The Orwell, 2 West 86th St.

by Tom Miller

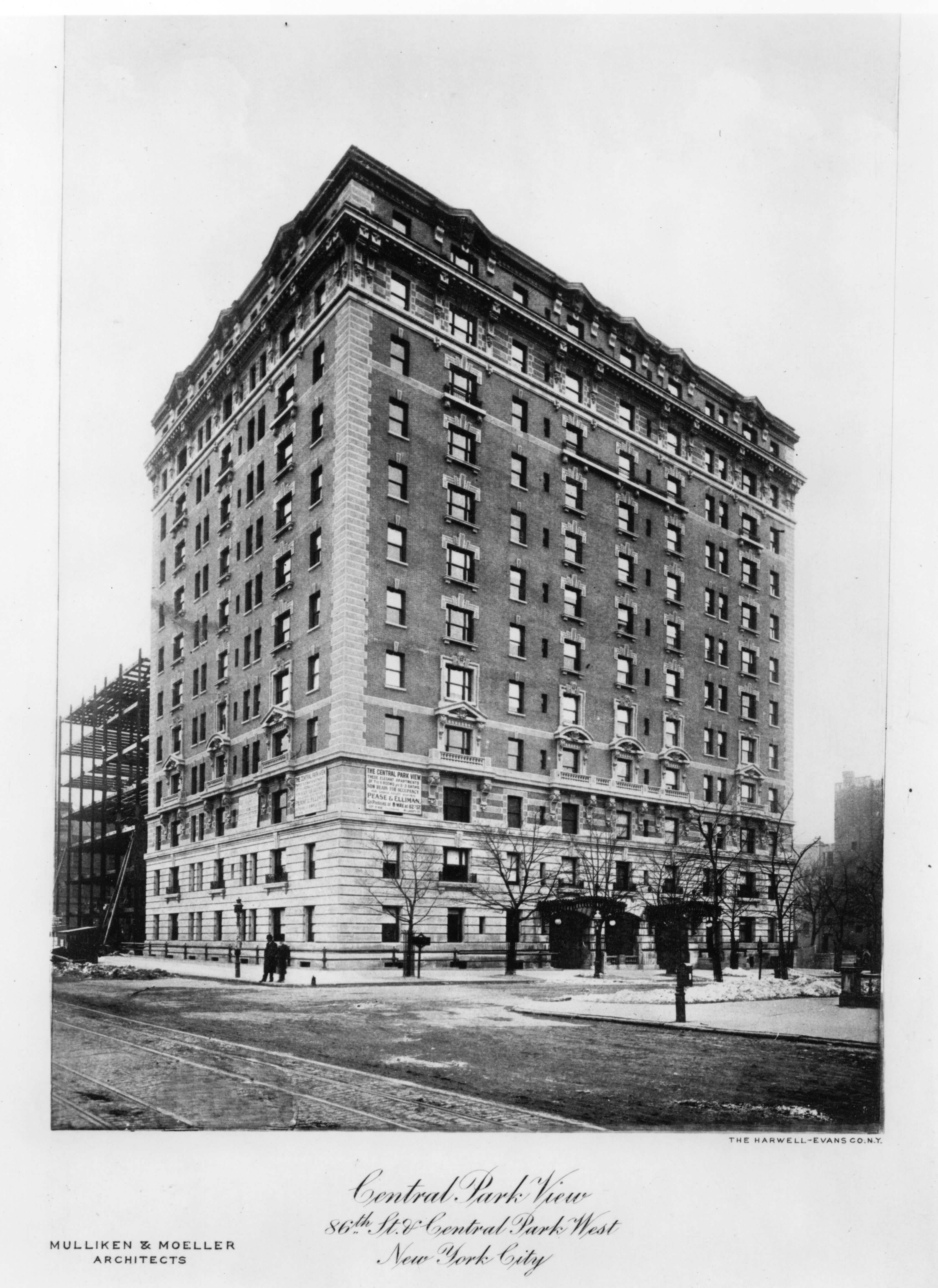

On September 1, 1906, the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide reported that the 12-story apartment building being erected by the Gotham Realty & Construction Co. on Central Park West and 86th Street was nearing completion. The article noted that the $1 million structure (nearly 30 times that much in today’s money) “is arranged in suites for forty-eight families.” Even as the finishing touches were being worked on, Gotham Realty broke ground for an addition on the 85th Street corner. The nearly identical edifices were designed by the architectural firm of Mulliken & Moeller.

The Record & Guide described the architectural style as “French Renaissance…with an exterior of brick with buff limestone trimmings.” But Mulliken & Moeller toned down the style known today as Beaux Arts. Other Beaux Arts style apartment buildings on other Upper West Side, like the Dorilton and the Ansonia, bubbled over with frothy French decorations.

A two-story, rusticated limestone base supported ten floors of deep red brick, highlighted by stone lintels, quoins and scrolled cornice brackets. The 12th floor took the form of a sloped mansard pierced with stone framed dormers.

The entrance to The Central Park View was located on West 86th Street, under a French-style iron-and-glass marquee. The building opened on October 1, 1906, offering residents “elegant housekeeping suites” from 8 to 11 rooms, with two or three baths. A central courtyard provide light and ventilation to the interior rooms.

An advertisement boasted, “Every detail as to finish and for house service carried out to the highest degree.” Importantly, the term “housekeeping” set The Central Park View apart from residence hotels, so popular at the time. It meant that the apartments had kitchens and dining rooms, while amenities like management-provided maid service, for instance, were not included. Living in The Central Park View was not cheap–the 11-room suites rented for $4,000 a year–or about $10,000 a month today. The southern structure, which doubled the size of The Central Park View, was completed in 1907.

But Mulliken & Moeller toned down the style known today as Beaux Arts.

Among the initial residents was Florence Guernsey, an unmarried socialite whose summer home, Cedar Lawn, was north of the city on the Hudson River. Her name appeared in newspapers most often for social reasons. In May 1914, for instance, she hosted the annual meeting of the board of managers of the Free Industrial School and Country Home for Crippled Children; and later that year, in September, she held a “small tea” in honor of her houseguest, Mrs. George Hewlett Clowes.

But in 1908, it was racial inequality that drew her focus. Florence had five servants, four of whom were white and one Black. On April 28 she stopped by the box office of the Colonial Theatre and purchased five tickets for women. That evening Florence was surprised when her Black maid returned, alone, shortly after the group left. When they arrived at the theater, they were told that the Black woman could not sit with her friends, “but must go up stairs where the colored people sat.” She refused to do so, and returned home.

The maid had been with Florence for more than 12 years. Incensed, Florence fired off a letter to the editor of The Dramatic Mirror, which said in part:

“I cannot understand in free America such a condition of affairs, when a thoroughly respectable, well-dressed woman, be she white or colored, should be refused a seat (already bought and paid for) in the part of the house for which her ticket called.”

The Rev. Dr. Charles F. Aked and his wife were also initial residents. Aked was the pastor of the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church–his most prominent congregant, perhaps, being John D. Rockefeller, Sr. A native of Nottingham, England, he had been highly-involved in the Suffrage and Temperance movements there before immigrating to New York in 1907 to accept the church’s pastorship. He was, as well, an ardent pacifist and founded the Passive Resistance League.

Aked and his wife may have chosen The Central Park View on the recommendation of another resident, Carrie Chapman Catt. She was also actively involved in Suffrage and was a mutual friend with the Akeds of Lady Philip Snowden (who preferred the title “Mrs. Snowden”), the famed English suffragette. Carrie Catt and Reverend Aked had more than suffrage in common. She, too, was a pacifist, and in 1915 would help found the Woman’s Peace Party.

Born Carrie Clinton Lane in 1859, she had become involved with the suffrage movement in the 1880’s. In 1900, she was elected president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, taking over for Susan B. Anthony. Her husband, engineer George Catt, died in 1904, leaving her, according to one source, “a wealthy widow.”

On September 23, 1908 the New-York Tribune reported that Mrs. Snowden “arrived yesterday at the home of Dr. and Mrs. Aked, No. 2 West 86th street, where she will be a guest for a month.” The Aked apartment was the scene of a press conference, during which Mrs. Snowden tried to describe the brutal treatment of suffragists in Britain, saying “The things that have been done to the suffragettes by the stewards of political meetings in which they asked questions would not be believed in America.”

Dr. Aked chimed in, saying “It is true that neither Mrs. Snowden’s word nor mine would be sufficient to convince the American public of the things that have been done to those women.”

During her annual visit to America the following year, Mrs. Philip Snowden stayed with Carrie Chapman Catt. The New York Press said on November 4, 1909, “Mrs. Snowden arrived on the Carmania, which docked about eleven o’clock, and went to the home of Mrs. Carrie Chapman Catt…where she received the reporters in the afternoon.” Dr. Aked was present during that press conference. Mrs. Snowden stayed with Carrie Chapman Catt in The Central Park View apartment the following year, as well.

The family of millionaire brewer Anton Schwartz, a partner in the Bernheimer & Schwartz brewery, lived in the building at the time. Schwartz, his wife, and their daughter, Mrs. George Ruppert (the wife of another brewer), were in Europe during the summer of 1910. Their 24-year-old son, Adolf, remained home to tend to business.

The family received an urgent telegram telling them that Adolf was seriously ill. They hurriedly booked passage to New York, but upon their landing on October 11, they were told that Adolf had died the previous day.

They hurriedly booked passage to New York, but upon their landing on October 11, they were told that Adolf had died the previous day.

Anton was grief stricken. According Mrs. Max Bernheimer, the wife of his partner, “the father was wrapped up in this son, whom he expected to succeed him in the business.” He shut himself inside the apartment, The New York Times saying on November 7, “For two weeks the elder Schwartz had not been at his office.” Finally, his emotional anguish took its toll. The newspaper reported that Schwartz “committed suicide by shooting himself yesterday morning in his apartment on the third floor of the Central Park View Apartment House.”

Broadway producer Henry B. Harris and his wife, Renee, lived here by 1912. In April that year, they were returning home from Europe on the R. M. S. Titanic. On the afternoon of April 14, the couple joined a card game in the lavish stateroom of Lady Cardeza and her 40-year-old son, Thomas. (That same promenade stateroom was used by filmmaker James Cameron as that of despicable character Cal Hockley in his 1997 film, Titanic.)

Carefree cardplaying turned to terror that night when the ship struck an iceberg. Later the New-York Tribune recalled, “Henry B. Harris, when the Titanic was sinking, had been helped into one of the small boats with his wife, when an officer called out, ‘Women and children first!'” Harris looked at his wife and said, “That’s right,” and stepped back onto the ship. Renee’s boat was lowered to the ocean and rowed away.

When the monument to Isidor and Ida Strauss, Memory, was unveiled in April 1915, survivors were invited to participate. Renee Harris could not bring herself to do so. On April 16, the New-York Tribune noted, “In her home, at 2 West Eighty-sixth Street, Mrs. Harris sat alone with the little dog which has been her companion for ten years.” She explained to the reporter, “I can’t talk about the Titanic. It is all too dreadful to think of, and I have trained myself to keep it out of my mind.”

The Central Park View had been the scene of another tragedy two years earlier. Joseph Skolny was the head of the clothing manufacturing firm Joseph Skolny Co. He and his wife had two live-in servants, Josephine Romer, the cook, and 22-year-old Anna Schaefer, a maid and companion to the Skolny’s daughter, Rosa.

In the fall of 1913 Anna showed signs of what today might be diagnosed as a brain tumor. She began having excruciating headaches and her eyesight was failing. Rosa took her to a specialist, who said she simply needed eyeglasses. The Sun reported that the severe headaches made Anna “fear that glasses could not remedy the defect.” She and Josephine shared a bedroom, and as they prepared to go to bed on December 22, Anna said, “If it weren’t for you, I’d kill myself.”

The following morning the women arose and went into the kitchen to start the day. Josephine walked out for a moment, and when she returned, Anna was gone. The Sun reported, “A chair placed in front of an open window told the story. The superintendent of the house found her body on the ground.”

It was around this time that the Japanese Government leased an apartment for its Consul General, Kametaro Iijima, who arrived in New York in June 1913. The Iijima’s four-year-old daughter, Mosa, was playing in front of the building on March 22, 1914, directly across from the mansion of James “Diamond Jim” Buchanan Brady, at 7 West 86th Street. Brady’s chauffeur, Ray Lascher, was bringing the automobile around when he struck the little girl.

The New York Press reported that Lascher carried Mosa to her apartment. Dr. Joseph Weinstein was called, who happily said she “was suffering from shock, but was not otherwise injured.”

Iijama’s successor, Consul General Chenosuke Yada and his wife, took over the apartment around 1917. On November 26 that year, Mrs. Yada entertained the Women’s Oriental Club. The New York Times reported, “Jean Bol, a Belgian tenor and recent war refugee, sang.”

Early in 1919 the Peter Stuyvesant Operating Corporation leased the building and hired the architectural firm of Schwartz & Gross to convert it to a residential hotel. On March 16, The Sun reported that it “is to be converted into the highest type of apartment hotel, containing on the upper eleven floors about 350 rooms and 200 baths. The first floor will be used for a restaurant, lobby and reception hall.”

The two-year conversion was completed in 1920. Now known as the Hotel Peter Stuyvesant, there were 19 apartments per floor. An advertisement in The Sun on June 27, 1920 touted “Special Summer Rates” and offered “Suites of one room to as many as required, furnished or unfurnished.”

The conversion did not mean that all of the former residents evacuated. The Yada family, for instance, was still here in 1920. The long-term residents, for the most part, continued to be affluent. Such was the case with the widowed Mrs. Elizabeth Bruch, who lived here with her 24-year-old son, Russell, in 1921.

That year the Bruches spent the summer season at Sound Beach, Connecticut, staying at the Greenwich Inn. On the evening of August 7 at around 7:00, Russell took a canoe onto the Long Island Sound. He never returned. Two days later the New York Herald reported, “His mother, Mrs. Elizabeth Bruch of the Hotel Peter Stuyvesant, is prostrated at [the] Greenwich Inn.” Police had notified distant communities “on the theory that the young man may have been carried far into Long Island Sound,” said the article.

Five days after Russell’s disappearance, his mother offered a $50 reward ($725 in today’s money) “for information leading to the recovery of the canoe,” according to the New-York Tribune. “She believes that finding the craft might help to locate her son.” But, tragically, the next day searchers in a small boat discovered his body. The New-York Tribune said on August 13, “To-day the body came to the surface. The canoe has not been found.”

A socially-visible resident in the mid-1920’s was Jesse Winburn, head of the Jesse Winburn Banking and Investment Company and of the New York City Car Advertising Company. An avid sportsman, in 1923 he loaned 1 million francs to the French Olympic fund to stage the Olympic games in Paris.

On December 20, 1926, The New York Times reported that Winburn had given a musical the previous afternoon. Among the guest list were socially elite surnames like Rappaport, De Witt Rogers, and Crouch. Following Winburn’s death at the age of 58 at his summer home in Rye, New York, his estate was estimated at about $1.6 million–or around $24 million today.

In 1939, with Prohibition having ended five years earlier, a cabaret and piano bar was installed in the ground floor. Two years later the building was sold to the Wilger Realty Corporation. The Hotel Peter Stuyvesant was sold again in July 1960.

Among the residents at the time were renowned explorers Irvin Baird and Jill Cossley-Batt. Irvin had also been a correspondent for Reuters in India. The two had led an expedition into the Himalayas in 1931-32 where they discovered an isolated tribe that, according to their reports, lived to “great age and free of disease and pressures of civilization.” The people were believed to be one of “the lost tribes of ancient Chaldeans.” Following that expedition they were married by a missionary in Darjeeling, India. Irvin Baird died on January 30, 1964 at the age of 63.

The building was purchased in 1968 by Simon Haberman, who initiated a substantial renovation, completed in 1970. The project reworked the floorplans and converted most of the first floor to a medical center. A new main entrance was created with the address of 257 Central Park West. Now a cooperative apartment building, Haberman renamed it The Orwell House. An advertisement in The Sunday News on May 10, 1970 described, “Luxury Coop Bldg / Complete reconstruction has resulted in one of the finest & most complete deluxe Coop apt bldgs in all of Manhattan.”

A decade later Haberman explained the name to The New York Times writer Edward Deitch, “I like [Orwell’s] books. I read ‘Animal Farm’ in high school and found it delightful.'” Haberman, himself, lived in the The Orwell House, and told Deitch that his homage to the author went so far as to sometimes use the name George Orwell, Jr., although “just kiddingly.” Deitch noted, however, “Kidding or not, there is a George Orwell, Jr. listed in the telephone book. The address is 257 Central Park West–Orwell House.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

RETURN TO CENTRAL PARK WEST

BUILDING DATABASE