The Locomobile Building

by Tom Miller

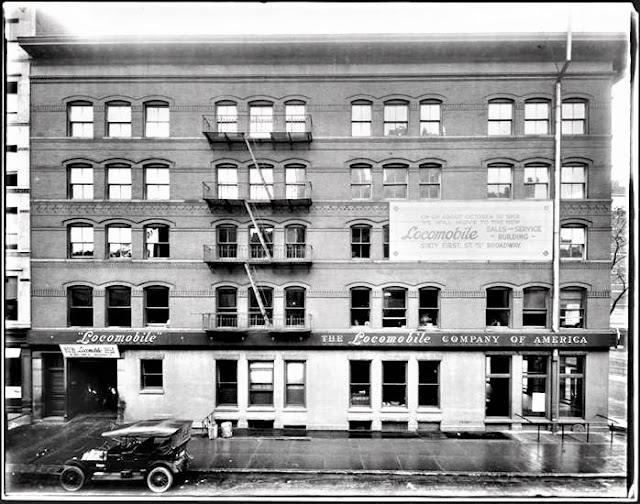

Founded in 1899, the Locomobile Company of America produced steam-driven cars in its Bridgeport, Connecticut facility until 1903. That year the firm switched its entire production to internal combustion powered, high-end automobiles. Its New York City offices and showrooms had been located at Broadway and 76th Street since its inception.

But by 1912 space in that building had become unacceptably tight. On January 7 that year the New-York Tribune reported on an innovative scheme the firm had devised to address the space problem. “It has conceived the idea of constructing miniature models, painted in harmonious color combinations and made to exact scale, thus giving the true lines of the cars.” The scale models exhibited the paint variations and diverse models in a small area.

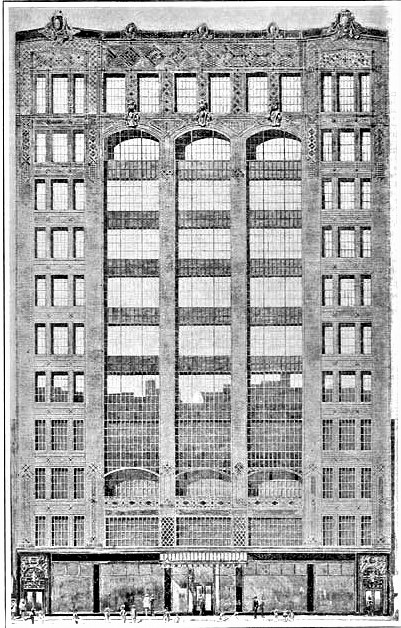

But that solution was merely temporary. The day before the Tribune’s article the Record & Guide had announced that the Locomobile Company of America had hired the architectural firm of Kirby & Petit to design an impressive structure for its headquarters, showroom, and automobile service department. It would replace the old houses at Nos. 16 through 24 West 61st Street, and the one directly behind at No. 25 West 60th Street.

But the Locomobile Company of America rethought the ambitious plan. A year later the project had still not moved forward and on February 1, 1913 the Record & Guide reported that the firm had sold the old buildings to developer R. E. Pinchot. “On the combined plot Mr. Pinchot will erect a 12-sty building and will lease it for 21 years to the selling company.” He had paid the Locomobile Company of America $300,000 for the property, and his architect, Walter Haefeli, estimated the cost of the building at another $400,000. That brought the total outlay for the project to $18.3 million in today’s dollars.

The building, reduced to eleven floors, was completed by the end of the year. And while it was admittedly not outwardly as architecturally striking as Kirby & Petit’s; Haefeli’s functional design and the location caught national attention within the automobile industry.

For one thing, the building did not sit directly on “Automobile Row.” Broadway north of Herald Square was lined with the headquarters of automobile-related firms. Automobile Topics explained on January 31, 1914 “Placed in this position, the branch is in very nearly the center of the automobile district of Broadway, but by being on a side street, the high rents of the famous thoroughfare are escaped. At the same time, nearly all the advantages of a Broadway location are secured.” The article continued “Due to the wideness of the angle with which Sixty-first street meets Broadway, the Locomobile building is in easy view from the latter street, and its pleasing front dressed with brown brick sets if off from all the surrounding structures.”

The street level on 61st Street was taken up by vast show windows. The Locomobile Company of America reserved six floors totaling 61,600 square feet for its own use, which left five floors for rental purposes.

It was the rear of the building that most impressed the auto industry. Where the old brownstone had stood was now a long drive, capable of accommodating two cars–one in either direction. It led to a large elevator which took vehicles to the Locomobile service department or to the floors of auto-related tenants.

The Automobile, on February 5, 1914, wrote “The main feature of the building, from a constructional point of view is the fact that the freight elevator is entirely outside the building…The elevator itself is one of the largest in the world.” It could carry, said the article, two automobiles at a time. The exterior elevator not only freed up floor space inside the building; but “saves all the space which is usually required for maneuvering cars in order to get them on the elevator.”

“Placed in this position, the branch is in very nearly the center of the automobile district of Broadway, but by being on a side street, the high rents of the famous thoroughfare are escaped…”

Automobile Topics explained “On driving his car on the elevator, the chauffeur leaves it, and walks through a short alley into the rear entrance of the station proper, passing by a checking room. He may then go to the floor above, to the offices of the service department proper, to make out his order sheet, telling what he wants to be done on the car.”

Automobile Topics was impressed that “Instead of leaving the chauffeur or owner to fill out his order blank unassisted, an inspector is assigned to him. He is met promptly on coming into the room by one of the clerks, who make it a special duty to see that everyone is promptly greeted and his business attended to.”

Repairing the automobiles sometimes required a blacksmith’s expertise. On the 11th floor was the “forge room” for just that purpose. Automobile Topics explained that New York Fire Department regulations forbade open fires within a building. But the architect had deftly side-stepped that restriction. “At the Locomobile station, however, by means of fire walls and an air well one corner of the eleventh floor has been so completely shut off from the rest of the building as to pass the fire inspectors. This means that it is possible for car parts that may need the application of a flame, as in welding, to be worked upon without removal from the car, and without taking the open flame into the station proper.”

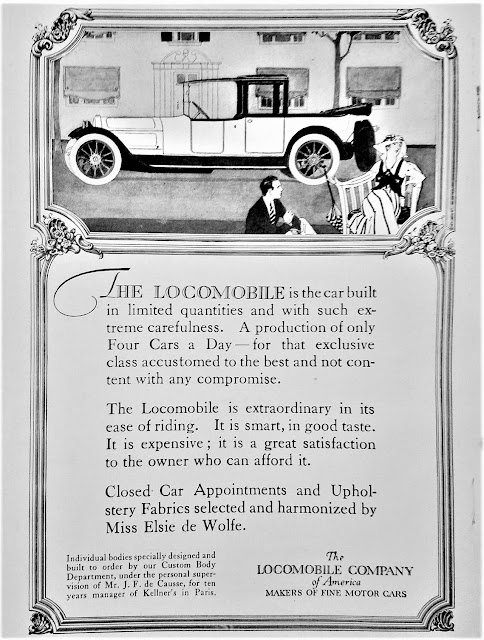

On announcing that the firm had moved into its new building, New York manager John F. Plummer reminded customers of the firm’s two mottoes: “Quality instead of Quantity” and “Service above Sales.” He added “Our manufacturing rule never to produce more than Four Cars a Day keeps the Locomobile demand and the Locomobile Supply in a perpetually safe ratio.”

The five rental floors filled quickly with automotive firms. On June 21, 1914 the New-York Tribune reported that the Marmon Company “has leased the entire eighth floor in the modern building at 16 to 24 West 61st st., and is fitting up one of the finest service departments to be found in the city…A fully equipped machine shop is in process of installation. It is to be fitted with everything necessary to turn out good automobile repair work, and the mechanics will all be men families with the Marmon car.”

Other tenants by 1915 were the Stevens-Durea automobile service department, the Franklin Auto Company, and the business office of John Philip Sousa, Jr.–the latter an exception to the automobile tenant list. Although the son of the famous bandleader was described in newspapers as a musician, he dabbled in real estate and other businesses.

The following year the Springfield Body Co. and the Redden Motor Truck Co. leased space. That same year Locomobile’s idea of building on the side street rather than on Broadway was copied by another major manufacturer. On December 9, 1916 the Record & Guide reported that the Packard Motor Car Company had paid $200,000 for the four-story apartment houses at Nos. 27 through 33 West 61st Street. The article noted “This recent purchase makes 61st street an important automobile side street, the Locomobile Company having their headquarters immediately opposite.”

John Philip Sousa, Jr. was heading home from the Locomobile Building on Thursday night, December 20, 1916, when he turned from businessman to hero. The New York Times reported, “When a woman screamed on Park Avenue, near Thirty-fourth Street, early last evening and said that a man had snatched her wristbag, John Philip Sousa, Jr. of 16 West Sixty-first Street, took up the chase and caught the fugitive on Thirty-fourth Street between Park and Madison Avenues. Sousa held his captive until a policeman arrived.”

Sousa appeared in General Sessions court on January 11, 1917. He identified Albert Steiger as the man whom he saw “waylay a woman on Park Avenue and steal a pocketbook from her.” The Evening World described Steiger as “a homeless wanderer” and said he pleaded guilty, saying only that “he was hungry and fell to temptation.” When Sousa realized the man’s plight, he offered to give him money, but the judge refused the gestured.

The building continued to lure automobile firms. In January 1918 the Franklin Motor Car expanded into another floor; Asch & Co., Inc., makers of auto accessories like automobile straps, funnels and measures, and auto buckets leased space in 1919; and the Lexington Motor Company took a floor that same year.

Also leasing space in the building in 1919 was the Allen Auto Specialty Company, headed by William A. Allen. Allen had invented a protective covering for tires which was sold world-wide. Another invention, the Shutter Front, helped prevent cold air from lowering the temperature of the radiator in winter months.

In 1919 The League for Motorists’ Protection had its headquarters in the building. On November 23, the New-York Tribune reported: “The league holds to the theory that any businessman who retains in his employ a chauffeur of proven recklessness is in some measure, at least, responsible in the event that chauffeur, through recklessness, injures or kills a pedestrian or an operator of another motor vehicle.”

William Allen was most likely on board with the League. Five months earlier The Sun had reported that Genji Kaneko, “a Japanese chauffeur, who for upward of ten years past has been employed by various wealthy families,” was “quite the heaviest batter in this speed league.” Already that year he had been involved in three collisions, two of them within only a few days of being hired by Mrs. A. W. Malley.

“On Wednesday he fouled a car owned by William A. Allen, president and treasurer of the Allen Auto Specialty Company of 16 West Sixty-first street, into the grass off the West Drive in Central Park…At the time of the collision with Mr. Allen’s car he had a maid and two children in the machine that he was driving.”

A Locomobile of America advertisement in the New-York Tribune on September 9, 1920 clearly indicated the expense of its luxury cars. It said that the firm 20-year old principle of design satisfied “the requirements of men and women to whom quality is essential and price immaterial.”

But the esteemed firm was in trouble. Earlier that year a full-page advertisement placed by Hare’s Motors in The Sun announced that the firm was now operating three makers, Locomobile, Mercer Motors Co., and Simplex Automobile Company, Inc. The following year, on July 22, Locomobile was acquired by Durant Motors. That firm would continue using the Locomobile brand name until 1929, when Locomobile ceased to exist.

The early 1920’s saw new tenants, including the Cole Motor Car Company, which took two floors in 1921, and the American Taximeter Company, which took one.

By the 1930s other industries were represented in the building. Although auto firms, like the Checker Cab Company, which ran its used car dealership here, continued to lease space, in 1931, sculptor and art instructor Alexander Archipenko had his studio in the building. On March 12 that year, The Kingston Daily Freeman reported, “Mr. Archipenko teaches sculpture, painting and drawing at his present art school, located at 16 West 61st street, New York city.”

Another unexpected tenant was the Needlework Guild of America. On November 3, 1933, The New York Times reported on its annual meeting, this one focusing on a clothing drive for the needy. “Around the walls of the loft were numbers of sacks filled with new garments which will be distributed among the 300 charitable organizations the guild has aided in the past.”

The building continued to lure automobile firms.

The Telautograph Company was here by 1935 when one of its employees, Jerry Kelly, got into serious trouble. When cab driver Morris Brayer stepped away from his taxi on December 10, Kelly jumped in a drove away. The Poughkeepsie Eagle-News reported, “Curiously Kelly was trapped through the medium of his own daily employment, the teletype system.” His description and that of the cab were sent off to police stations and he was quickly nabbed.

Other tenants in the building in the 1930s and ’40s included the Stutz New York Co., the Barclay Manufacturing Company, makers of “tileboards,” the Chevrolet Finance Outlet (where used Chevy’s were sold), and the Haver Company, distributors of automobile parts.

Like Locomobiles, the Stutz vehicles were not cheap. An advertisement in The New York Sun on July 28, 1931 announced “The New ‘DV-32’ Stutz,” a “straight-eight with thirty-two valves.” The prices began at $4,895–about $80,700 today.

On August 8, 1942, The New York Times ran a small headline reading “More Icebox Space” and announced that Nash-Kelvinator had taken space in the building. “The lessee will combine its automotive and refrigerator divisions into one large office, display room and parts warehouses.”

The Telautograph Company was still in the building at the time and would remain for at least another three years. In 1953 , Allen Auto Specialty Company was still here after at least 35 years when its founder, William A. Allen died in October. And Nash-Kelvinator, too, was still operating here.

Lehr Distributors, Inc., sellers of auto parts and electrical appliances, were in the building by 1958. Its 25-year old bookkeeper, Nancy Von Dolin, was arrested in June that year for embezzling nearly $13,000 over a period of time. Her finagling of the books was discovered when a customer was pressed for a $2,000 debt and provided a canceled check as proof of payment. Nancy had so far absconded around $113,000 in today’s money.

A renovation completed in 1974 resulted in a parking garage on the 60th Street side. Another, completed in 1986, converted the upper floors to offices and studios. And in then in 2008, a renovation was completed for the New York Institute of Technology, which now used the 6th through 10th floors as classrooms and part of the 11th as a lecture hall.

Rather surprisingly, throughout its long history and various uses, the exterior of the Locomobile Company Building has been only slightly altered; its handsome brick and limestone facade looks much as it did with wealthy car shoppers peered through the plate glass windows.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com