St. Agnes Chapel

121-147 West 91st Street

by Tom Miller

Ten years before the American Revolution, Trinity Church recognized a problem. The city was expanding northward, and as parishioners moved further away from the church, attending services was inconvenient. In 1766, St. Paul’s Chapel was opened, a “chapel-of-ease.” By 1807, when St. John’s Chapel was erected on the elegant and exclusive St. John’s Park, the term most often used was “chapel of convenience.”

The trend would continue throughout the century as the city crept further and further northward. With the completion of Central Park and the opening of the Ninth Avenue elevated train in the 1870s, the Upper West Side experienced a flurry of development. Wealthy merchant-class parishioners settled into broad brownstone homes. Before long, Trinity Church would need another chapel—its fourth.

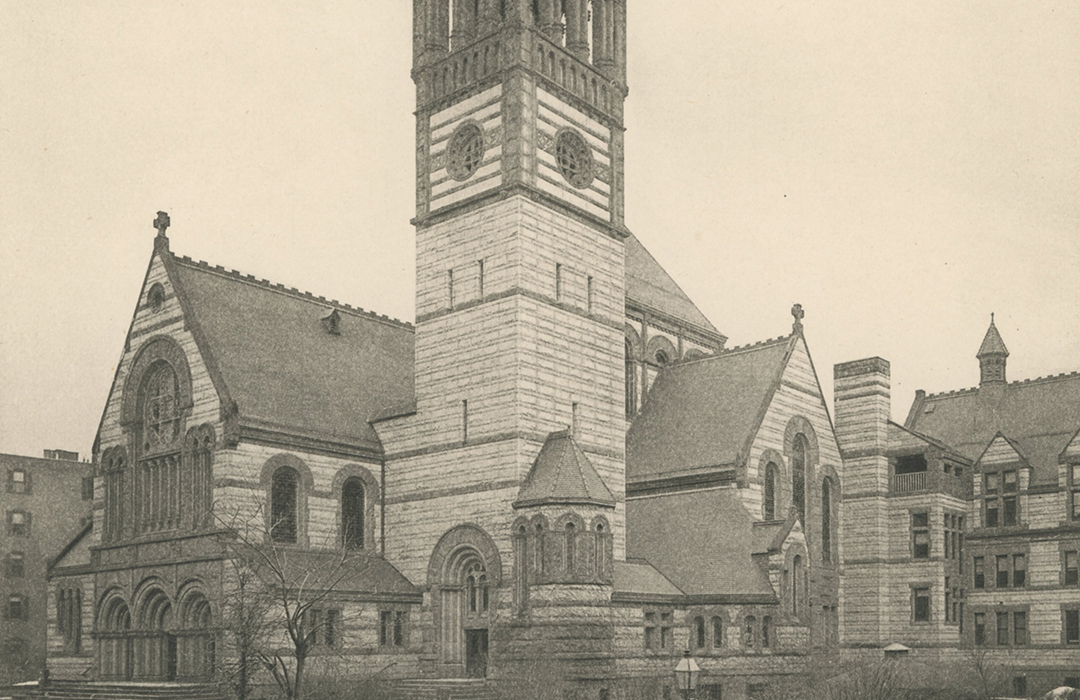

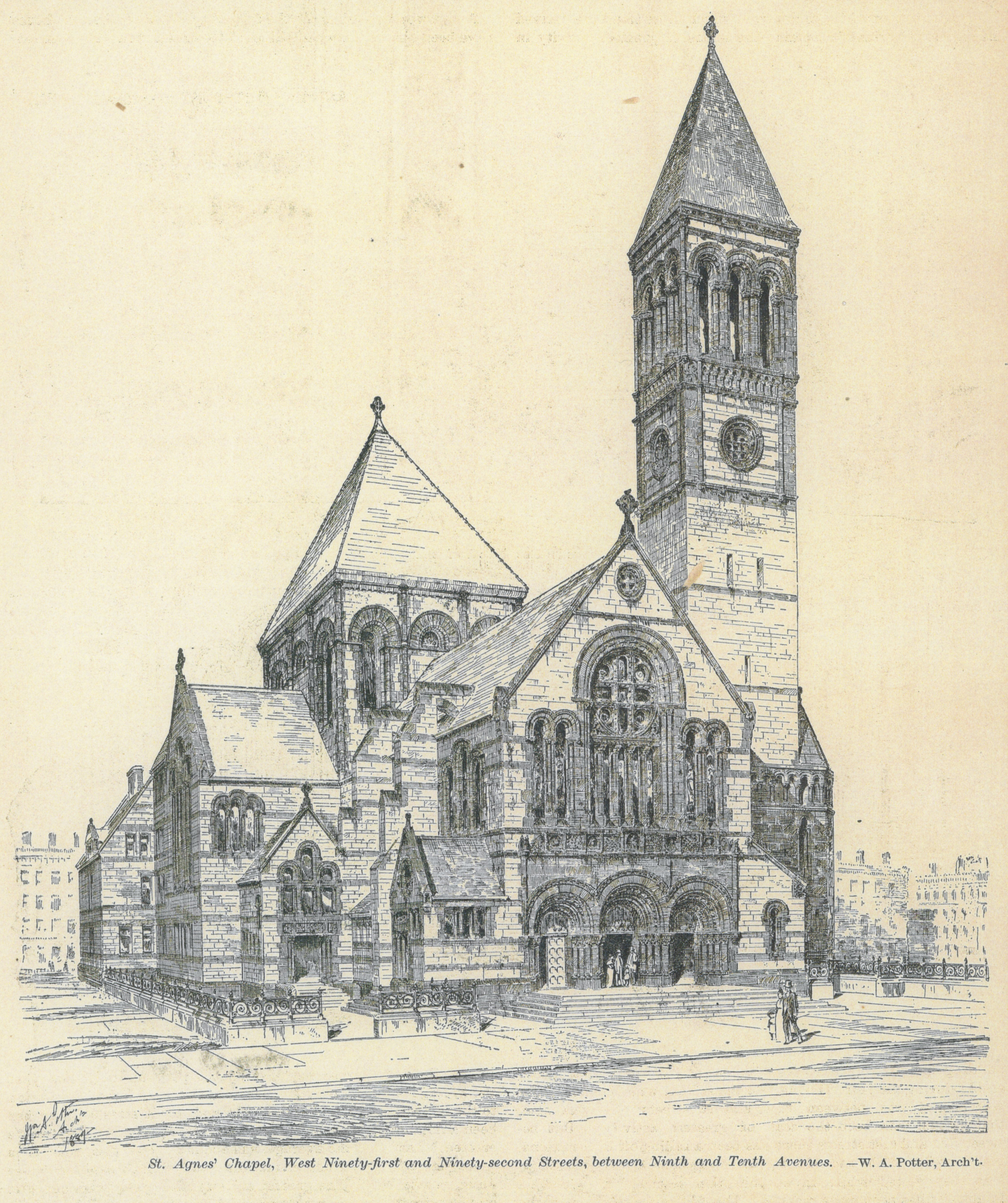

Twenty plots of land were purchased on West 91st Street through to 92nd Street between Ninth and Tenth Avenues. Architect William Appleton Potter was commissioned to design a suite of buildings—a church, a morning chapel, a parish house, and a rectory. The New York Times cautioned readers about interpreting the term “chapel” as “small.” “The term chapel is only employed because St. Agnes is a part of Trinity Parish.”

In fact, like Trinity’s other chapels—St. John’s, St. Paul’s, and Trinity Chapel—it would be an impressive and splendid ecclesiastical structure. The Architectural Record would point out, “The Romanesque had by this time succeeded the Gothic fashion, and Mr. William Appleton Potter had addicted himself to the Richardsonian phase of Romanesque with enthusiasm.” With his design for St. Agnes Chapel, Potter would bring Romanesque to a level unseen to date in Manhattan.

On May 19, 1890, the cornerstone was laid with a ceremony that The New York Times deemed “unusually impressive.” Bishop Henry Codman Potter (coincidentally or not, the architect’s brother) oversaw the procedure that included a procession up Tenth Avenue, which had been closed for the occasion. If 1,000 onlookers needed a hint as to the grand chapel that would rise here, they needed only to notice the tools used in the laying of the cornerstone.

The New York Times reported, “The trowel which was used was made of silver, the square was of rosewood, with silver ornaments, and the mallet was of boxwood, with a carved ivory handle ornamented at the end with a silver cross.”

A year and a half later, as construction continued, The New York Times remarked, “St. Agnes is not only the latest undertaking in the line of chapels on the part of Trinity, but it is the most costly of the several auxiliary church enterprises.” The newspaper estimated the final cost at just under $1 million.

The New York Times cautioned readers about interpreting the term “chapel” as “small.”

On April 23, 1892, the structure was nearly completed. The Times was taken with Potter’s results. “St. Agnes is not only the finest church edifice under the jurisdiction of Trinity Parish, but the finest church structure, barring the cathedral, in New-York City. It is, perhaps, the most perfectly-equipped structure for religious work of all sorts in the United States.” Dr. Nevin, the rector of the American Church at Rome, pronounced the Romanesque building “the finest example of that style of architecture” he had ever seen and the Architectural Record called it, “the most important, as well as most costly and pretentious of the churches with which [Potter] adorned Manhattan under this influence.”

The completed church would stretch 174 feet from front to back—40 feet longer than Trinity Church. The chancel, 63 feet long and 38 feet wide, was “with the exception of those of cathedrals,” the largest in the country, according to The Times.

The choir rail, Bishop’s throne, baptistery, and reading desk were of white marble, with royal green marble panels and glass mosaics. Seven marble stairs led to the pulpit, and another seven steps led to the white marble altar, “the top step being almost on a level with the gallery over the main entrance.”

Long Meadow brownstone, the same as used in the exterior, formed the lower section of the chancel walls. Blue glass mosaic panels were inset into the brownstone, interspersed with gilt columns. The glass mosaics continued around the cancels and between the windows. Oil paintings on canvas, imitating mosaics and representing twelve apostles and the seated Christ, were installed above a belt of stone. The New York Times noted, “At the end of the lines of the Apostles’ figures are double panels, on which are painted gorgeously-plumed peacocks.”

The newspaper continued, “The arch of the ceiling is laid in gold and incrustations in imitation of jewels. The effect is like that of the interior of an Oriental mosque.” The cavernous interior held two pipe organs, and the mosaic floor was imported from Europe. It could comfortably accommodate 1,400 worshipers.

The exterior was composed of brownish-spotted granite with brownstone trim. Commanding attention was the tall bell tower, or campanile, which rose 185 feet above the morning chapel. Inside was a “Westminster peal” of four immense bronze bells, the largest of which weighed nearly four tons. A 40-foot square central tower, 100 feet high, capped the intersection of the nave and transept.

The other buildings blended harmoniously with the church. The clergy house contained 20 large rooms. “It is of the most modern interior architecture,” said The New York Times, “and finished in ash throughout.” The parish house accommodated the Sunday school on the third floor, capable of seating 600 persons. The morning chapel, decorated to match the interior of the main chapel, would seat about 150.

Seventeen years later, the Architectural Record would still praise the buildings saying, “It is not only an excellent example of a fashion which has passed. It is one of the examples which makes it seem rather a pity that it was a fashion only, and that it has passed.”

As Trinity Church prepared for the consecration of the new chapel, it took steps to make the music of St. Agnes unsurpassed. G. Edward Stubbs was hired away from St. James Church on Madison Avenue and 72nd Street. “Mr. Stubbs is well and favorably known as a specialist in the training and direction of boys choirs…His success in the musical field has been pronounced, and he has latterly had charge of the training of the celebrated choir of male voices at the General Theological Seminary,” remarked The Times.

The consecration, which took place on September 27, 1892, was “accomplished without the slightest friction,” according to the press. In the procession of over 200 persons were four Bishops and 132 priests. Stubbs’ 40-member male choir impressed. The New York Times said, “It is seldom that so beautiful a body of boys’ voices is heard in the churches of this city.”

The New-York Tribune commended, “The somber decorations of the nave contrast sharply with the brilliancy of the altar and the chancel.” The “brilliancy” was in part due to the communion and altarpieces made by Gorham Manufacturing Company. Two communion sets were of solid silver, and two matching sets were bronze. The silver services consisted of ten pieces each—a flagon, a ciborium, two plates, a chalice spoon, three glass cruets, and two chalices—weighing a total of 530 ounces.

On the altar was a bronze cross, said to be among the largest Romanesque crosses ever cast. In addition, there were two “large and elaborate” bronze candlesticks, three feet high, and two bronze vases 16 inches high. The cost of the altarpieces was $5,500—approximately $150,000 by today’s standards.

By the turn of the century, St. Agnes membership had soared to over 2,000 persons. It was the scene of high-profile funerals and weddings. Here, on the afternoon of November 29, 1904, was the wedding of Arthur Iselin and Eleanor Jay. Bishop Potter pronounced the benediction to the assembled guests that included Fishes, Belmonts, Mackays, Sloanes, Vanderbilts, Burdens, de Peysters, Schermerhorns, Astors, Morgans, Goelets, and Harrimans, among others—in short, every important name of Manhattan’s elite social list.

When Armitage Mathews fell from a window in October a year later, his low-keyed funeral at St. Agnes was attended by hundreds of preeminent military, business, and political figures. The New-York Tribune reported that the coffin was “viewed by thousands of people, among whom were many women.” Among those in attendance was the Attorney General, Congressman W. S. Bennet, Senator Page, Justice Seaman, several judges, and “every Republican leader in the city.”

Among the most exciting members of the parish was Mrs. John Alden Gaylord. Born in Zurich, she traveled to New Orleans at the age of 16 to live with a wealthy uncle. Described as “a blonde beauty,” Eugenia met the Count de Cenola and three months later was married in Paris. Just a year and a half later, the Count died, and the teenage widow returned to the United States, where she married the stock broker Gaylord.

Gaylord was a direct descendant of John and Priscilla Alden of the Plymouth colony, and the new Mrs. Gaylord became prominent as a hostess in the 1880s and 1890s in her mansion on Fifth Avenue and 46th Street. The New York Times would later remember that she “once entertained six famous Generals in her home.”

As the Upper West Side became increasingly fashionable, the Gaylords moved into an impressive Riverside Drive residence and began attending St. Agnes. Eugenia was interested in the financial affairs of her husband and assisted him in his brokerage office—a highly unusual pastime for a socialite.

During the summer of 1944, William Appleton Potter’s magnificent Romanesque trio was bulldozed with little being salvaged.

When John Alden Gaylord died, Eugenia took up his business, working shoulder-to-shoulder with the likes of George M. Pullman and C. P. Huntington. The Times noted, “Her offices were always the scene of short church services in the morning and the hall leading to her quarters came to be known by others in the building as ‘Church Row.’”

Then came the Financial Panic of 1907. Eugenia Gaylord, once a society belle of New Orleans and Paris, was wiped out. For the next twenty years, she relied on help from friends and former business associates of her husband. Then she disappeared.

A reporter for The New York Times, scouting out charity cases for the newspaper’s “Hundred Neediest Cases of The New York Times,” stumbled across the woman “living in squalid surroundings in a crowded street of one of the poorer sections of Brooklyn.”

The newspaper published her predicament, asking for hand-outs. Although money was donated, welfare organizations were frustrated, “as she refused to stay in homes to which she was sent. She was supported by friends until she ‘no longer knew or cared where she lived,” said The Times.

She was sent to the Metropolitan Hospital on Welfare Island. Here she lived until the age of 83. “Her mind, once brilliant, dwelled continuously on the events of the ‘90s,” lamented The New York Times.

Eugenia Gaylord, once the Countess de Cenola, died of pneumonia in the charity hospital in October, 1931. Her funeral was held in St. Agnes, paid for by the rector. “A small group of friends who knew Mrs. Gaylord in her days of beauty and wealth attended the services. Beautiful floral sprays, a tribute of friends and the church covered the coffin.” Thomas E. Browne, the sexton, spoke of her as a “dear old soul.”

In 1942, the stained glass windows were removed and replaced with plate glass to safeguard them “against possible air raid damage,” according to the Rev. Dr. Frederick S. Fleming, rector of Trinity Church. By then, the population of the Upper West Side was made up of more Roman Catholics and Jews than Episcopalians. St. Agnes was in trouble financially. Trinity Parish embarked on a “streamlining” process to divest itself of underutilized real estate.

Next door to St. Agnes was the venerable Trinity School, a private institution for boys. Unlike the chapel, the school was doing just fine. In 1942, the school offered the parish $50,000 for the group of buildings—which had cost just under $1 million half a century earlier.

The transfer of the property to Trinity School was announced on June 10, 1943, and the Rev. Dr. Frederic S. Fleming, rector of Trinity Parish, told the press, “Now…Trinity School will be enabled by the additional property to provide more adequately for its rapidly growing enrollment and activities.” The school immediately sold off everything in the buildings—the high altar, the bronze bells, the stained glass and organs, even the hymnals.

During the summer of 1944, William Appleton Potter’s magnificent Romanesque trio was bulldozed, and little was salvaged. The European mosaic floors were crushed to provide landfill for the site.

The purpose for which the school needed “to provide more adequately” for its enrollment became evident. Where St. Agnes Chapel had stood, a baseball field was installed.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com