St Michael’s Episcopal Church

201-225 West 99th Street

by Tom Miller

As the 18th century turned into the 19th, St. Mark’s in the Bowery was the northernmost church in Manhattan. Not until the traveler reached Yonkers would he find another place of worship. It was a problem for wealthy New Yorkers who dotted the upper island with their grand and extensive country estates.

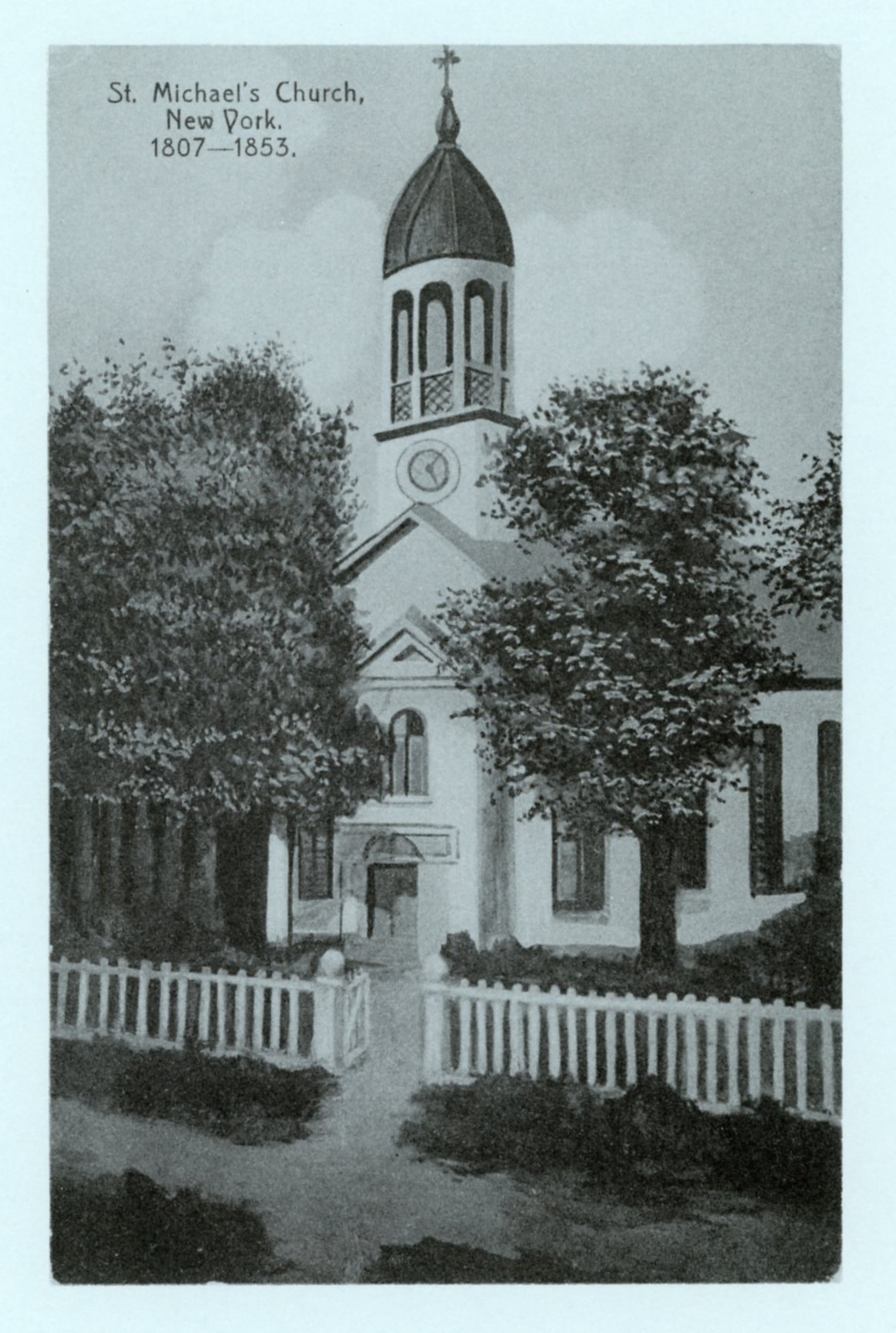

In 1806, several gentlemen, most of whom worshiped at Trinity Church, laid plans to build an Episcopal church in the country. Oliver H. Hicks donated the site and Trinity Church promised financial aid. On July 27, 1807, Bishop Moore consecrated the completed building at what today is Amsterdam Avenue and 99th Street.

An early watercolor depicts a charming rural church. Wooden and painted white, it featured the open belfry, grassy lawn, and picket fence expected in a countryside church erected by well-to-do families. The list of members included New York’s most prominent families: Elizabeth Hamilton, widow of Alexander Hamilton; the Schermerhorns, the De Peysters, the Schieffelin, and the Lawrence families among them.

The little church may have appeared quaint, yet it was anything but inexpensive. The cost of the first St. Michael’s was $4,959.72 (around $90,000 today) of which Trinity Church gave $2,000. The first pew rents were around $200 per year (about $3,500). Money was apparently not a great problem for St. Michael’s and in 1827 it was resolved to discontinue the morning and evening collections “as interrupting the solemnity of divine worship and generally unpleasant to the congregation.”

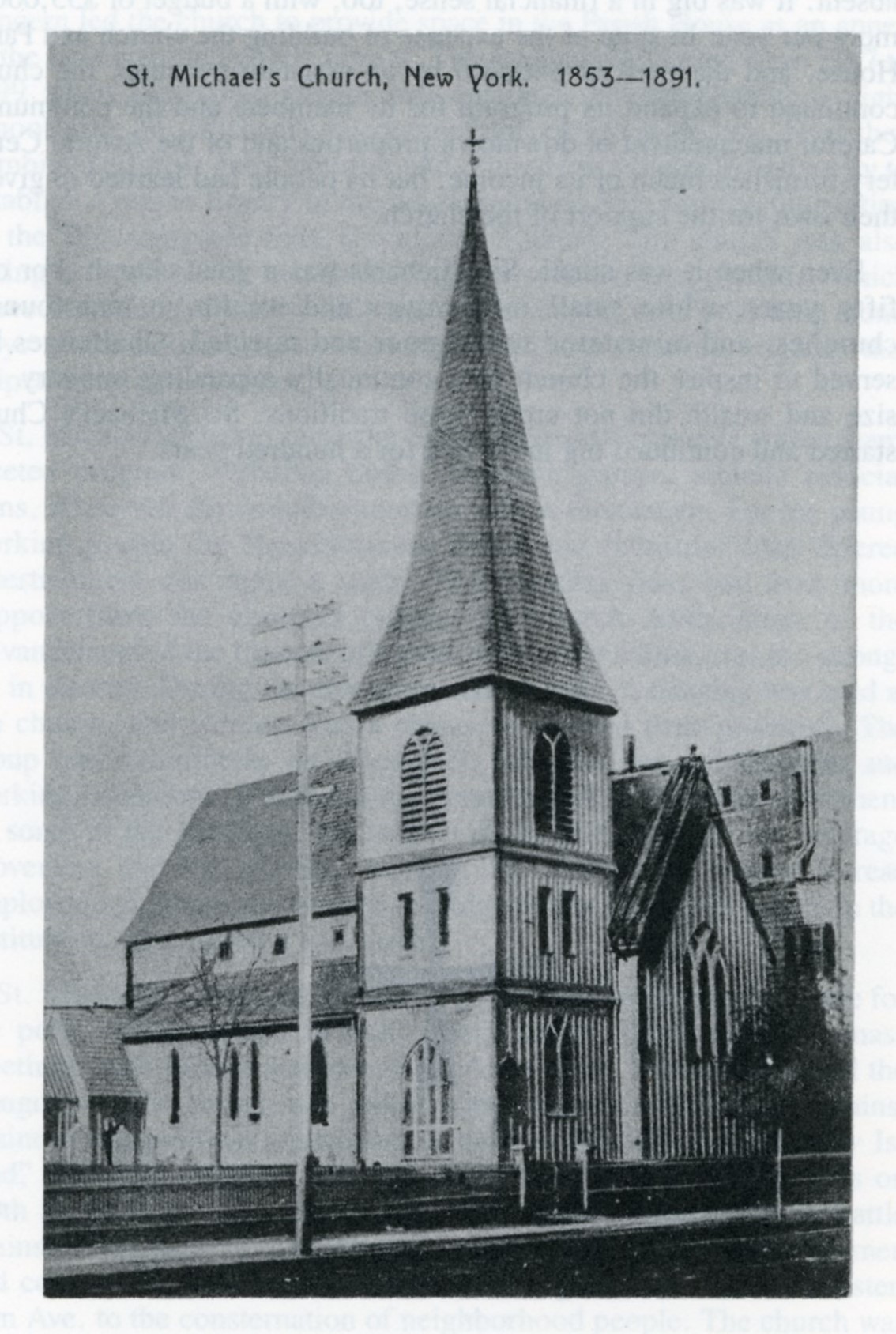

In 1853, the pew rents were abolished altogether. The same year the wooden church building was destroyed by fire. A second building costing $12,611.70 was quickly built on the same site—also of wood and slightly larger. The new church could seat 400, double the number of worshipers as the former church.

In the meantime, the neighborhood was experiencing more development. In 1859, there had been 21 baptisms at St. Michaels, and in 1863, there were 199. In 1864, gas lighting was introduced and the rector’s salary was increased to $3,500 due to the “increased cost of living.”

When the Civil War broke out, St. Michael’s was shuttered and locked, not to be reopened until the end of the conflict. The work of the church, however, continued through outreach programs and work with the needy and sick. St. Michael’s was the first church to provide Christian burial for the poor and its Charity School became the first public school on the West Side of Manhattan. The Churchman, in 1907, would remember “The work of the Church among the miserable and abandoned in the hospitals, the almshouses, the asylums and the prisons of New York, the work of the Church in the slums, the rescue for the fallen women, and forsaken children, all of these began in St. Michael’s.”

King’s Handbook of New York City called the new building “a noteworthy instance of modern intelligent ecclesiastical architecture.”

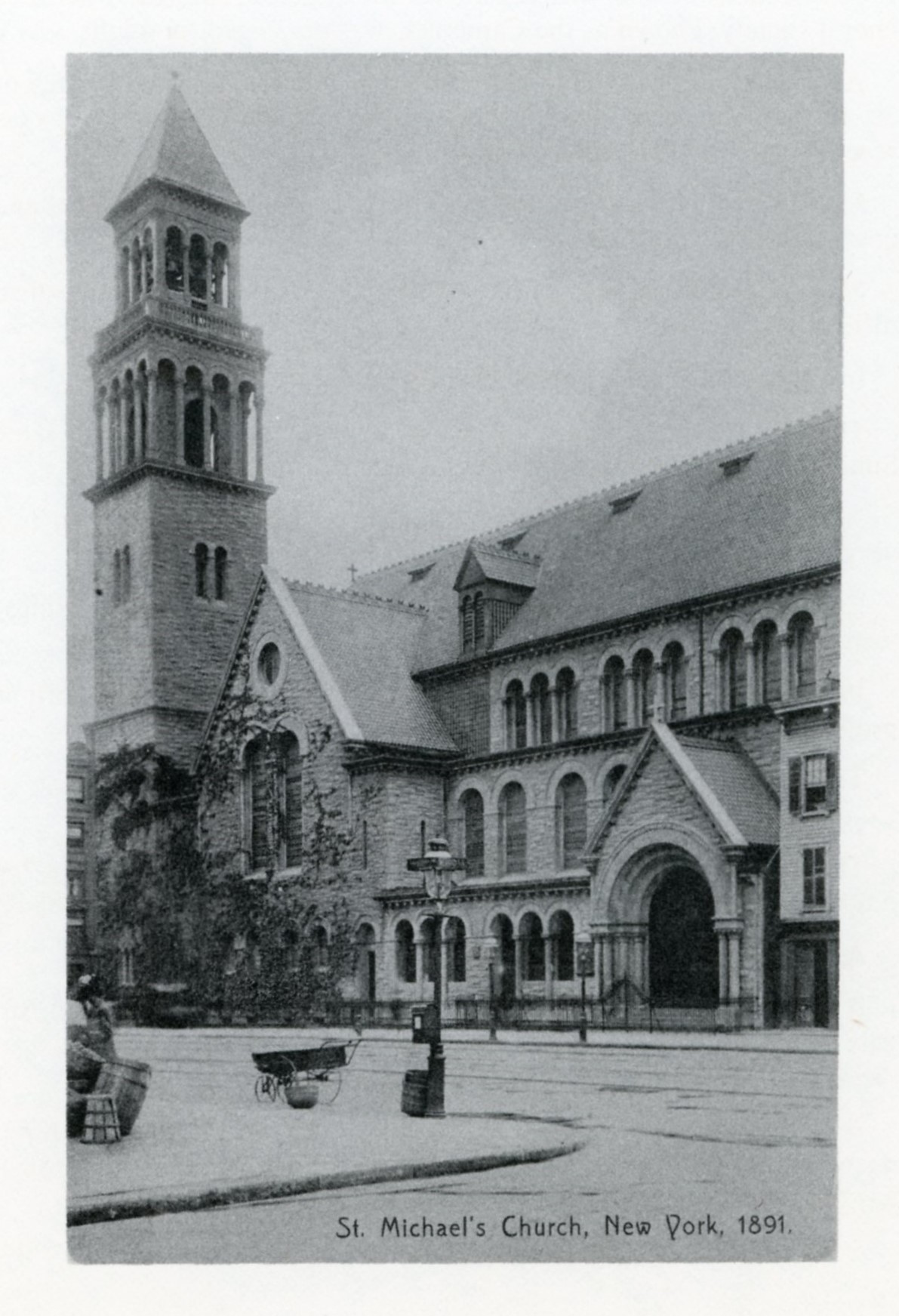

As the century drew to a close, Amsterdam Avenue had become a major thoroughfare and the Upper West Side experienced an explosion of new homes and businesses. The arrival of the elevated railway in 1879 made the area conveniently accessible. By 1889, a new church building was imperative. Robert W. Gibson was awarded the commission for the structure and he delivered a surprising yet remarkable design.

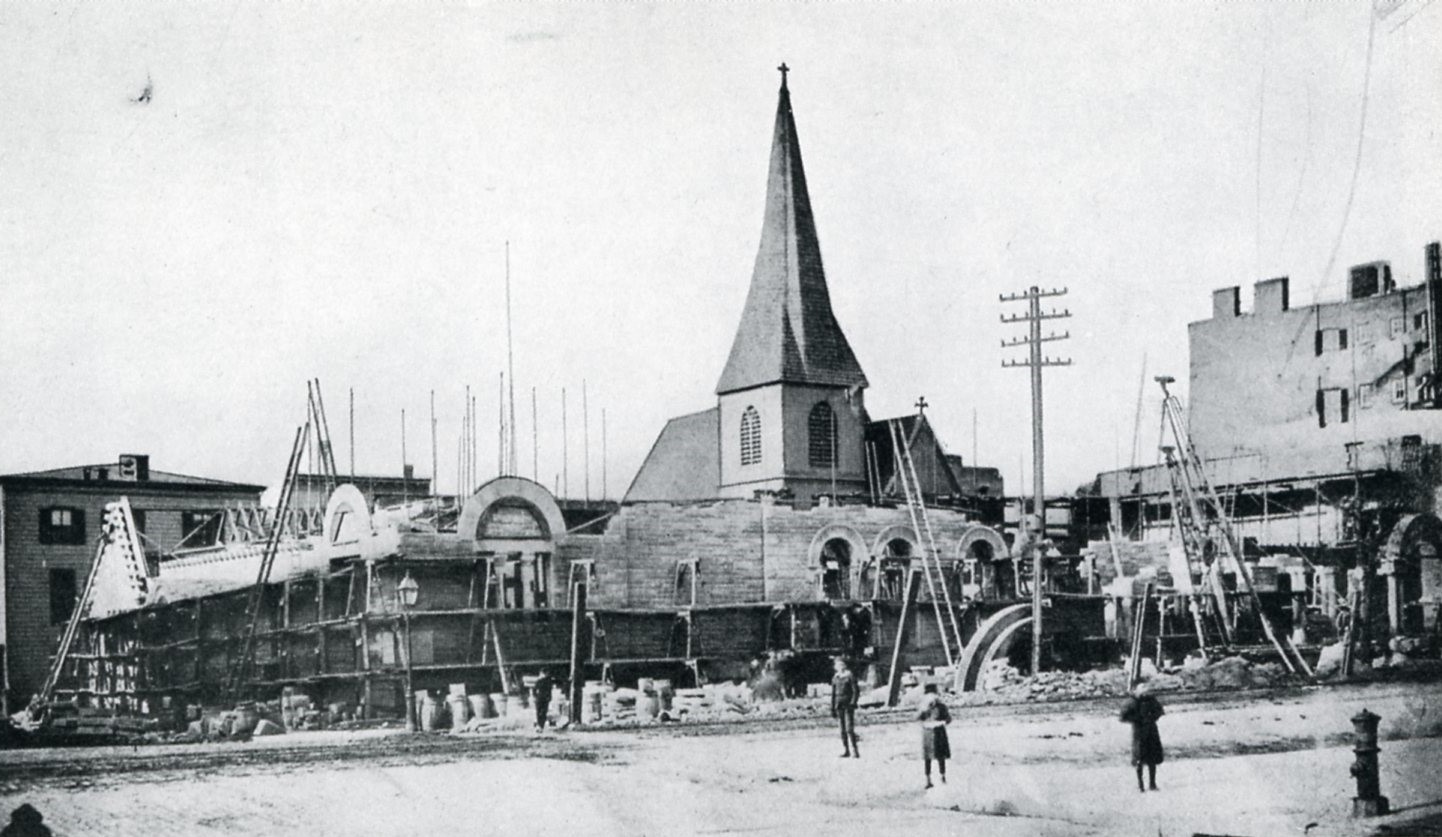

The cornerstone was laid by Bishop Potter on St. Michael’s Day, September 29, 1890. The walls began rising around the still-standing older church over the old cemetery. The day after the cornerstone laying, The New York Times noted that “In the excavations for the foundations a number of old vaults have been brought to light. The doors of three of these were to be seen yesterday in a bank of earth just back of the platform surrounding the cornerstone. It is intended to preserve these vaults, it was said yesterday, and to build the church over them.”

The building was expected to be completed in September 1891, however, that date came and went and work dragged on. Finally, on December 15 the still-unfinished church was consecrated. The New York Times remarked on the status of construction. “While the church was still far from being complete, the rood-screen not being in place for the consecration services, the pulpit, lectern, and altar being but temporary structures, the organ being only partially finished, the walls undecorated, and the windows wanting in memorial gifts, sufficient was nevertheless disclosed to make it assured that the new Saint Michael’s…will eventually be one of the finest houses of worship in this vicinity, if not in the country.”

Clad overall in rough-cut Indiana limestone it harmoniously combined historic styles. The Romanesque Revival, bowed chancel section on 99th Street nestles against a soaring Florentine campanile 160 feet tall. Unlike nearly every other Romanesque building of the time, which was built of brownstone or red brick, St. Michael’s gleamed in its white stone. When completed at a cost of $183,000 including furnishings the church could seat up to 1,600.

King’s Handbook of New York City called the new building “a noteworthy instance of modern intelligent ecclesiastical architecture.”

The “walls undecorated,” that The Times made mention of, would be worth the wait. Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company was given the job of decorating the interior and the project would be a long one. Between 1893 and 1907 the firm headed by Louis Comfort Tiffany lavished the chancel area with mosaics, a Vermont marble altar, the pulpit, altar rail, and glass reredos.

The magnificent chancel window in seven sections, each twenty-five feet high, depicted “St. Michael and all the Host of Heaven.” Executed by Tiffany artisans Edward P. Sperry, Joseph Lauber, Louise J. Lederle, and Clara W. Parrish, Palette; Bench magazine termed the group “the most important window in the country.”

However, Tiffany’s work ground to a halt, and the main sanctuary was left unadorned. In 1922 the firm was called back to decorate the Chapel of the Angels. A large mosaic mural behind the chapel altar was installed, as well as two additional stained glass windows. It was the end of Tiffany’s work at St. Michael’s, leaving the drab main sanctuary in marked contrast to the vivid Tiffany sections.

The Upper West Side continued to grow and in 1899, the Third Avenue Railway Company began plans to lay train tracks up the center of Amsterdam Avenue alongside an already-existing set. Pastor Dr. John P. Peters would not have it.

Peters raised money and recruited what The Outlook magazine termed “a few conscientious anti-monopolists” in a lawsuit against the railroad. The magazine insisted, “New York City has not in years been so stirred by an anti-corporation campaign as by the present one.” Peters intended to fight against “turning the attractive street into a dangerous car-yard.”

In March 1899, the Supreme Court of New York heard the case of “The St. Michael’s Protestant Episcopal Church in the City of New York, Plaintiff, v. The Forty-Second Street, Manhattanville and St. Nicholas Avenue Railway Co., Defendant.” The feisty preacher won.

One of the wealthy parishioners of St. Michael’s in the first years of the 20th century was Margaret E. Zimmerman. The widow of John E. Zimmerman and an heiress in her own right –her father William Ponsonby Furniss was known as the “West Indian merchant prince”–she had a falling out with her family.

When Margaret’s father died in 1871 he left his three sons and three daughters his fortune, including over 200 undeveloped lots in the Riverside Drive area. By the early 20th century that land was highly valuable as mansions began rising along the newly finished Riverside Park. In 1916 only the 84-year-old Margaret, now an invalid, remained alive among the heirs, having inherited their shares as each died.

When relatives insisted on an accounting of the original trust funds, the referee concluded that Margaret’s sisters had made unauthorized investments under the law and charged Margaret $257,838 in fines.

Margaret Zimmerman was not pleased.

When the rich woman died in her apartment at 400 Park Avenue in 1918, her relatives discovered they had all been ignored in her will. Instead, the Metropolitan Museum of Art received the valuable paintings and works of art, charities were given hefty amounts of money and St. Michael’s Church received more than $1 million in real estate and $50,000 in cash.

The money, no doubt, made Tiffany’s decoration of the Chapel of the Angels less burdensome.

On November 10, 1921, the Rev. Dr. John Punnett Peters died of a heart attack. Although he was noted as a civic reformer (not only had he battled the Amsterdam Avenue train tracks, he was Chairman of the Committee for the Extension of Transfers on Street Car lines and the President of the Transit Reform Committee of One Hundred and a crusader against “commercialized vice”) he was much more.

In addition to heading St. Michael’s Church, he had been a noted archaeologist, Hebrew scholar, and expert on Babylonian excavations. It was Dr. Peters who discovered and excavated the ancient city of Nippur and led the first archaeological expedition of the University of Pennsylvania to Babylonia.

In March 1899, the Supreme Court of New York heard the case of “The St. Michael’s Protestant Episcopal Church in the City of New York, Plaintiff, v. The Forty-Second Street, Manhattanville and St. Nicholas Avenue Railway Co., Defendant.”

After nearly a century of use, St. Michael’s Church embarked on a three-year restoration in 1989. Nicholson & Galloway, Inc. cleaned and repointed 20,000 square feet of the limestone façade. The church bells and the timber supports of the belfry were removed and restored. The entire Spanish tiled roof was removed and 18,000 square feet of original tile was replaced with matching Ludowici clay tiles.

But inside something daring was going on. Fine Art Decorating of Manhattan restored the Tiffany interiors and then went a step further. Because plans for the rest of the church were never completed by Tiffany, the firm carefully designed decorations in the Tiffany spirit.

Costing over half a million dollars, the result is dazzling. The sanctuary that for nearly a century had moped in drab neutral colors now exploded in vivid primary colors with gold accents. The entire space was now cohesive, perhaps as the renowned decorating firm had originally envisioned.

St. Michael’s Church was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and the New York State Register of Historic Places in 1997.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com