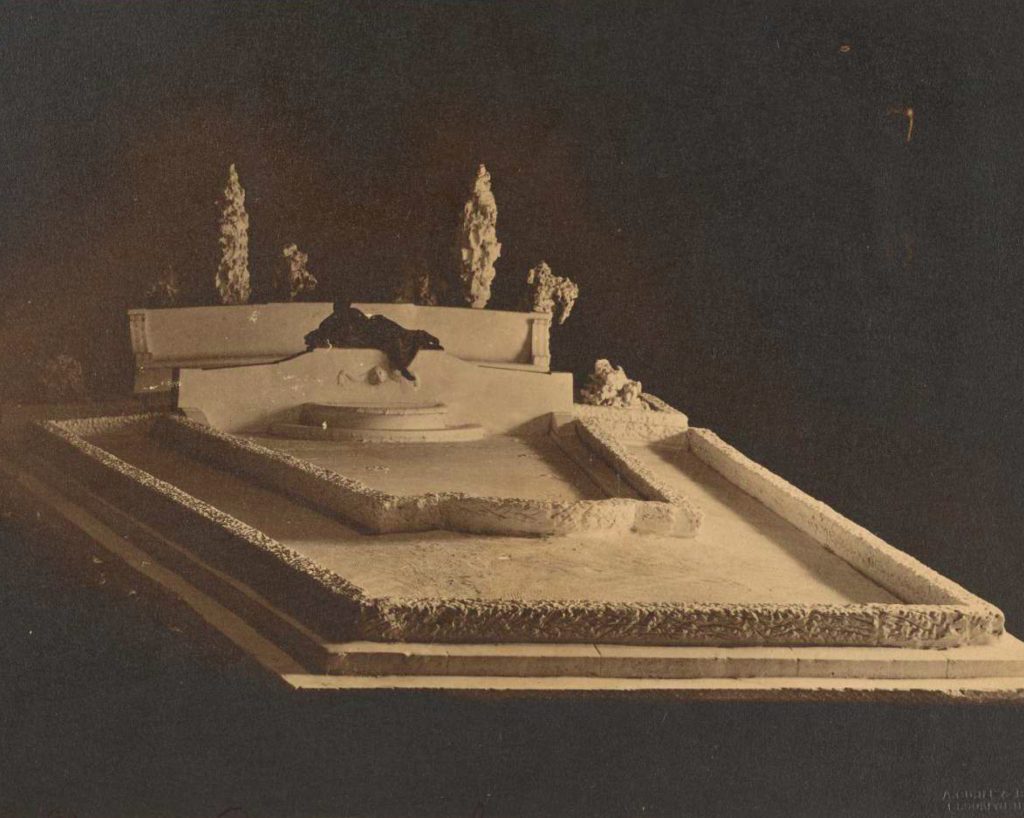

Maquette of “Memory,” Image courtesy Public Design Commission

Henry Hering, Anton Schaaf, Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, Furio Piccirilli —who were they? Mostly unknown today, these four sculptors, were well-known at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th Centuries. All put themselves forward and were the runners-up for the award to create a memorial honoring Isidor and Ida Straus. The couple perished when the Titanic struck an iceberg and went down in 1912.

The sculptor/architect teams who topped the list of contenders won cash awards:

Second Prize, $500—Henry Hering, sculptor, and Charles A. Platt, architect;

Third Prize, $300—Anton Schaaf, sculptor, and Albert R. Ross, architect;

Fourth Prize, $200—Furio Piccirilli, sculptor, and Lord & Hewlett, architects; and

Fifth Prize, $100—Harriet W. Frishmuth, sculptor, and Alexander Deserty, Harold M. Bowdoin, architects.

The models were exhibited in the rooms of the National Sculpture Society, according to The New York Times (Friday, March 21, 1913). Today the NYC Public Design Commission archive holds records for only one model: the winning design, by sculptor Augustus Lukeman and architect Evarts Tracy, that was entered into a competition to determine the choice. The design selection competition was held by the National Sculpture Society in 1912. Dedicated on April 15, 1915, this memorial stands at Straus Park at 106th Street and Broadway.

While no catalog of all the project submissions is to be found, it is possible to glean something about why the committee members chose the Lukeman/Tracy project by looking at it in the context of some of the other entries by the competition’s top four contenders. Collectively these proposals are revealing about how artists at the beginning of the 20th Century expressed emotion. They also raise the question of why that expression makes this work of public art admired and relevant today.

Soon after the Titanic tragedy, a memorial committee was formed and $20,000 in funding for the memorial was raised by public subscription. What was the memorial committee looking for?

As described in The New York Times: “In the rules for the competition the committee had specified that the design should, in a manner, reflect the unostentatious but purposeful character of the citizens to whose memory it was to be erected and that any features that might be termed loud or spectacular should be avoided. It was further required that the fountain should primarily present an object of beauty, without necessarily containing an allegorical expression of any particular theme or subject.”

Model of winning Straus Park design with “Memory,” Image Courtesy Public Design Commission

Achieving agreement on a winning submission was likely to have been complex as often is the case with selection by committee. The group included many NYC notables of the time. Some may have been attached to the style that was typical of the period depicting dramatically posed allegorical figures clothed or partially garbed in flowing Grecian-styled garments.

The winning monument, a bronze of a contemplative woman, was designed to look over a reflecting pool. The original reflecting pool has long been filled with decorative plantings, but the “Memory” statue remains the same.

Much has been written over the past few years about Audrey Munson, the model who posed for this sculpture, and many others in New York City.

Significantly, style had an elevated importance in the NYC of 1913. It was the year of the Armory show that profoundly rocked the art world, introducing international modernist abstract work. Think Nude Descending a Staircase, #2 the painting by Marcel Duchamp exhibited at the Armory show. So, it’s possible that some submissions for the competition by artists, many of whom had received training in Europe, may have been influenced by Beaux Arts classicism or alternatively reached out beyond it.

Artistic quality and justification for who and what was represented in public sculpture was a concern of the time in New York. The Annual Report for the Dept. of Parks in 1914,(p. 41) for example notes:

“Early in the year, a study of the monuments, memorials and other works of art in the public parks and squares revealed an unsatisfactory situation.

Some of these monuments are a just source of pride and delight to our citizens as examples of the prominent places given them.

But it is also very clear that the city authorities in the past have been far too lenient both in appraising the value of the monuments themselves as works of art, and as to the importance of the subjects to be immortalized…”

There was no question that a memorial for the Straus’ was justified. Fundraising for the monument began weeks after the Titanic tragedy. The Straus’ were admirable from many points of view. Isidor Straus was deeply involved in public service and philanthropy. Ida famously gave up a seat in a lifeboat to save the life of a younger passenger.

The Lukeman/Tracy team’s memorial is among the city’s most loved public sculptures. But, it could have gone differently. The three runners-up for the award were all well-known sculptors. Each had a distinctive style. The most distinguishing characteristic of their work seems to be how emotion is portrayed.

Henry Hering made many sculptures that feel fundamentally part of their architectural settings. They often represent allegorical themes or refer to mythology, but are detached from displaying recognizable emotion.

Anton Schaaf was known for busts of military figures. One bas relief, a WWI memorial depicting a woman holding a lantern aloft is austere and unemotional.

Furio Piccirilli was known for busts of notable men and a fewer number of female nudes. He’s not to be confused with his brother Attilio who created the sculptures for the Firemen’s Memorial in Riverside Park, “…one of the most impressive monuments in New York City,” as described on the NYC Parks & Recreation website.

Harriet Whitney Firthmuth is known for works with dancers as models for her figures of sensual, joyful nudes. Among the most famous of her works, “Vine”, is at the Metropolitan Museum. While Firthmuth was admired for the respectful communication she had with her models, the mood of her sculptures seems inconsistent with the solemnity of a memorial.

Portraying emotions of mythic proportions or implying a dramatic back story rather than more lyrical nuances of feeling was typical of many sculptors of the era. An example, unrelated to the Straus memorial, is a sculpture also called “Memory” by the very famous Daniel Chester French, a friend of Lukeman’s, that resides at the Metropolitan.

The subtlety of Lukeman’s lovely figure who appears lost in thought apparently matched the committee’s call. As reported in The New York Times (April 16, 1915) Architect Tracy shared his own feelings at the dedication, “We have sought to make the peaceful spirit of the monument and the tiny pool in front of it the dominating note-an eternal peace that runs through the spirit of the world deeper than its turmoil.”

Observed today, the mood of ongoing wistful mourning seems right. And, while the sculpture is not intended to represent a specific person, the piece captures the impact of loss and power of memory in a way that is both classic and relevant in our time. Significantly, knowing the history of this piece and more detail about this homage to Isidor and Ada Straus’ admirable lives, generosity and self-sacrifice in giving up their seats to other passengers on the Titanic lifeboats.

Asked about the importance of enduring monuments and why they have meaning, Phyllis Cohen, Director of Public Art, Municipal Art Society, said the subject of monuments is currently fraught but that reflection on the sculpture’s place in history, for good or bad, enriches our understanding of our own values. A lyrical essay on this point was made, she says in, The American Monument (1976) by Leslie George Katz with photographs by the renowned photographer, Lee Friedlander.

Whether literally representing a historical figure or an idealized myth connected with that figure, monuments are tied to history. Cohen says that the poet Walt Whitman had strong feelings on the related subject of the importance of the interpretation of monuments by scholars. Whitman wrote about them in A Song for Occupations – 4.

Another take is by Leslie George Katz:

“In the midst of life as much as a curbstone, a public memorial is a gutter of civic memory, collecting runoffs of communal pride. A lot of unsullied meaning lives in these statues. The heart needs landmarks…When the mind forgets, stone and bronze remember…They remind the viewer that the place he inhabits was inhabited before, his life partakes of the poetry of continuum…”