By Megan Fitzpatrick

In 1825 African Americans began to migrate upwards to the West 80s between Seventh and Eighth Avenues to settle down at a time when the Upper West Side was mostly rural and Central Park had yet to be carved out. Over the next 30 years the community known as Seneca Village grew. According to the 1855 census it became home to around 264 residents – two-thirds African American, one-third Irish immigrants, and a handful of German immigrants. It comprised approximately five acres of land – contained within it 52 houses, three churches and cemeteries, two schools, numerous gardens, and several barns and stables.

Through the process of eminent domain, residents were forced to leave and all structures standing there were condemned to prepare for the creation of Central Park. As plans to build the park developed, the community was negatively characterized by newspapers and park advocates. To facilitate evictions, the village was portrayed as a “shantytown” or “wasteland” occupied by “squatters,” and a myriad of other demeaning terms. Many residents fought for the right to keep their land and their community intact through the legal system, filing objections to their forced removal. The residents of Seneca Village were given final notice to leave in the summer of 1856. Some are known to have left New York; others settled in other parts of the city or on Long Island. By 1857, a groundbreaking community, founded on the cusp of the emancipation of enslaved peoples in New York City—had vanished without leaving much evidence of its past. To date, no living descendants of a Seneca Village resident have been located.

Houses

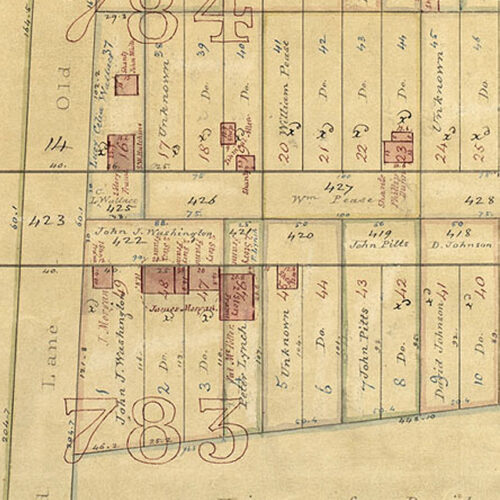

By 1855, about half of the African American population in Seneca Village owned their homes, making it the largest community of African American property owners at the time. It began when Andrew Williams, a young African American, purchased three lots from the owners John and Elizabeth Whitehead on September 27, 1825. Significantly, property owners were the only citizens allowed to vote at the time, a basic right held mostly by white residents. However, in 1821, New York State ruled that in order for African American property owners to vote their property must be worth at least $250. With that rule in place, 10 African Americans in Seneca Village had the right to vote in New York City.

What we know about these houses in large part came from excavations undertaken in 2011 which uncovered aspects of the everyday life of the people of Seneca Village. Apart from maps, there is little documentation on this site so excavations were able to tell a deeper story, for example, the excavation of the Wilson House highlighted the life of William G. Wilson, his wife, and, eight children. Aspects of identity and daily life were extracted from the materials like dishware found in the lost village that was only occupied for about three decades.

Religious Buildings

Although detailed information about other structures in the village is scarce, it’s clear religion played a significant role in this small community as records show there were three churches on the site.

African Union Church

The first church in Seneca Village was a branch of the Methodist Church African Union, built around 1840 near west 85th street. The congregation, originally from Wilmington, Delaware, set up this satellite church to serve the growing African-American population. The churchyard contained within it a small burial ground. Census records, which often gave insight into the occupations of the residents, highlighted that a man named William Mathews, originally from Delaware, worked as a sexton, maintaining the church and churchyard.

African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion Church

The members of AME Zion Church were one of the first property owners in the village when the churches’ trustees purchased six lots near 86th Street on September 27, 1825, for use as a cemetery for African Americans. AME Zion, with its home on Leonard Street, was the earliest African American church founded in New York City and maintained its position as one of the largest and most prosperous congregations for African Americans in the city. Although they were the last to construct a church in Seneca Village, their long presence in the community is significant and represents the strong connections between African Americans downtown and in Seneca Village. They also maintained a school in their basement.

All Angels Church

All Angels’ was a missionary parish founded in 1846 as an affiliate of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church located at Amsterdam Avenue and 99th Street. The Seneca Village branch began as a Sunday School in 1833 and a church was later established in 1849. Contrary to the African Union and AME Zion Churches, this church was racially integrated of both African Americans and European immigrants living in the village. After the original wooden structure was demolished in the construction of Central Park, the church moved nearby to West 81st Street and West End Avenue.

Schools

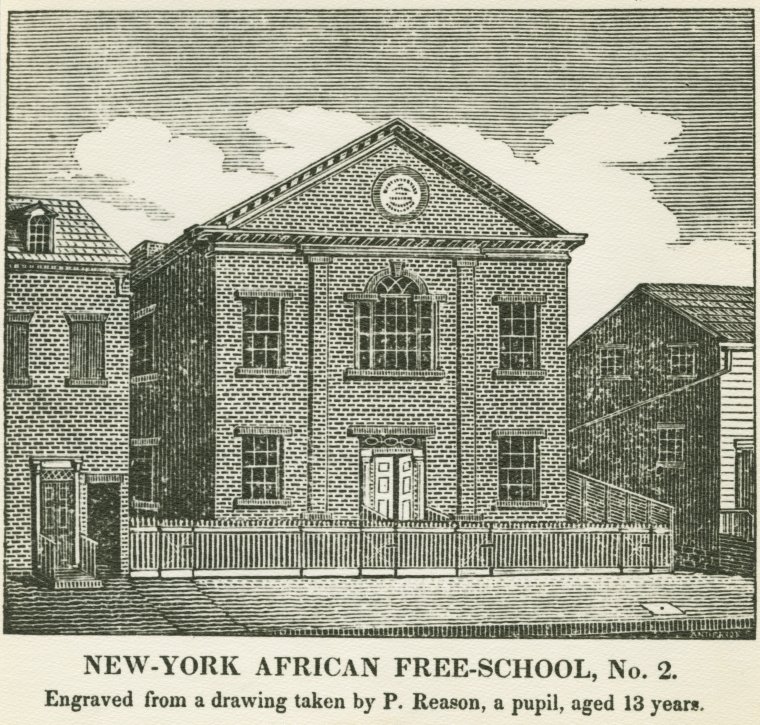

There were two schools that served the children of the community, one in the basement of AME Zion Church and the other was a city school, Colored School No. 3. Located next to the African Union Church, city schools such as Colored School No. 3 evolved from institutions founded by the New York Manumission Society, for example, the African Free School No. 2 located on Mulberry Street. This abolitionist organization led by influential white New Yorkers provided education to the children of enslaved people and free African Americans. Catherine A. Thompson was recorded as the school’s teacher at age 17, and because of her efforts, the school was successful with a comparatively high percentage of African American families in Seneca Village sending their children to school.

Throughout Black History Month, we’re exploring significant places of Black History in our neighborhood.

References:

Images:

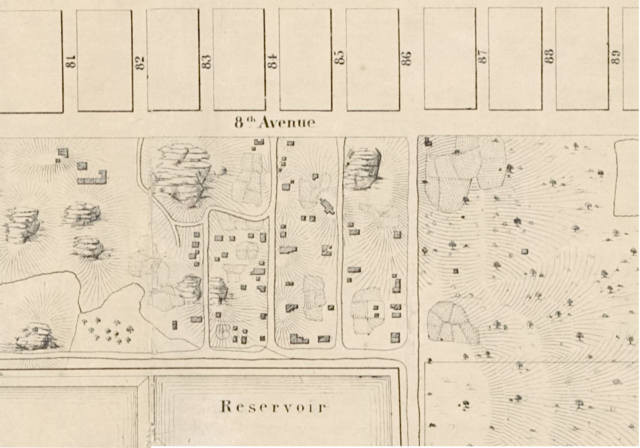

1. Map showing Seneca Village, Egbert Viele, 1856, Courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives.

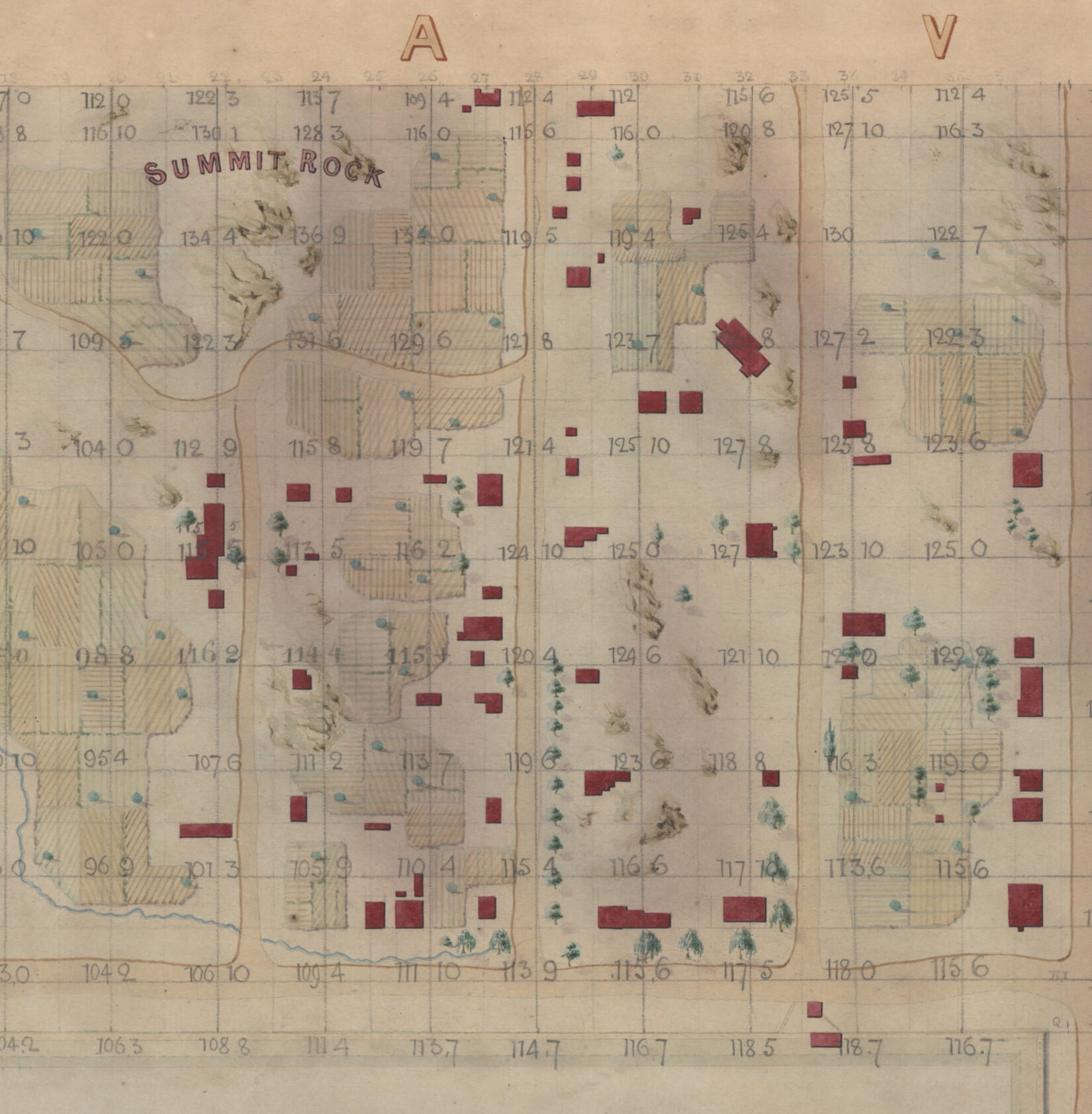

2. A closer look at the detailed map showing land formally known as Seneca Village, Egbert Viele, 1856, Courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives.

3. Seneca Village houses documented in the Sage Condemation Maps, 1856. Courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives.

4. The original wooden church of All Angel’s Church in Seneca Village. Courtesy of All Angels Church.

5. The school in Seneca Village would have resembled the African Free School No. 2 located on Mulberry Street, 1860. Courtesy of the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture, NYPL Digital Collections.

All Angels Church, ‘Our History’, 2023.

Central Park Conservancy, ‘Discover Seneca Village’, 2020.

Central Park Conservancy, ‘Dishes, Shoes, and Tiles: The Excavation of the Seneca Village Site’, 2019.

John Titor, ‘The Story of the African-American Community that Died so Central Park Could Live’, History Daily, 2017.