The Jewish Center

131 West 86th Street

by Tom Miller

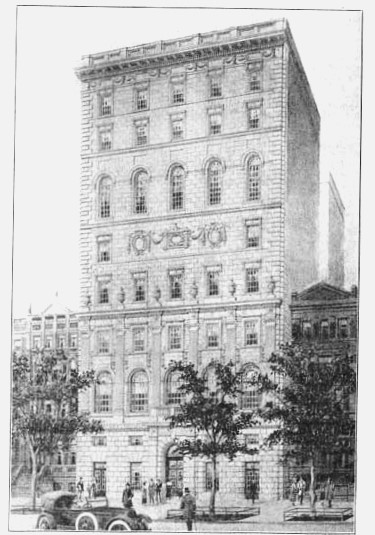

On April 1, 1916, the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide reported on “a unique building operation which will be erected at 131-135 West 86th street. The project will be known as the Jewish Center and will combine the features of a synagogue, settlement home, and social center.” The 29-year-old architect Louis Allen Abramson had been hired to design the six-story structure, which The Reform Advocate said, “will contain a synagogue, a library, gymnasium, kindergarten, public hall, roof garden, and class rooms for educational work. The centre will be for young people particularly.” The article explained, “the building will be for the use not only of people of the west side, but also for organizations connected with west side synagogues which are not without adequate meeting rooms.”

And then the trustees of the newly formed organization expanded their vision. On January 26, 1917, The Sun reported that the building would rise eight stories. “Former plans were for a six story building,” said the article. No doubt, because funds were still being raised, the project went forward in two parts. Abramson filed plans for a four-story structure in May 1917.

The cornerstone was laid on August 4, 1917, “in the presence of 100 members and guests of the organization,” according to The New York Times. Among the speeches was one by Professor Mordecai M. Kaplan, who would be rabbi of the congregation. He “said that the purpose of the organization was to encourage Jewish culture, thought, customs and social life,” related the article.

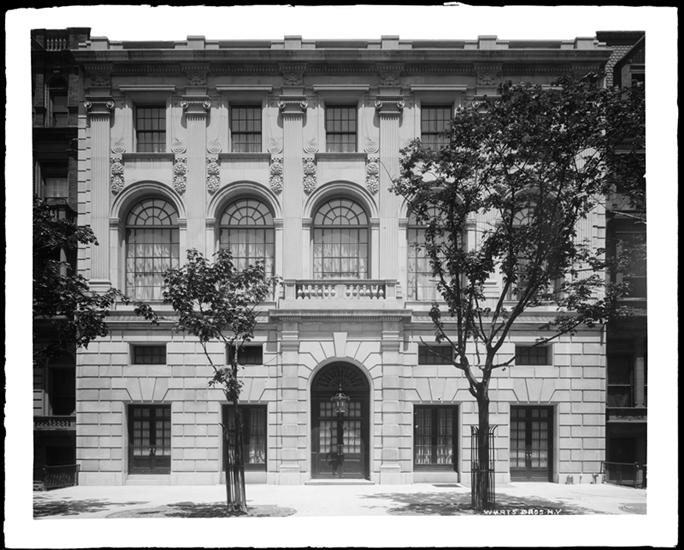

The first stage was completed in the following year. In February 1918, a month before the dedication, the Real Estate Record noted, “The new structure is now erected so as to include the cornice directly over the fourth story. Provisions have been made so that in [the] future the superstructure may be added.”

The article said “The facade of this structure has been designed in a severe early Italian Renaissance style and has been constructed of Indiana limestone and granite.” On the first floor were the lobby and Adam style auditorium (or “public hall”). The synagogue engulfed the third and part of the fourth floors. The other half of the fourth floor held the library, trustee’s room, and a gallery. Without further explanation, the Record & Guide said, “The synagogue is interesting in that it has a seating arrangement that is novel in the manner in which the sections for men and women are segregated.”

On July 26, 1919, the Record & Guide reported that construction was about to start on the additional floors.

The building formally opened on March 22, 1918, “with considerable formality,” as described by The Sun. Two days later, it was dedicated. The celebrations began at 10:30 on the morning of the 24th with “a children’s festival, ‘The Land of Aleph Bes,’ a Jewish fairy play.'” It had been written for the occasion by Samuel S. Grossman. The article noted, “At 3:30 in the afternoon a number of distinguished rabbis and citizens will formally dedicate the structure.”

The auditorium was the scene of the Zionist summer lecture course that year, run by the Intercollegiate Zionist Association. The New York Herald reported on July 8, “These lectures will be delivered from two to five o’clock each afternoon on the problems arising out of the re-establishment of a Jewish State in Palestine and other aspects of Judaism.”

As summer drew to an end, the organization announced that Jews without a permanent synagogue were welcome to attend holiday services here. An announcement in The American Jewish Chronicle on August 30, 1918 said in part:

The Jewish Center of 131 West 86th Street, a self-supporting social and religious center for the Jews of the neighborhood, has at its disposal a number of seats for non-members, who wish to worship in its synagogue on the coming High Holidays.

Those who will avail themselves of this offer will be made to feel perfectly at home, and will have an opportunity to become acquainted with the character and purposes of the Jewish Center which has recently been established.

On July 26, 1919, the Record & Guide reported that construction was about to start on the additional floors. The total cost of both projects came to just over 7 million in 2023 dollars. The journal said the addition would hold “gymnasium and exercise rooms, a natatorium and baths (“including steam and hot rooms, showers, etc.”), and class and club rooms.

The Jewish Center became an important meeting venue and cultural space. On October 24, 1920, for instance, The Brooklyn Standard Union reported on the annual meeting of the Jewish Welfare Board. In addition to a memorial address on the passing of the former chairman, the article said, “It is also expected a moving picture of the welfare work of the board during the war will be presented.”

And three months later, in January 1921, an exhibition of Jewish-Polish artists was held in the gallery. Among the Committee of Hostesses for the event were women with some of the most recognizable surnames in the Jewish community, including Straus, Wertheim, Guggenheimer, and Lewisohn.

Storm clouds had been forming over the Jewish Center at the time of that exhibition. Rabbi Kaplan’s reformist views on Judaism had shocked several of the trustees. In their 1997 book A Modern Heretic and a Traditional Community — Mordecai M. Kaplan, Orthodoxy, and American Judaism, Jeffrey S. Gurock and Jacob J. Schacter quote a letter Kaplan later wrote to Carl Hermann Voss. He said in part, “the board of directors objected to my having published in the Menorah Journal of 1920 the fact that Judaism is in need of reconstruction.”

In fact, the dissatisfaction went beyond that incident. The New-York Tribune explained on December 29, 1921, that the disagreement within the trustees and the congregation had “developed over the non-orthodox views and teachings of Dr. Modecai Kaplan.” The problem stemmed from Kaplan’s expressing doubt on the authenticity of parts of the Torah, or Old Testament. A proponent of “progressive Judaism,” he had proposed that the story of the tablets handed down to Moses at Mount Sinai and similar biblical narratives were “of a seemingly mythological nature.” The article added, “he is said to have advocated practical modifications of the dietary laws and other forms of procedure contained in the Jewish religious code.”

So severe were the tensions that Kaplan had voluntarily taken a leave of absence beginning in August that year. “His term as rabbi expires next April,” said the article. When the center’s treasurer, Arthur M. Lamport, was asked about the problem by a reporter from the New-York Tribune, he was purposely vague. He urged that there “are no serious differences extant in the Jewish Center.” But he added that the reporter would not understand them, anyway, saying, “those that do exist are theological and therefore too profound for off-hand discussion.” Kaplan was replaced by Dr. Leo Jung, whose religious views were more in line with the trustees and congregation at large.

The center continued to be the venue for a variety of activities, meetings and lectures. The Collegiate Committee of the Women’s Branch of the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America held a Chanukah party on December 2, 1923, for instance; and on November 20, 1925 Tax Commissioner Henry Payne spoke in the auditorium “The Influence of Theodore Roosevelt.” The following month The Menorah Journal hosted a dinner here.

The focus within the Jewish Center would soon turn to Europe, as the Nazi Party gained power. On April 29, 1933, Rabbi Leo Jung took advantage of President’s Day to compare President Franklin D. Roosevelt to Chancellor Adolph Hitler. He said in part, “against the barbarous bigotry of Adolph Hitler” the President “stands, the ideal leader of his people, pointing by his own example the way toward the humanization of humanity.”

…affectionately known by members as “the first Shul with a pool.”

Jung had just received a bizarre communication from Berlin dated March 25, 1933, from Rabbi Dr. Esra Munk. It was either a forgery, sent by Nazi propagandists, or it was forced. Quoted in Marc B. Shapiro’s Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy, it said in part:

Reports, flagrantly in conflict with the facts, of atrocities against the Jews in Germany have caused me, with the full agreement of all my colleagues, to direct this appeal to you as a friend of long standing…imploring you to denounce, categorically and with the utmost emphasis, such reports as criminal, because they are contrary to the truth and monstrous exaggerations of the excesses of individuals during the elections.

Dr. Jung seems to have been unswayed by the suspicious letter and continued his vocal campaign against Nazism and anti-Semitism.

Not all of the Jewish deaths during the war were the result of the monstrous actions within the Nazi concentration camps. American soldiers fell in battle, and the first from New Jersey to die in action at Pearl Harbor was Private First Class Louis Schleifer, an air mechanic. On June 30, 1942, a memorial service for the young soldier was broadcast over radio from the auditorium of the Jewish Center.

In the third quarter of the 20th century, outside groups were renting space in the building. June Day Camp, Inc. operated here in the early 1970s, and in the 1980s the Performing Arts Repertory Theatre Foundation, Inc. had its headquarters here. At the same time, the Aerobics West Fitness Club operated in the Jewish Center. In June 1986, it titled an advertisement, “Who says the meek shall inherit the earth,” and promised, “At Aerobics West Fitness Club, we turn the meek into the sleek.” The advertisement ended with, “As fate would have it, we’re located in a temple.”

The 21st century saw the Manhattan Jewish Experience on the fourth floor. Catering to adult students, it offered “a full schedule of basic courses for free, including the Monday Night Lounge, which includes a sushi dinner and interesting discussions of how current issues (sexuality, free will, business and medical ethics) relate to the ancient religious, followed by music and dessert,” according to The Cheap Bastard’s Guide to New York City in 2008.

Also operating from the building was PresenTense Group, which promoted itself in 2013 as “a largely volunteer-run community of innovators and entrepreneurs, thinkers and leaders, creators, and educators, from around the world, who are investing their ideas and energy to revitalize the established Jewish community.”

The Smith School, which caters to “students with a variety of learning and social-emotional needs,” was in the building by 2010, and the Drisha Institute for Jewish Education occupied part of the 9th floor by 2019.

Importantly, the building continues to house a modern Orthodox synagogue (affectionately known by members as “the first Shul with a pool”). Few casual passersby would suppose the handsome neo-Classical style structure is a synagogue. And almost no one could guess that Louis Allen Abramson purposely (and adroitly) designed it in two parts.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Be a part of history!

Stay local to support the nonprofit currently at 131 West 86th Street: