Hotel Empire

by Tom Miller

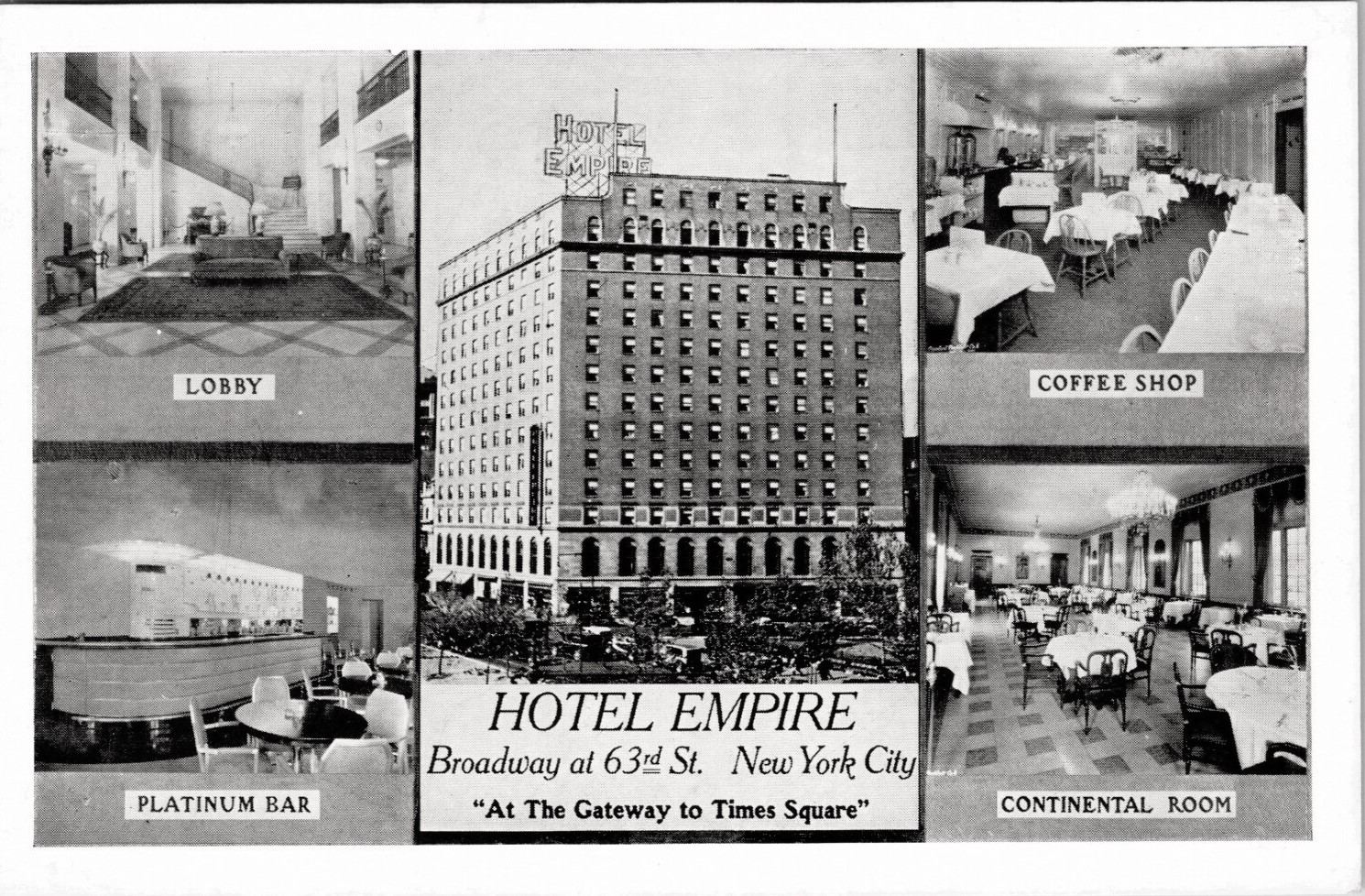

Prolific real estate developer William Noble was, no doubt, proud of his lavish Hotel Empire when it opened on September 25, 1894. The Evening World explained that it faced “on the little park at Grand Boulevard [later Broadway], Columbus avenue and Sixty-third street.” The sumptuous hotel took its name from the park, Empire Square, which would later be renamed Lincoln Square, and then Dante Park.

Unfortunately for Noble, his ambitious project was ahead of its time. While the Upper West Side was well developed by 1894, the need for transient hotels this far north was years away. He lost the property in foreclosure, after which the Hotel Empire changed hands repeatedly until 1908 when Philadelphia businessman Herbert Du Puy purchased it.

On April 15, 1922, two months after a sensational murder took place in the hotel, Du Puy announced plans for a 10-story addition to the rear. He had hired the esteemed architectural firm of Severance & Van Alen to design the $500,000 extension. But then, he changed his mind.

On November 12, 1922, The New York Times reported, “The house was vacated last Spring and at first only extensive alterations were proposed.” But now, said the article, the old hotel had been demolished and Pittsburgh architect Frederick I. Merrick had designed the 14-floor replacement that was under construction. The $4 million price tag would equal about $64.5 million in 2022.

But it came to an end in the summer of 1934 after Lydia Baker stepped into the coffee shop and was turned away.

The article said:

The main entrance will be from Sixty-third Street through a corridor twenty-three feet wide, leading to the lobby, which will be two stories high and will be surrounded by a balcony and mezzanine floor, on which will be the dining room, breakfast room and children’s dining room, located along the Broadway front. The ladies’ parlors and writing rooms will face Lincoln Square on Sixty-third Street and there will be a ballroom on the Columbus Avenue side.

The New York Herald reported that there would be 627 guest rooms, and “on the ground floor there are to be fourteen stores.”

For more than a decade, the patrons of the café and dining room in the Hotel Empire were exclusively white. That was a policy decision common among high-end hotels and restaurants of the period. But it came to an end in the summer of 1934 after Lydia Baker stepped into the coffee shop and was turned away. The Hotel Empire had just met a formidable opponent.

On August 1, four days of picketing in front of the hotel began. As the picketing continued, members from the four unions and two other groups joined the protest. Then, on August 5, came “a mass meeting attended by several hundred workers in front of the hotel entrance, held under the auspices of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, National Student League and Cafeteria Workers Industrial Union,” said The Daily Worker.

A committee of four, including Lydia Baker, demanded a meeting with the manager and two assistant managers. On August 6, The Daily Worker announced, “Discrimination against Negroes was smashed yesterday at the Hotel Empire, fashionable hotel in an exclusive white neighborhood, at 63rd Street and Broadway, when for the first time in its history, the hotel was forced to serve Negroes in its coffee shop.” That evening, “when dinner was being served, several delegations from the meeting entered the restaurant to see that everything was all right.”

Living in the Hotel Empire in the 1940’s was composer Aaron Copland. Nearly half a century later, on his 85th birthday, he was honored at Avery Fisher Hall. As he stepped out of his limousine that night, he glanced across the street. According to The New York Times, “’I can’t believe it’s the Hotel Empire,’ he said, reminding his friends that some 40 years ago, when symphonies and songs danced regularly from his mind to his piano, the hotel was his home. In those days, there was a music studio on the lot across from the hotel at Broadway and 63d Street. The spot is now Avery Fisher Hall.”

In May 1950, a syndicate that also operated the Plymouth Hotel on West 49th Street leased the Hotel Empire. The new proprietors brought national attention to the property when the first of the annual United States chess championships was held in the ballroom. None of the matches were more closely followed than those between Bobby Fischer and Samuel Reshevsky in August 1961. The annual battles were held here through the late 1960’s.

The proximity of the Hotel Empire to its across-the-street neighbor, Lincoln Center, affected the hotel’s personality. In 1990 Nolan Studios, which had painted more than 2,000 Broadway and New York City Ballet sets, began a mural in the mezzanine of the Empire Hotel. “It’s going to be romantic, misty, very Swan Lake-ish,” design director Rise Abramson told Newsday journalist Beth Sherman.

And in the summer of 1995, Lincoln Center’s Out-of-Doors series incorporated the hotel as its stage. Chairs were set up in Fountain Plaza and the performance piece C’Est la Vie took place in the hotel. Audience members were given binoculars and wireless headsets, and then partook in choreographed voyeurism. From 45 rooms facing the Plaza, actors and actors created intimate scenarios. “There are stories unfolding among the 11 spotlighted ‘families’ whose interweaving tales, acted out on platforms inside the windows, make up the very loose theme that [Veronique] Guillaud, a doe-eyed Parisian with a cosmic approach to theater, is presenting in this latest of her site-specific productions,” reported Newsday on August 4.

…in the summer of 1995, Lincoln Center’s Out-of-Doors series incorporated the hotel as its stage.

As the hotel prepared for a sweeping renovation in 2004, it met opposition by six resilient permanent residents. The owners, The Chetrit Group, could not proceed with the project without a non-harassment certificate from the city. A somewhat surprising compromise was struck with the help of Councilwoman Gale A. Brewer.

When the three-year renovation was completed in 2007, Chetrit Group had provided the permanent residents what Brewer called “very nice” single-room occupancy accommodations, rent-free for as long as they remained.

In reporting on the Hotel Empire’s reopening on August 16, 2007, The New York Times architectural columnist David W. Dunlap noted that the two-story lobby had been refurbished “with a deliberately ‘50s kitsch sensibility, in a palette of gold and bronze, ocher and chocolate, zebra stripes and leopard spots.” Among the most noticeable changes were the rooftop bar and restaurant. Here, in the winter, according to Newsday on January 20, 2012, there is “a steady fire in the hearth and plush couches where visitors can linger, taking in killer view of Lincoln Center.” The article said the “dimly lit spot is perfect for a little canoodling over cocktails.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Keep the spirit of San Juan Hill alive! Support these local businesses at 1889-1895 Broadway:

Explore Even More!

Read more about this building from our partners at the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project!

Aaron Copland Residence

at the Hotel Empire