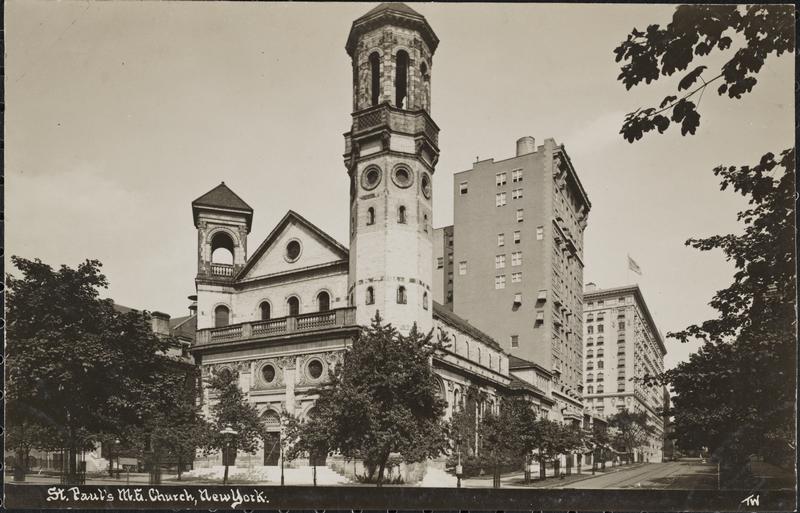

263 West 86th Street

St. Paul and St. Andrew Methodist Church

263 West 86th Street, aka 540 West End Avenue

by Tom Miller

A Happy Marriage of Styles

Many late 19th-century architects rightly felt themselves the heirs to all that had passed before them. That philosophy led to the design of structures described as a “happy marriage of styles.” And so it was with Robert H. Robertson’s St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church on West End Avenue at 86th Street. In 1895 St. Paul’s parish was already sixty-one years old, having been founded in 1834 in the then-residential Mulberry Street area near Bleecker Street. Progressive from its beginnings, it was only the second “pewed” Methodist church in New York City. Half a century later a writer for The New York Times would explain that “As such it naturally gained a certain amount of notoriety, ‘pews’ being then considered by the great mass of the Methodists in the light of an innovation, and as such to be resisted to the last extremity.”

Thirty-six years after moving northward to Fourth Avenue and East 22nd Street in 1857, the congregation decided to move one last time—now to the rapidly developing Upper West Side. St. Paul’s white marble church building on East 22nd Street was “known for many years…as the most expensive Methodist Church edifice in the city,” according to The New York Times. The congregation sold it in 1893 for $304,000 and held services for a time in the chapel of the Methodist Book Concern on Fifth Avenue at 20th Street, along what was called “Pater Noster Row,” while its next move was discussed.

On May 12, 1894, the purchase of seven lots on West End Avenue for $125,000 was announced, along with plans for a “new church, schoolroom, and parsonage.” Robertson stepped away from the Romanesque Revival style he had so successfully embraced in the 1880s, and dipped into an array of historic periods to create what was undeniably a “happy marriage of styles.” Construction on the new church began in 1895 and the ambitious project was not completed until two years later. Inside the cornerstone, laid on June 27, 1895, were the 1857 cornerstone, a piece of marble from the old church, and various contemporary documents.

Inside the cornerstone, laid on June 27, 1895, were the 1857 cornerstone, a piece of marble from the old church, and various contemporary documents.

Steeples tower above rowhouses

Working in buff-colored brick and terra cotta, Robertson used the barn-like prototype of an early Christian basilica as his central structure. To it, he added a soaring octagonal bell tower, inspired by German Romanesque churches, with Renaissance balconies at the belfry and deeply-framed roundel window. At the opposite corner a shorter, square tower sat askew, and in between an Italian Renaissance entrance porch with arched openings and magnificent Corinthian pilasters completed the design. (To add to the mix, The New York Times remarked that “The style is an outgrowth of a study in the Spanish Renaissance.”)

Inside, “the audience room is of octagonal shape with unequal sides,” wrote The New York Times. “There is a gallery on three sides, and the walls above the galleries are supported on a series of arches. The ceiling is an elliptical dome, with panel ornamentation.” The church finished at a cost of $300,000, was designed to seat 1,200 worshipers. Dedication services extended throughout the last week of September 1897. The New York Times reported that at the October 3 service, “over 800 people sat, closely attentive throughout the long service, which was not concluded until 2 o’clock.”

The imposing church with its tall tower dominated the residential area, causing Bishop Foster to comment in World Wide Missions that it was “without a peer among the church edifices of Methodism.” St. Paul’s was not the only Methodist church in the Upper West Side. Seven years earlier St. Andrews Methodist Episcopal Church had been completed, a hulking Romanesque Revival style building on West 76th Street, and as St. Paul’s was being completed, Grace Methodist opened in 1896 on West 104th Street. But while row houses were being built at a phenomenal rate and development of the neighborhood seemed unstoppable, eventually it would become evident that there were not enough Methodists in the area to fill these grand buildings.

Progressing towards progressive ideas

Not everything associated with St. Paul’s would be as progressive as the concept of pews. On April 3, 1927, the Rev. Dr. Clarence True Wilson of Washington D.C., “the leader of the Methodist dry forces,” addressed the congregation. Wilson, who carried the ponderous title of “General Secretary of the Board of Temperance, Prohibition and Public Morals of the Methodist Church,” predicted the end of “liquor traffic.”

There will never be a line dropped from the Eighteenth Amendment or the Volstead Act as long as there is a United States of America,” said the reverend. “We have got only about six Senators down there in Washington who are wet. But they make noise enough for sixty…Of the last group of wet Senators that were down there, do you know what became of every one of them? Every one of them was defeated and left at home.

The Twenty-first Amendment repealed the Eighteenth Amendment on December 5, 1933.

By 1937 the over-optimistic building of the Methodist churches on the Upper West Side was painfully evident and on November 7 Bishop Francis J. McConnell announced the merger of St. Andrew’s Methodist Episcopal Church with St. Paul’s – resulting in the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew. St. Andrew’s building was sold to the West Side Institutional Synagogue.

Not everything associated with St. Paul’s would be as progressive as the concept of pews.

Robertson’s exceptional building survives essentially unchanged, what the AIA Guide to New York City calls “a startling work” and the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission calls “masterful.” In designating the structure, a landmark in 1981, the Commission noted, “St. Paul’s is among Robertson’s finest buildings and one of the most powerful and original statements of its period.”

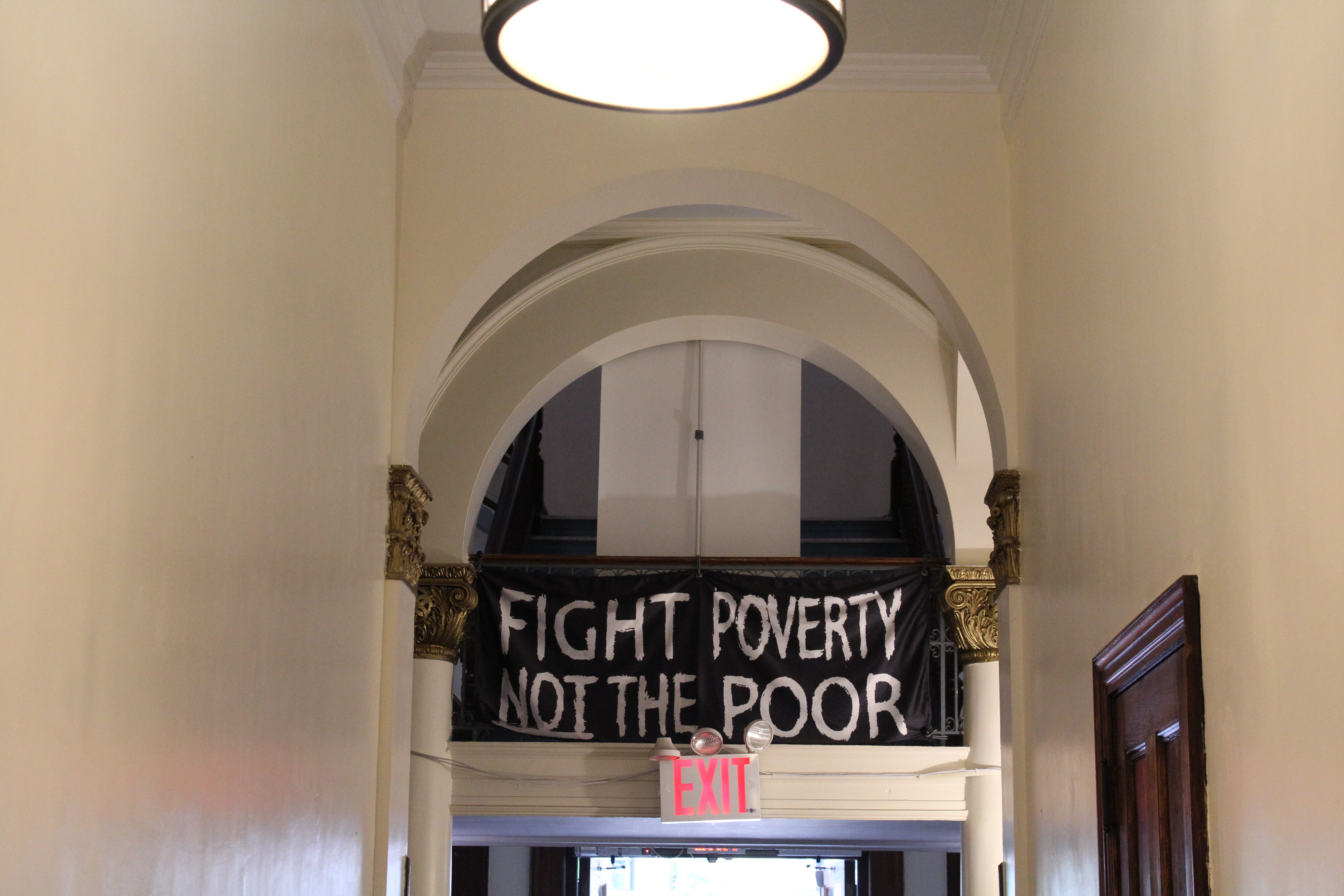

Along with worship, St Paul and St Andrews Church house the West Side Campaign Against Hunger initiative to provide an emergency food pantry and countless other necessary resources to fulfill people’s immediate needs. The sanctuary provides a unique space for performances, including their West End Theatre.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Return to West End Avenue

Landmarks Timeline

Building Database

Designation Report

Be a part of history!

Learn more about St Paul & St Andrew Methodist Church:

Meet Rev. K Karpen!