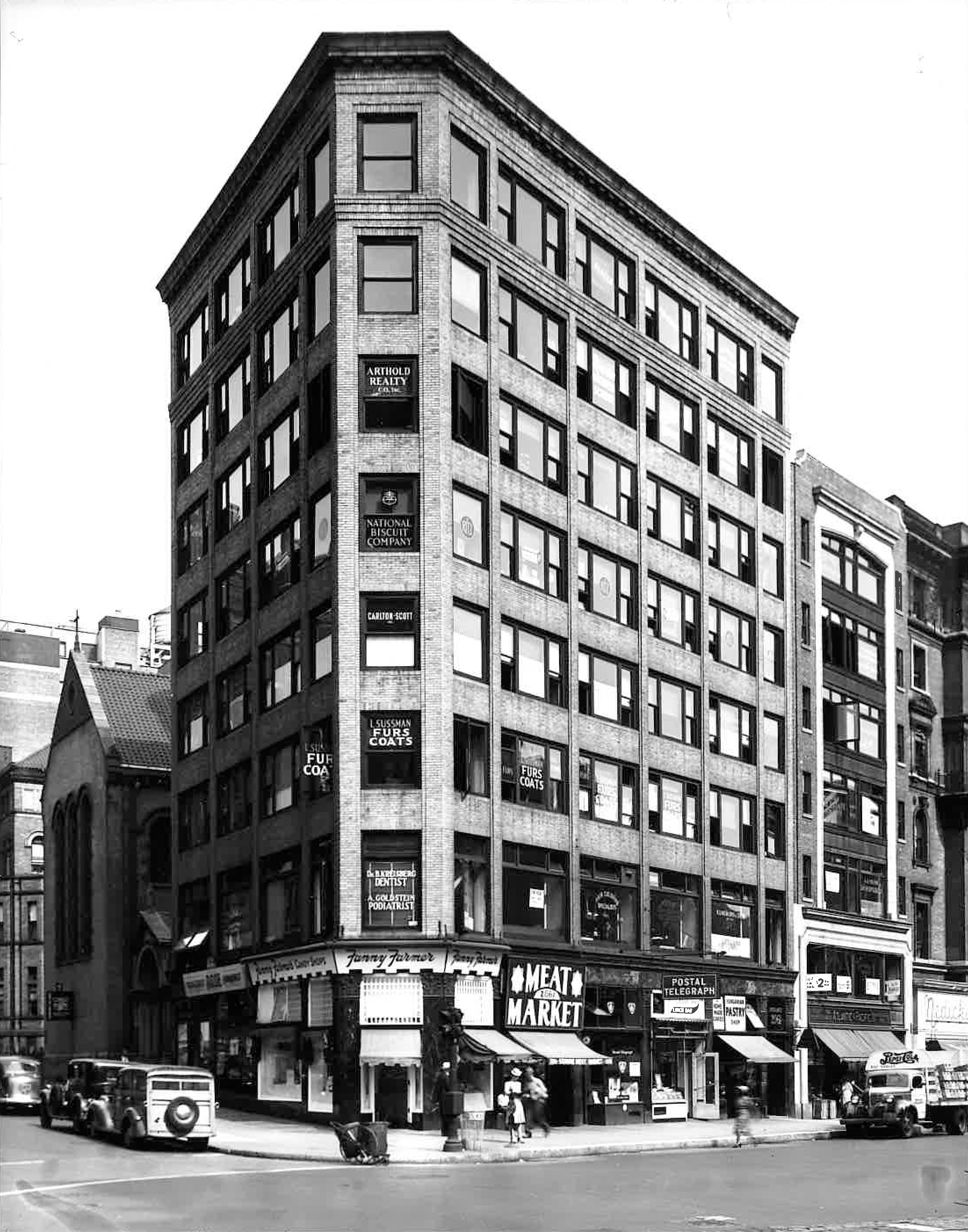

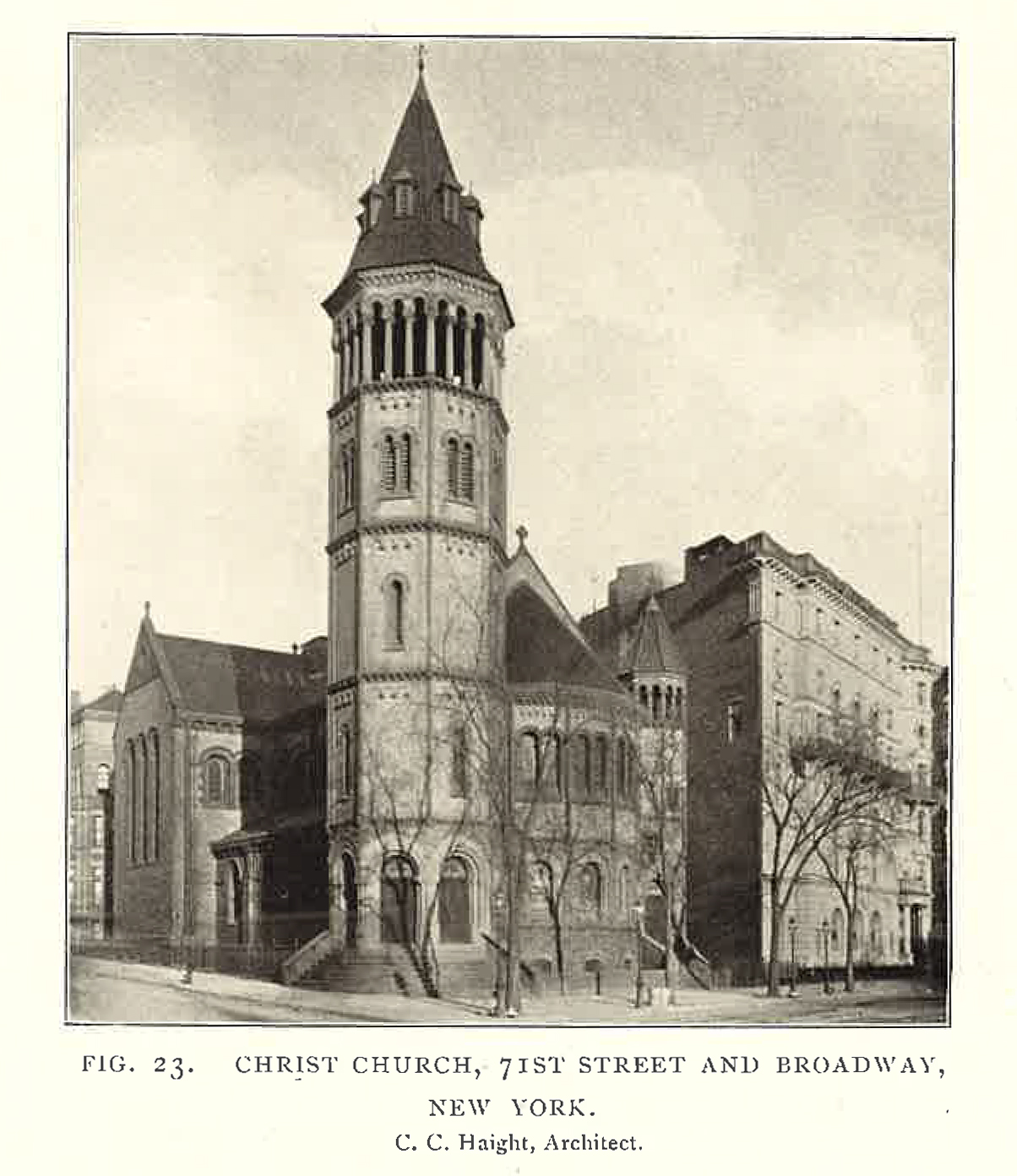

In 1923 the Lester Building on the was completed on the northwest corner of Broadway and West 71st Street. The architectural firm of Very, Browy & Behr had designed the eight-story structure in the Chicago Style, sometimes called the Commercial Style. Faced in beige Roman brick, its most eye-catching elements were its chamfered corner, and the Chicago windows, nearly obligatory to the style. Retail shops occupied the sidewalk level and the interior mezzanine. The upper floors held ten office spaces each.

Only three years after its completion, the building’s owner, the 2069 Broadway Corp., did minor renovations. It was possibly at this time that a veneer of heavily veined, polished black stone was applied to the storefronts. The remodeling brought in a rush of new tenants. Signing office leases that year were the Greater Pythian Temple Association, the Automotive Electric Service Company, the New York Philanthropic League in Aid of Crippled Children, and the real estate offices of Edward Rose. In the building at the time, as well, was the Vaporetter Products Company, which manufactured “fuel vaporizing and economizing devices,”

“Because of exorbitant rentals and unsanitary living conditions, 24 Negro families declared a rent strike today against the New York Lease Co., 2061 Broadway. A continuous picket line was thrown in front of the building.”

The ground floor was shared by two tenants in the Depression years: the women’s apparel store of Jeanette Braunstein and O’Connor’s Tavern. The building had been a favorite of real estate offices over the years, and by the mid-1930’s the New York Lease Co. had moved in. The firm’s questionable—even racist—practices triggered a backlash in the fall of 1937.

On September 16, the Daily Worker reported, “Because of exorbitant rentals and unsanitary living conditions, 24 Negro families declared a rent strike today against the New York Lease Co., 2061 Broadway. A continuous picket line was thrown in front of the building.”

The chairperson of the strike committee, Mrs. Anita Towers, explained, “The apartments have not been decorated for years. In many rooms there are holes a foot wide in the ceilings and floors. The landlord is demanding for these slum apartments a 30 per cent increase in rentals.” The Daily Worker expounded, “The apartments are ill ventilated; in many rooms there is no fresh air or sunlight at all. On wash days the areas are so crowded with clothes hung out to dry that a child cannot see the sun from where he is forced to play.”

In response to the rent strike, the New York Lease Co. simply sent eviction notices to the non-paying tenants. One of them told a Daily Worker reporter, “If he carries one of us to court for non-payment of rent, then he will have to carry us all.”

Ironically, given the precedence set by the New York Lease Co., in the 1970’s the Panel of Americans was leasing space in the building. Founded in California in 1946, it was originally formed to help Mexican workers who faced discrimination and the Japanese Americans who had been interned in that state. Now, from its rooms in the Lester Building, it worked with a wide swath of New Yorkers—Pakistani, Puerto Rican, Black, Asian, Mexican, and others.

As had been the case with The New York Lease Co., the Sensational Real Estate office was accused of racial discrimination in renting apartments in 1977. The Opening Housing Center of the New York Urban League examined the charges as part of an ongoing investigation into widespread racial discrimination in Manhattan apartment rentals. Happily, broker Donald M. Heinz and his salesperson, Brian McDevitt, were both cleared of any wrongdoing.

Born in Warta, Poland, the son of a watchmaker, he spent years of his youth in a total of 21 Nazi concentration camps and prisons.

Two years after that incident, in 1979, the upper floors were converted to residential spaces—one apartment per floor. That year the ground floor was occupied by the Fulton Café and William Landau’s jewelry store. Laundau had had a tumultuous journey to get here. Born in Warta, Poland, the son of a watchmaker, he spent years of his youth in a total of 21 Nazi concentration camps and prisons. He kept himself alive by being able to fix the watches and jewelry of the guards. He told Francis X. Clines of The New York Times in April 1979 about “a 48-hour march in Silesia with no food, when he stayed up and moved forward because those who dropped around him were shot on the spot.” He managed to survive until Allied troops freed the camp survivors. Unfortunately, nearly all of William Landau’s family had perished. “The Germans’ war destroyed 67 of the 71 Landaus of Warta,” he said.

In 1986 the ground floor was taken over by a Manufacturers’ Hanover Trust bank branch. Today it has been divided into three commercial spaces. Overall, Very, Browy & Behr’s somewhat rare example of the Chicago Style in Manhattan is nearly unchanged since 1926.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the local businesses at 2061-2065 Broadway: