Columbus Hill Community Center

224 West 63rd Street – Henrietta Industrial School/Columbus Hill Community Center

by Jessica Larson

San Juan Hill had numerous institutions dedicated to education, health, and childhood. Though most were the results of Black-directed and organized reform efforts, the neighborhood had one prominent white-run institution: the Henrietta Industrial School. This later became the Columbus Hill Community Center, which was primarily staffed by Black workers. Founded in 1892 by the Children’s Aid Society (CAS), the Henrietta Industrial School, which focused on skill-based training, was one of the most well-known reform projects in San Juan Hill.

Sited at 224 West 63rd Street, the Henrietta Industrial School was located in a former home for recently released ex-convicts, likely built circa 1890. When built, the block was still relatively industrial and empty of residential developments. As was typical for the 19th century, there were other charitable institutions located nearby, sited outside of the dense urban downtown; the Roosevelt Hospital (now Mount Sinai West) and New York Infant Asylum were nearby. In 1892, the Children’s Aid Society (CAS) purchased the four-story building at 224 W. 63rd. The CAS, perhaps best known for their controversial Orphan Train Movement, wherein poor children from urban areas were placed with rural foster families (sometimes without the knowledge of their parents), was one of the most prolific children’s welfare organizations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Historically, they had primarily targeted white immigrant communities and excluded Black children from their services. Like many of their other locations throughout Lower Manhattan, the CAS intended for the West 63rd Street location to be an industrial school. Industrial schools were institutions that focused on preparing children and adolescents for work and generally trained them in manual labor. These institutions were not exclusive to Black children, though historical scholarship has most significantly examined their relationship to race. While some, such as Booker T. Washington, celebrated these schools as realistic paths to economic stability, others, like W.E.B. DuBois, criticized them as simply conditioning young Black people for subservient labor that offered little social or economic mobility.

The CAS’s Henrietta Industrial School did not initially cater to a Black clientele. When the school began in the 1890s, the area did not yet have a significant Black population. In response to the area’s unusually high volume of disabled children, the CAS’s founder, Charles Loring Brace, made the decision to have the building adapted to better accommodate children with disabilities in 1898. Several rooms in the building were reserved for the instruction of disabled children and new furniture of varying heights and chairs that were able to recline were purchased for the comfort of differently abled students. To relieve discomfort from their disabilities, there was a dressing room connected to the bathroom facilities that included a table for massage treatments, a sitz-bath, and storage for equipment that pertained to necessary treatments.

Historically, they had primarily targeted white immigrant communities and excluded Black children from their services.

To the left of the building was a large masonry gate with stable-style doors; these would have opened into something called a “horse walk,” a passageway that allowed a carriage to be brought from the street to the rear yard. Upon the expansion of the school’s services to include the teaching and care of disabled children, the CAS purchased a wagonette to transport them to and from the school; this horse-drawn vehicle was equipped with a glass cover to protect against winter weather and would pick children up in the morning then drop them off at home in the evening. This also brought the schools’ women reformers into the homes of these children as they needed to carry them up and down the tenement stairs; this glimpse into the children’s homes helped shape reformers’ perceptions of how the physical environment of poverty shaped the behavior of children. It could also potentially give cause for reformers to petition the city to have children removed from the care of their parents.

By the first few years of the 20th century the student body was almost entirely composed of Black students as the neighborhood became predominantly Black. A central entrance can be seen on photographs of the exterior, which would have welcomed visitors into an area for reception, where children would have been processed and other administrative work done; this area, though, would have primarily been for adults. As with other CAS institutions in Manhattan, the children would have likely been filtered through a side entrance, keeping them out of sight from the administrative functions of the school; girls and boys would have probably had separate doorways. Upon entering the building, the children were likely first led down to the basement level where they would find washing and toilet facilities. After coming in from the dirty streets of San Juan Hill, the children were required to wash up before navigating other areas of the building. It would have been standard for the basement to also have a space for laundry, cooking, and a dining area; in East Coast institutions, children’s dining generally took place in the basement. However, other CAS buildings in New York City located their dining facilities on the ground floor, so it is possible that the Henrietta followed the same format.

The curriculum of industrial schools was deeply gendered –girls learned skills that would prepare them for domestic service while boys learned manual trades. These classes were probably held in the upper stories of the building. Girls learned the basic skills that they would later use to either care for their family or, particularly in the case of Black girls and women who primarily worked in domestic employment, serve middle-class white families. What white reformers for places like the Henrietta hoped was that their instruction would condition young girls early for work in serving trades. For this purpose, too the Henrietta included a model flat – an aspirational mock of an apartment where girls would practice cleaning and tidying prototypical middle-class furniture. This was possibly located in one of the upper stories. Similarly, boys learned skills that prepared them for future trades, such as cobblering and carpentry. Photographs show young boys learning riflery and practicing playing musical instruments in a marching band.

Despite the fact that the building was owned and managed by white reformers, Black residents of San Juan Hill were able to exert some influence over the use of the institution. As West Indian immigration surged in the first decade of the 20th century, the religious demographics of the neighborhood shifted; one growing denomination was the Moravian Church. In 1901, a group of 28 West Indian Moravians secured use of a room in the Henrietta Industrial School to be used as the Third Moravian Church; there, they organized religious classes but also dedicated themselves to reform efforts in the neighborhood. The church was central to the founding of the West End Workers Association, which met in Union Baptist Church’s building at 202 West 63rd Street, and was central to the improvement of housing conditions in San Juan Hill.

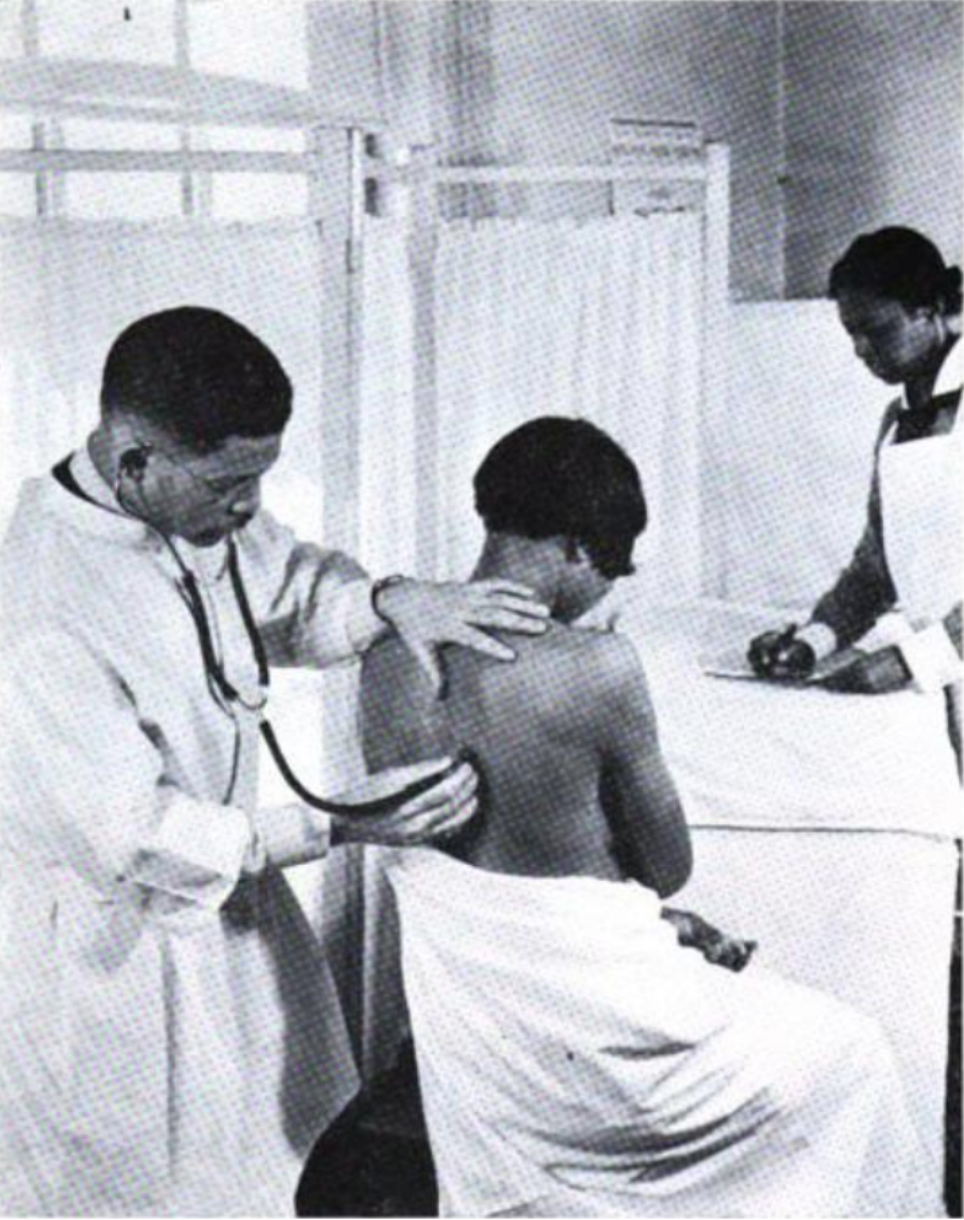

By the late 1920s, the concept of industrial schools had fallen out of favor and, to many, appeared regressive. Via a $72,000 donation from John D. Rockefeller, the Children’s Aid Society renamed and repurposed the Henrietta Industrial School’s building to serve as a center for a variety of types of reform. The newly adapted building –renamed the Columbus Hill Community Center in 1933–included a health center (run by the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor), a station devoted to the health of babies, a nursery, and other agencies related to child development and education. The center was quickly a success; within its first months of existence, roughly 150 girls and 320 boys were enrolled as participants in classes and activities, including sports, dancing, music classes, and more. As well the building included a “Boy’s Club” with more recreational activities, such as a pool table. Thelonious Monk, who grew up across the street in Phipps Houses Number 2, later recounted policing younger children during pool games at the Columbus Hill Community Center, where his mother worked as a cook. As it would have been while still the Henrietta Industrial School, children were divided by age group and gender. In spite of the center’s popularity, the CAS announced in April 1930 that they would be closing the institution due to lack of funding. After vocal outcry from residents of the neighborhood, who argued that the CAS was motivated by racism and not financial concern, the Columbus Hill Community Center remained open. In 1934 the center added a playground so as to keep children from playing in the streets.

…the Henrietta included a model flat – an aspirational mock of an apartment where girls would practice cleaning and tidying prototypical middle-class furniture.

The Columbus Hill Community Center closed in 1938 as San Juan Hill’s Black population had mostly migrated to Harlem. The building was demolished as part of clearance to make way for NYCHA’s Amsterdam Houses in 1948.

Resources:

“Anniversary Marked by Moravian Church.” New York Times. October 23, 1933: p. 12.

Charles Loring Brace. “Day Schools for Crippled Children.” The Charities Review, Vol. 10, No. 2. April 1900: p. 79-83.

https://archive.org/details/sim_charities-review_1900-04_10_2

Hart, Tanya. Health in the City: Race, Poverty, and the Negotiation of Women’s Health in New York City, 1915–1930. NYU Press. 2015.

Kelley, Robin D.G. Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original. Free Press. 2009.

Mabel Keaton Stauperes, R.N. “The Negro Nurse in America.” Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life. Vol. 15, No. 11. November 1937: p. 339-345

Newton M. Shaffer, M.D. “On the Care of Crippled and Deformed Children.” New York Medical Journal, Vol. 68, No. 2. July 9, 1898: 37-40.

The New York Age (New York, NY)

June 30, 1928

July 21, 1934

June 12, 1948

“Something About one of New York’s Noblest Charities.” The Old Ladies Journal (Leavenworth, Kansas). February 1, 1901: p. 6.

Stocker, Harry Emilius. A history of the Moravian Church in New York City. New York, 1922.

https://archive.org/details/historyofmoravia00stoc/mode/2up

Jessica Larson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is also the Joe and Wanda Corn Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum & National Museum of American History