Dante Alighieri

by Tom Miller

In 1911 the annually-updated encyclopedia Americana noted that “The Sicilian sculptor, Ettore Ximenes” was working on a New York City monument. “It represents Dante, the great Italian poet, and its cost has been met by private subscription among the Italian colony in New York.”

The report sounded benign enough. But a decade-long furor was about to be unleashed.

The project had been initiated by Carlo Barsotti, editor of the Italian-language newspaper Progresso Italo-Americano (better known as Il Progresso). Barsotti was seemingly indefatigable when it came to erecting New York City monuments to his countrymen. He was behind the critically maligned statue of Giuseppe Garibaldi in Washington Square, erected in 1888; the Christopher Columbus monument in Columbus Circle four years later; the 1906 monument to composer Giuseppe Verdi in Verdi Square; and the Giovanni da Verrazano, dedicated in 1909.

The Verrazano monument had barely been unveiled before Barsotti was at work again. On September 25, 1910, The Sun reported “the Italians of New York, who already have given to the city four monuments to their famous countrymen, are contemplating the erection of a monument to Dante Alighieri.” The article said that $8,000 of the estimated $20,000 cost had been received.

The proposed monument would stand 50 feet high and include complex marble groupings. Americana explained that it “will consist of an obelisk surmounted by the national star of Italy, and adorned with the Roman eagle in bronze. A life-size statue of Dante stands on the pedestal under the obelisk, supported by two female figures representing Language and Culture, which stand on opposite sides of the coat-of-arms of the City of Florence.”

Three intricate groupings representing scenes from Dante’s Divine Comedy–Inferno, Purgatory, and Paradise–would adorn the sides and back. Americana projected, “This elaborate work will probably be unveiled in New York City sometime during the summer of 1911.”

That was not going to happen.

For one thing, Barsotti had forged ahead with the project, assuming he would have the blessings of the Mayor, the Parks Commissioners, and the Municipal Art Commission. He had also assumed that members of the Italian community, many of them with little cash to spare, would happily continue to fund his unceasing monument building. Both of his assumptions would cause significant problems.

On July 30, 1911, The Sun reported: “At least part of the Italian community in New York is opposed to giving any more monuments to the city until the community has raised money for a hospital or two or a school or other kind of institution that will uplift some of the crowds of Italians that they are sure need helping in the worst kind of way here now.”

When newspapers in Rome took up the cause against the memorial, Carlo Barsotti counter-attacked.

Additionally, the four other Italian-language newspapers accused Barsotti of seeking “personal glory.” An editorial in the Italian Journal said in part, “We do not need more monuments. We are constantly hearing in America of the number of criminals in the Italian community. We constantly see the number of poor among us. We need to avoid this charge of becoming a burden upon the State and we can’t do it by monuments, but by schools and hospitals.”

Frank l. Frugone, the editor of the Bolletinno Della Sera, said, “This monument craze was entirely the wrong lead for the Italians in New York…and it is time that it should be stopped.” He sent a letter to Mayor William J. Gaynor insisting that the majority of New York Italians were opposed to the Dante memorial and that “there is too much personal and newspaper aggrandizement in the scheme.”

When newspapers in Rome took up the cause against the memorial, Carlo Barsotti counter-attacked. On January 21, 1912, the Virginia newspaper the Times Dispatch reported he had sued “several Roman newspapers for alleged libelous statements in connection with the erection of the Dante statue.”

Despite the turmoil, Barsotti ordered the massive monument shipped, fully aware that the City had not provided a site for it. A special cable from Naples on May 11, 1912, to The Sun read: “The Dante monument which is to be erected in one of the New York city parks was shipped to New York to-day on the steamer Moltke.” The newspaper added, however, that the memorial “has been the cause of much dissatisfaction among a large part of the Italian population in New York” and that “Commissioner Stover has refused to grant a site for the Dante monument until he sees the statue.”

The Dante Memorial arrived in Hoboken with no place to go. On June 1, 1912, the New-York Tribune ran the headline “Dante In Inferno Here / Poet’s Statue Ingloriously Scattered About Piers.” Parks Commissioner Charles B. Stover refused to grant a site, saying, “I have not been convinced that the Italians as a whole want this monument. In fact, the Italian government will not participate in its erection in any way, and when you come to think that Dante was the greatest Italian of all items, and the government does not care to take part in the unveiling of a monument to him, it is best to consider the reasons why.”

Things only got worse when, on July 3, 1912, the Municipal Art Commission announced that the monument “had been rejected because of its architectural defects.” It was not Ximenes’s bronze figure that offended the committee (which included esteemed artist Robert W. De Forest and sculptors John Quincy Adams Ward and Carl Bitter), but his overblown marble base. The Sun reported, “No reflection was made upon the Dante statue, but it was said that the assembling of the statue, pedestal, shaft and the architectural work generally was not acceptable.”

Undaunted, the monument’s supporters tossed ideas around for highly visible sites. The New-York Tribune included, among them, “Bryant Park, the Mall in Central Park, the 59th street and Fifth avenue plaza and Long Acre Square [later renamed Times Square].”

Four months later, the 232 crates still gathered dust and storage fees in New Jersey. Sculptor Ettore Ximenes arrived in New York to fix things. The New-York Tribune reported on September 22, 1912, “The sculptor has brought with him from Europe a plaster model of the monument, and this, he declared, would give the commission a far better idea than did the photographs.”

Ximenes declared the split among New York Italians over the monument “deplorable” and said that not only the Italians, “but all persons, should be as one in the rearing of a monument to Dante.”

Despite the sculptor’s optimism that he could clear up the conflict, the project remained stalled. The Municipal Arts Commission insisted that he simplify the base. (The Sun ran a sub-headline saying, “Figure Declared Unfit for Polite Park Society Unless Revised.”) Ximenes did not agree.

The Sun seemed to delight in reporting on April 6, 1913, “Dante in marble has been reposing on a pier of the Hamburg-American Line in the barbaric town of Hoboken, judged from the standard of the sculptor of the unhappy Italian poet, for one fretful year.” The article reported that the Hamburg Pier had lost patience and insisted that the crates on its several piers be moved.

They were brought to Manhattan and put in storage “in the Ninety-seventh street yards in Central Park,” according to The Washington Times, which added, “Things are, indeed, breaking badly for Dante. And from all indications, there is no telling when they will do otherwise.”

Although Ximenes finally conceded to rework his plans as demanded by the Municipal Art Commission, Former Parks Commissioner Stover was still adamant that the monument would never be erected. The Washington Times wrote, “‘Let the plans come,’ he said. ‘There are fully 10,000 Italians who do not want that monument erected in New York. We are waiting for Mr. Barsotti to try to erect it. Then we will go to Mayor Mitchel, to the Art Commission and park commissioner to have it stopped.”

And, sure enough, the monument was stopped. The crates sat forgotten by almost everyone but Carlo Barsotti and Ettore Ximenes. Then, on February 20, 1921, nearly a decade after the monument arrived in America, The New York Herald reported that in a meeting in Rome, that city’s mayor, Luigi Rava, and Ettore Ximenes had “urged the raising of a Dante monument in New York” and said, “It was suggested that the present year would be suitable for the occasion as it is the six hundredth anniversary of Dante’s death.”

Then in the spring of the following year, vandals attacked.

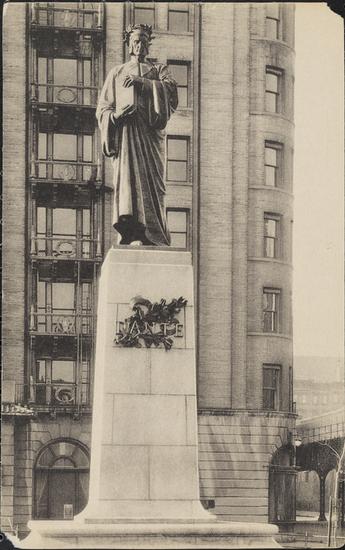

The City, seemingly begrudgingly, agreed. But the over-zealous marble base was still deemed unacceptable. The architectural firm of Warren & Wetmore was commissioned to design a simple stone pedestal. The sole survivor from Ximenes’s base design would be a single bronze garland announcing the poet’s name.

The unveiling took place on November 5, 1921, in the little triangle called Empire Park at 63rd Street and Broadway. It was an anti-climatic victory, largely ignored by newspapers. There were no prominent articles on the ceremonies.

Two weeks later, on November 29, The Committee on Public Thoroughfares resolved to change the name of the site to Dante Park.

Incidentally, Carlo Barsotti got revenge of sorts when he personally presented a second, identical casting of the statue to Washington, DC, on December 1 (it, too, had a simple stone base). That ceremony was attended by President and Mrs. Harding.

Ettore Ximenes’s marble sculptures remained crated and forgotten in the Central Park storeyard until, as described by The New York Times, they were “rescued from twenty years of oblivion.” The statues of angels and mortals were discovered by W. Earle Andrews, general superintendent of the Parks Department, in 1934 “under a pile of scrap iron in the Ninety-seventh Street storeyard.”

The statuary was resurrected and lined up in Central Park, awaiting placement in various parks and playgrounds. Then in the spring of the following year, vandals attacked. On March 21, 1935, The New York Times reported “Nine figures had been beheaded, and their heads lay yesterday in a neat row which also included parts of arms, broken wings, and anything, in fact, that had protruded sufficiently to be broken off.”

While the president of the Art Commission, I. N. Phelps Stokes, lamented the vandalism, saying the sculpture was “a good piece of work by a capable artist;” Karl Gruppe, chief sculptor of the WPA’s Monument Restoration Project, added to the insults of 1912. The New York Times reported “He said it was of ‘poor design’ and should have been condemned and destroyed anyway. In his opinion, the work of the vandals merely had saved the Park Department some trouble and perhaps controversy.”

The disgrace and controversy of Ettore Ximenes’s noble (if somewhat sinister appearing) bronze figure of Dante faded. In 1992 it was conserved and restored by the Radisson Empire Hotel, and again refurbished by the City Parks Foundation Monuments Conservation Program in 2001.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Keep the spirit of San Juan Hill alive! Learn more about this Monument in our Public Art Survey: