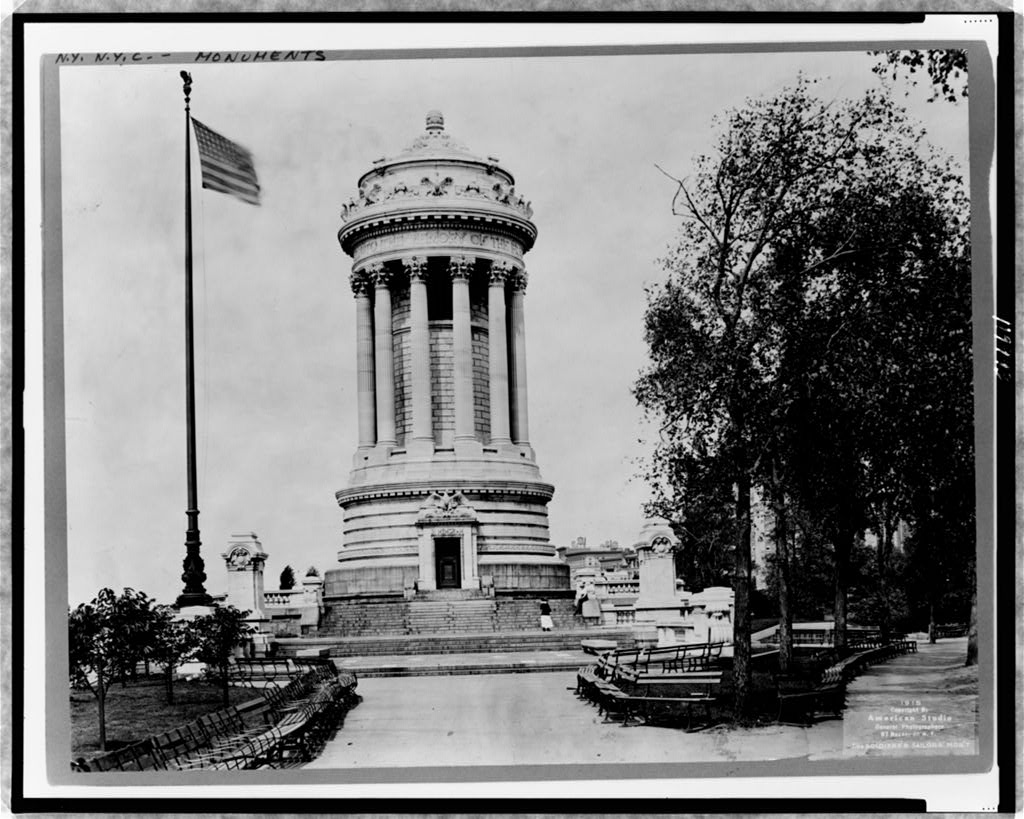

The Soldiers’ & Sailors’ Monument

by Tom Miller

In 1869, five years after the end of the Civil War and acting on requests of the Central Park Commissioners, the New York State Legislature approved the erection of a Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument. A decade later, on May 22, 1879 nothing had been accomplished. Five prominent New Yorkers wrote an open letter, published a week later in The New York Times, hoping to kick-start the project.

The group, composed of General H. W. Slocum, Levi P. Morton, John R. Brady, Lloyd Aspinwall, James McQuade, John T. Hoffman and E. D. Morgan, proposed the formation of a “Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument Association.” Its purpose would be to “undertake to erect a suitable monument in this City to commemorate the services of the Union soldiers and sailors of the late war of the rebellion.”

It was a commendable move. But the gentlemen would have a long wait.

Four years later still little had been done and, as a matter of fact, the committee lost two of its most prestigious members—Judge John T. Hoffman and General H. W. Slocum had resigned. General Slocum stepped down “based on the ground that as the citizens of Brooklyn were endeavoring to erect a soldiers and sailors’ monument, he thought his services properly belonged there,” reported The New York Times on March 29, 1883.

By 1894, Civil War memorials had been erected throughout the country. Even small towns had prominent monuments to its servicemen. Brooklyn’s magnificent Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Arch had been dedicated in 1892. But the Manhattan memorial was still mired in squabbles over its design and location. When the Albany Legislature appropriated money for the project, it called it “the Memorial Arch.” And the Legislature neglected to earmark funds for the “preliminary expenses,” like notices to sculptors and architects and the conducting of a competition.

“That omission caused the project to fall into oblivion, until it as recently recalled by a gentleman interested in the adornment of the city who has no axe to grind, but happens to be a member of the Sculpture Society,” reported The Times on January 7, 1894.

The Sculpture Society, the Architectural League and the municipal Art Society joined forces to get the monument back on track. And the first thing they dealt with was the “Memorial Arch” designation. The Commissioners of Parks announced that there was no place in Central Park for an arch. Various locations for a triumphal arch were suggested. The two favorites were the intersection of Broadway and Fifth Avenue at 23rd Street; and the sea wall of the Battery near the New York Aquarium. A newspaper noted “With a flight of steps leading to it from the water, it would furnish a splendid point of departure for processions in which naval brigades figure or companies of soldiers arriving in the city by water.”

But the Manhattan memorial was still mired in squabbles over its design and location.

Almost two years later, there had been no decisions and no progress. Many New Yorkers pushed for a monumental arch at the entrance of Central Park, on the Fifth Avenue plaza. But the Fine Arts Federation fought back, saying it “is a very bad site for a monument, especially for a lofty monument such as the committee has decided to erect.” The Federation firmly felt that the monument should be “placed at some point of the water front, where it will be visible from water as well as from the land.”

A new location had recently been proposed—Riverside Drive. The Times noted on December 15, 1895, “At one end of the drive Grant’s tomb is already rising. If the other end were bounded by a military and naval monument visible from afar and easily accessible from close at hand…the border of the drive between these two terminal monuments would become the fitting repository of the monuments of individual military and naval heroes.”

The committee was back to square one in June 1896. Following a meeting with the Mayor on June 10, Madison Square was again the front-runner. The “small triangular block bounded by Broadway, Fifth Avenue, and Twenty-Second Street” (the future site of the Flatiron Building) was deemed “advantageous.” Newspaper readers were told that the 59th Street plaza at Central Park was now ruled out; and Riverside Drive had been deemed “out of the way.”

To the surprise of most New Yorkers and despite the vehement opposition of military and arts groups, on July 17, 1897 the Mayor and the Parks Commissioners announced their choice of locations—the Central Park plaza at Fifth Avenue and 59th Street. The New York Times was clear in its opinion. “The thing is absurd and monstrous, and it is greatly to be hoped that the commission may yet show itself disposed to listen to reason.”

The public was quick to respond and on July 18 a Civil War veteran William Henry Shelton, added his opinion to the letters arriving on the desk of the editor of The New York Times. After pointing out that the old servicemen were getting on in years, he presented an eloquent case for Riverside Drive. His letter said in park “The winding course of the stately avenue, with its many hills and knolls and great, sloping lawns, will lend itself to monumental treatment on a great scale.”

Later that year, at last, on October 16, 1897, the six architectural submissions for the monument were displayed in the Central Park Arsenal. Surprisingly, only one was an arch. The others were soaring columns adorned with sculpture—highly similar to the Columbus monument erected at the Columbus Circle entrance to Central Park five years earlier. On November 12, the winning design was announced—the 125-foot column on a terraced pedestal by brothers Arthur A. and Charles W. Stoughton. The sculptures would be executed by Frederick MacMonnies and it would be placed at the 59th Street entrance to Central Park; a near-matching bookend to the Columbus shaft.

Almost immediately, however, John Quincy Adams Ward, President of the National Sculpture Society, blocked the project. By law no monument could be erected on land belonging to the City of New York without the sanction of the National Sculpture Society president. And Ward refused to approve the plaza location. “It is, therefore, evident that the proposed monument cannot be put on the Plaza while Mr. Ward lives,” reported The New York Times on November 24.

And so everyone went back to the drawing board.

Ward, the Civil War veterans, and the artistic societies got their way when a month later the Riverside Drive site was approved. But now another problem arose—the shaft design of the monument.

The heroic column was not appropriate for the new location. Civil War General Rush C. Hawkins made his opinion known in a letter on April 13, 1898. He said in part that the committee that selected the design “proves that its members were quite incapable of discriminating between the truly artistic and the commonplace of the period meretricious…The design is so inharmonious and trifling in its relation to suggestion of heroic deeds, and generally so much like a piece of ornate window confectionery in its sculptural details, as to render it entirely unfit for the expression of the object intended. In short, it is quite devoid of nobility of form and expression, and has none of that solemn grandeur of outline which the events it ought to commemorate and express demand.”

The General called the $250,000 set aside for the monument a “vicious waste of good money” and hoped “some authority” would “prevent the erection of this monument in a city already too much afflicted with bad statues and hideous monuments.”

William Rudolf O’Donovan added his opinion on New Year’s Day, 1900. He said after a serious of misfortunes that had changed the location six times, “the condition seems worse now than ever before.” While the Riverside Drive site was considered “a good one” by landscape experts, it was not right “for the approved design which was made for another place.” O’Donovan felt that erecting the Stoughtons’ shaft would end in “perpetual evidence of the neglectfulness or incompetency of the Municipal Art Commission.”

Rather surprisingly, the commission paid attention. Arthur and Charles Stoughton were sent back to the drawing board. With French architect Paul Emile Marle Duboy, they came up with a vastly different monument: a white marble structure based on the ancient Choragic Monument of Lysicrates near the Acropolis in Athens. The classic building would stand on a circular plaza girded by marble walls and balustrades. The interior was lit by an oculus within a mosaic-decorated rotunda.

On December 15, 1900—more than three decades after the project began—the cornerstone of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument was laid by then-Governor Theodore Roosevelt. More than 1,000 Civil War veterans were there. General Albert D. Shaw said in part, “The monuments we raise to our Union heroes are not memorials of conquest.” The soldiers, he said, “faced death for a cause they held dear, and died like brave men in the defense of what they believed to be their precious rights.”

The General called the $250,000 set aside for the monument a “vicious waste of good money” and hoped “some authority” would “prevent the erection of this monument in a city already too much afflicted with bad statues and hideous monuments.”

The monument was dedicated on Memorial Day 1902. A procession of veterans, 2,000 schoolchildren and other dignitaries marched from Fifth Avenue and 47th Street to the site. Old soldiers carried the flag that waved over the cutter McClelland in New Orleans on January 29, 1861, which prompted Major General John A. Dix to order “If any one attempts to haul down the American flag, shoot him on the spot.”

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument was the focal point of Memorial Day observations for decades to come. But civic monuments and statues were plagued by neglect and a lack of funds to maintain them. Only five years after the monument was dedicated, it was in horrific condition.

On March 26, 1907, Mayor George McClellan held a hearing on a bill introduced by Senator Saxe at Albany to appropriate $20,000 for repairing the monument. A committee of veterans urged him to sign the bill. The New York Times reported that the structure “is in such bad repair that there is danger of some of the marble slabs falling from their places and being broken on the floor below. Three slabs have already been broken.”

One veteran, Dennis Farrell, reported that “The interior of the monument had sweated, causing a disintegration of the cement between the marble slabs.” He told the Mayor that pieces of masonry were “continually falling from the walls and ceiling.” On the floor inside the monument, were pools of water that dripped from the dome.

Following World War I sculptor Salvatore E. Florio was commissioned to add a bronze panel to the door of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument. The base relief work, about two by three feet, was a tribute “to the men who died overseas” and included the inscription “A Donation to My Comrades—To those who live beyond, our hearts offer tribune, as our memory of their sacrifice grows ever vivid in esteem and love. Humanity will remember the heroes who fought for Democracy and Justice.”

Not everyone felt so patriotic, however. On June 24, 1922 someone noticed that the bronze plaque had been stolen—no doubt for its scrap value. Officials said, “When it was stolen is not known.”

And by 1939 the Stoughtons’ classic monument had fallen from critical favor. The Works Progress Administration’s New York City Guide described it saying, “The monument, more sculpture than architecture to many, lacks the clarity of form and simplicity of some of the better American memorials.”

The once-glorious white marble monument did not fare any better during the next seven decades. By 2015, the interior space had been locked for years for safety reasons. The few city officials who entered were required to wear hard hats to protect themselves from falling masonry. The Riverside Park Conservancy hoped to raise $50,000 that year to study the deterioration and necessary repairs. As had been the case in 1907, pools of water stood on the floor inside and the walls were water stained and crumbling.

Civic memory, it has been said, is short. The marble monument to Civil War veterans which took so many decades to complete sits humiliated and decaying on Riverside Drive. While preservationists scramble to discover the extent of the damage and plot a restoration; the memorial remains a shameful testament to civic indifference.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com