The Clarendon – 137 Riverside Drive

by Tom Miller

Anita and Millicent Willson were the daughters of vaudeville entertainer George Willson. They followed in his footsteps, and in 1897 were performing as “bicycle girls” in Edward Rice’s production of The Girl from Paris at the Herald Square Theatre. The beautiful 16-year old Millicent caught the eye of William Randolph Hearst, who was more than twice her age.

The intentions of wealthy older men towards pretty showgirls were always suspect; so Anita Willson, who was a few years older than Millicent, tagged along as chaperone on the initial dates. On April 28, 1903, six years after meeting, the couple was married.

Hearst, whose passion for politics equaled or surpassed his fervor for publishing, had taken his post as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives a month earlier. At the end of his term, in March 1907, he looked for a new home for his family, which now included three-year old George.

At the time, the Upper West Side was seeing private mansions, most built not more than 15 years earlier, being razed and replaced by modern apartment buildings. At the southeast corner of Riverside Drive and West 86th Street developer Ranald H. MacDonald was completing his 11-story Clarendon, designed by Charles E. Birge.

The Clarendon offered nothing in terms of outward ostentation. Completed in 1908, its neo-Renaissance facade of limestone and red brick had, instead, the personality of a wealthy dowager–aloof and proper. Intended for upper-class residents, there would be just two apartments per floor. The living rooms were 22 by 30 feet, and the dining rooms 19 by 23 feet. The Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide pointed out “The rooms in all cases are grouped around the foyer hall, and in no case is it necessary to pass through a bedroom to enter a room, a very important point.”

An advertisement described the apartments as “consisting of ten to twelve rooms and four bath rooms to each apartment” and noted, “The servants’ quarters are cut off with a separate entrance from the public hall, thus giving the same privacy one would have in a private house. Separate servants’ elevator lands tradesmen, etc. direct to the kitchen door.”

The exception was the uppermost apartment. Hearst negotiated with MacDonald to configure the top three floors into a single, lavish residence. The family moved into their 30-room apartment in April 1908, paying $24,000 per year in rent–just under $640,000 today.

The Clarendon offered nothing in terms of outward ostentation.

Ranald MacDonald, too, moved into his new building. His apartment was the scene of his mother’s funeral on November 18, 1910.

The Clarendon by then was filled with millionaires. Their wealth was reflected in their expensive limousines and touring cars. In 1914, Charles W. Baker owned a Pierce Arrow and a Cadillac; William J. Sloane, Francis L. Leland, Richard E. Breed and Amos L. Beaty all owned Packards; while Julius Siegbert had a Cadillac.

But it was, of course, the Hearsts who drew attention.

Hearst had launched unsuccessful bids for President (in 1904), for Mayor twice, and for Governor in 1906. His disappointing campaigns did not dampen his enthusiasm for politics; a fact reflected in many of the entertainments the Clarendon apartment.

On February 20, 1911, they hosted a dinner for Congressman Champ Clark and his wife. Among the many guests were three senators and three congressmen and their wives. A special train had been hired to bring these guests from Washington. The New York Times commented “After dinner there was music by Franko’s Orchestra and Miss Ada Sassoli, harpist. Elsie Janis and Joseph Cawthorn gave monologues and impersonations.”

When the Hearsts gave a dinner in honor of William’s mother, Phoebe, a few weeks later, more senators and representatives were brought in from Washington. The guests were entertained by a host of performers after dinner that evening, including the famous comic duo Weber and Fields.

A rare incidence of another resident’s stealing the headlines came on February 20, 1912 when Francis L. Leland, the president of the New York County National Bank, gave the Metropolitan Museum of Art a gift of bank stock valued at more than $1 million.

Museum vice-president Robert A. de Forest told reporters “While the gift is absolutely unconditional, the trustees of the museum, in my judgment, will hold it as a principal fund, the income of which will be used chiefly, not entirely, for the purchase of art.” The donation became the Leland Fund, the annual income from which, at the time, was estimated at $48,000.

By 1913, Hearst’s nearly manic collecting of art and antiques required more space. Most problematic, though, was an oversized medieval tapestry he had brought back from Europe. He needed to raise the ceiling height to accommodate it.

Hearst approached Ranald MacDonald with a request to enlarge his apartment. Most likely, considering the future likelihood of leasing the gargantuan space, MacDonald refused. And so in true Hearst fashion he purchased the entire building. The price was reportedly around $1 million.

He brought back Charles E. Birge to increase his apartment to include the 8th through 11th floors, as well as adding a somewhat awkward-looking mansard on the roof which included a giant skylight to illuminate the two-story space below. He could now hang his tapestry.

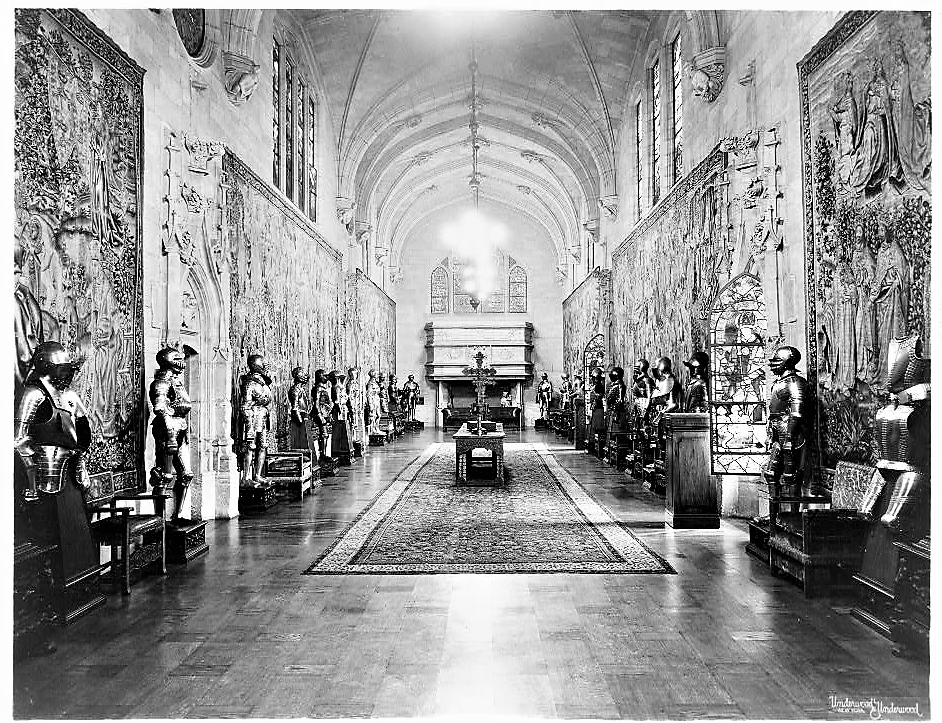

Hearst installed built-in cabinets to display his collection of silver salvers, and brought in 15th century stained glass and carved woodwork. According to Andrew Alpert in his Historic Manhattan Apartment Houses, “There was a Georgian dining room, a French Empire bedroom and bits and pieces of almost every other architectural and decorating style that ever existed. Perhaps the most archetypal ‘Hearstian’ room, however was the triple-height vaulted stone hall.” That room housed the mogul’s substantial collection of medieval armor.

Construction did not slow down the Hearsts’ entertaining. For their 10th wedding anniversary–their tin anniversary–they hosted a dinner and dance on April 28, 1913 attended by notable names in politics, the military, and society. The New York Times reported “The menus were engraved on a thin scroll of tin, with a photograph of Mr. and Mrs. Hearst at the top of the scroll. The entire service for the supper was in tin.”

A month later, following the dedication of the Maine Monument in Central Park, they gave a reception, dinner and dance for the officers of the United States Atlantic Fleet. Mingled among the impressive display of dress uniforms were the Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels; Secretary of War, Lindley M. Garrison; senators, admirals, and the Governor of New York.

On December 3, 1915 The New York Times reported on the arrival of twin boys in the Hearst household. The couple now had five sons. The newspaper whimsically said “The oldest, George, is 11 years old; William is 7; John 5, and the last two, for whom no names have yet been chosen, are not old at all.”

The family’s live-in staff at the time included a parlor maid, kitchen maid, cook, waitress, maid and steward.

Two frequent visitors around this time would later cause the Hearsts much unwanted publicity. Count Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff, the German Ambassador visited often until about December 1916. Bernstorff’s close friend, Bolo Pasha was another repeated guest.

And in true Hearst fashion he purchased the entire building.

The problem for the Hearsts was that they were later exposed as German spies. Hearings in the United States Senate in 1918 resulted in full pages of testimony being printed in newspapers nationwide, telling of the agents coming and going from the Clarendon apartments.

One of the witnesses, the Clarendon’s superintendent Charles H. Jerome, told of the drastic steps Hearst took to avoid reporters and investigators. On August 12, 1918 he testified “While I was at 137 Riverside Drive Mr. Hearst had an iron bridge built from the roof of 137 Riverside Drive to the roof of an adjoining apartment call The Netherlands, and that Mr. Hearst often used that bridge as a means of leaving 137 Riverside Drive without passing down by way of the elevator and out of the front door.

“During this time persons looking for Mr. Hearst, including process servers and the like, used frequently to stand in front of the building waiting for him to come out, and by this means he avoided being overtaken by them and served with papers.”

Life in the Clarendon was less tranquil beginning in 1919. Hearst had been carrying on an affair with film actress and comedian Marion Davies and that year he started construction on his massive California mansion, Hearst Castle. Upon its completion, he spent little time in New York, openly living with his mistress.

Millicent, at least initially, kept up appearances. On December 30, 1922, with 19-year old George home for the holidays from college, she gave a party for his friends. The New York Herald reported, “Young men and women, home for the holidays from schools and colleges, had a merry reunion last night as guests of Mrs. William Randolph Hearst.” The article noted, “Typical holiday merriment started with a dinner. Then there was an hour of vaudeville and the showing of some new motion pictures. A dance followed, divided into two parts by supper.” There was no mention of George’s father.

Nevertheless, Hearst did make appearances and Millicent maintained her role. On December 20, 1927, the couple hosted a dinner prior to the Cholly Knickerbocker Charity Ball. The guest list included three princes, Mrs. William H. Vanderbilt, Mr. and Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs and Mrs. Anthony J. Drexel Biddle, Jr. among other high-society names.

The following year Millicent’s dinner guests included Prince Ludovico Spade Potenziani, the Fascist Governor or Rome and his daughter Princess Miriam; and later Grand Duke Alexander of Russia and the Grand Duchess Marie.

By now, she was separated from her husband; although they never divorced. On October 18, 1929, her guest of honor was Winston Churchill. The New York Times said, “The dinner was served at a long flower-banked table in the Tapestry Room, and later there was dancing in the gallery. During the evening a specially arranged motion picture news reel was shown, it’s various flashes depicting some of the guests at important events in the past.” Among those guests were the Vincent Astor, the William K. Vanderbilt, the Jay Gould, Lord Feversham and Prince Serge Obolskeky. The article mentioned that Rudy Valle’s orchestra played for the dancing.

In the early 1930, Eleanor Roosevelt was the guest of honor in Millicent’s dining room several times. But by now, unknown to most, William Randolph Hearst’s financial empire was crumbling. While rival newspapers thrived, circulation of his major publications plummeted. Instead of cutting back on expenses, he continued to spend lavishly on art and refused to sell his magazines or newspapers.

He began selling off real estate after his financial advisors informed him he was tens of millions of dollars in debt. By 1938, it was not only his real estate, but also his beloved collections that were on the market. A series of auctions sold off paintings, furniture, silver, tapestries and other valuable belongings. At one sale, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. purchased $100,000 of antique silver for his Colonial Williamsburg project.

The gargantuan Clarendon apartment could not last. On August 27, 1939, The New York Times reported that “Plans were filed a few days ago for renovations to the old twelve-story apartment house at 137 Riverside Drive. By architect C. B. Ferris.” The building had been lost in foreclosure to the Mutual Life Insurance Company, and agents said the plans “were in an indefinite state and the exact nature of the proposed work was still undecided.”

Eight months later, they were decided. On April 7, 1940, Mutual Life Insurance Company announced that the Clarendon “is being altered into smaller suites.”

The chopping up of sprawling turn of the century apartments was rarely reversed. The former Hearst apartment, at least in part, would be an exception. In 1994 a project was initiated by architects Siris/Coombs to create a three-story penthouse for a new tenant (the building was converted to a co-op in 1985). Completed in 1997, the triplex includes 7,000 square feet of living space and 10,000 square feet of outdoor terrace space.

According to the Levine Builders’ website, interior finishes include “Venetian plastered walls and Brazilian mahogany wood floors; and Portuguese tiles and English “corkstone’ in the bathrooms.”

Real estate agents are wont to create romantic and often blatantly untrue stories around properties. The new penthouse got that treatment in spades. While admittedly some elements remain of the former space, including 15th century stained glass, it was routinely hawked as the former William Randolph Hearst apartment. It was also said to have had a rooftop skating rink used by Marion Davies. The concept of a skating rink is dubious enough; the thought that Millicent Hearst would allow the “other woman” into 137 Riverside Drive is outrageous.

The apartment was placed on the market in 2014 for $38 million; reduced to a more affordable $24 million the following year. It sold for $20 million in 2016.

The Clarendon’s more than 110 year history has seen the coming and going of noteworthy residents–many with remarkable stories. Yet none could compete with the Hearsts, whose larger-than-life drama played out in their larger-than-life home.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com