Church of the Good Shepherd

by Tom Miller

In 1887 development of the Upper West Side was picking up speed after the Panic of 1873 had brought construction nearly to a standstill. Now, lured by improved transportation, new sewer lines, and street paving, developers rapidly filled blocks with rows of upscale and middle-class homes.

But not all of the Upper West Side was so comfortable. The neighborhood that somehow acquired the nickname San Juan Hill stretched roughly from 59th Street to 65th, and from Amsterdam Avenue to 11th Avenue. While New York’s other grittiest neighborhoods–Hell’s Kitchen immediately to the south, Mulberry Bend and Five Points—were made up of a mix of ethnicities, San Juan Hill’s residents were almost exclusively black. It was a district of gang violence, bloodshed, poverty and hopelessness.

With development came the need for stores, schools and churches. The West Presbyterian Church on 42nd Street took a page from its Episcopalian and Roman Catholic counterparts and laid plans for a mission church.

On January 6, 1884 a meeting was held in the church, led by its well-known pastor the Rev. Dr. John R. Paxton. Frank Leslie’s Sunday Magazine described it as “a meeting in the interest of church extension in this city.” The magazine noted that “The need of new churches on the east and west sides…was spoken of in detail.”

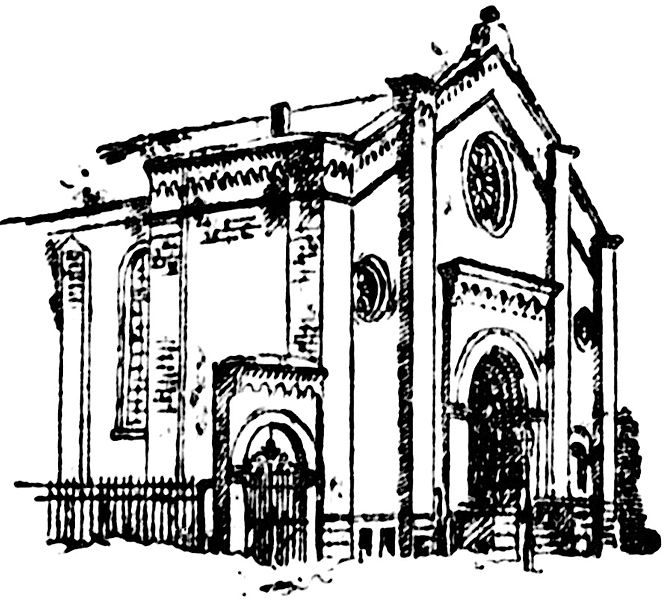

For the West Side the church chose the plot of land at No. 152 West 66th Street; on the eastern fringe of San Juan Hill. And for its architect it selected J. C. Cady & Company. Josiah Cleaveland Cady, who was known professionally as J. Cleaveland Cady, designed a wide variety of structures—from hotels and libraries to churches and synagogues. In 1887 he put pencil to paper for the design of what would become the Church of the Good Shepherd.

It would be another six years before the church became a reality. On February 4, 1893 The Evening World reported “The new Church of the Good Shepherd, on Sixty-sixth street, west of the Boulevard, will be dedicated at 11 o’clock to-morrow morning.” It added “The church is a branch of Dr. Paxton’s West Presbyterian Church on Forty-second street.”

“Mrs. Hannah’s report of the work in the Church of the Good Shepherd, a mission of the West Presbyterian Church was very gratifying.” But, it admitted, in a not-so-Christian response to African American worshipers, many congregants had left.

Costing $90,000 (in the neighborhood of $2.5 million today), it was capable of seating 750 worshipers. Cady had produced a charming Italian Romanesque structure of light-colored brick. The New-York Tribune called it “characteristic of many old Italian churches.” Indeed, it shared many elements of country churches of the Southern Sicilian Romanesque style.

Within its first years the mission church seems to have done what it was intended to do—serve the underprivileged residents of San Juan Hill. But that success came with a cost. On May 16, 1900 the annual meeting of the congregation of the West Presbyterian Church was held. Reports were read concerning the activities of the church’s various organizations.

The New-York Tribune reported on the following morning that “Mrs. Hannah’s report of the work in the Church of the Good Shepherd, a mission of the West Presbyterian Church was very gratifying.” But, it admitted, in a not-so-Christian response to African American worshipers, many congregants had left. “In reading a report of the pastor of the Church of the Good Shepherd, Dr. Evans said that the flood of colored population in the neighborhood of the church caused a falling off, and that 129 names had been stricken from the rolls. Still, the church was prosperous.”

In 1926 pastor Rev. Dr. F. R. Clee was called upon to lead an unusual funeral service. William Henry Johnson had died of pneumonia at the age of 84 in Bellevue Hospital. His funeral was held at the Campbell’s Funeral Church nearby at 66th Street and Broadway, on April 28.

Better known as “Zip—What Is It?,” he was called by The New York Times “the famous freak, one of the first to be exhibited by P. T. Barnum back in the ‘60s.” The newspaper’s account of the funeral was less reverential than sarcastic.

“Circus sideshow folk, giants, fat girls, sword swallowers, tattooed men and rubber-neck men filled the chapel, and their faces showed their sorrow.” The article listed performers who had come from as far away as Chicago. “Then there was Alfonso, the human ostrich, who ate glass and other things for thirty-five years alongside of Zip at the sideshows of the circus and at Coney Island…Other circus freaks who attended were Lillian Maloney, the Albino girl; Carrie Holt, fat girl; Gus Birchman, the iron claw man; Frank Graef, tattooed man; Ajax, sword swallower; Joe Kramer, the rubber neck man, and Maharajah, the ‘This way, laydees and gentl-el-men’ lecturer of the Seaside circus sideshow of Coney Island, where Zip spent his Summers.”

Johnson’s funeral was, despite the description, conducted with dignity. Organist and tenor Alexander Blander sang “Lead Kindly Light” and “Going Home,” from Anton Dvorak’s New World Symphony.

On November 13, 1932 the 45th anniversary of the Church of the Good Shepherd was celebrated. In his sermon that morning, the Rev. William F. Wefer questioned whether things had really changed much in nearly half a century.

“A striking sameness may be noticed in the years 1887 and 1932. About forty-five years ago we had sweeping Democratic victories just as we had this past week. Charges of political corruption were hurled about then.

“The problems of that day were much the same as our own. Fashions may change, but there is still the clamor over women’s dress. Today we have gangsters, then we had gangs. Today we have speakeasies, then we had ‘blind pigs.’ The ‘by-cycle-scorchers’ have given way to the reckless automobile drivers.”

Certainly one thing that had not changed was San Juan Hill. The 1940 census indicated that the neighborhood was still exclusively black. Residents still struggled and families were confronted with the problems of violence, gangs and crime.

Twelve-year old Martha Punt was one of the local girls who tried to better herself. She regularly attended Sunday School at the Church of the Good Shepherd. Martha lived with her mother, Elizabeth James, who was separated from her second husband. The girl tried her best to survive in the squalid neighborhood. In December 1943 a 63-year old street cleaner was accused of “trying to impair the child’s morals,” according to The New York Times. The charge was dismissed on December 19.

Martha Punt would never make it to her teen years.

A month later, on the morning of January 20, 1943, her brutally battered body was found in the “poorly furnished” fourth floor apartment of two kitchen workers, at No. 513 West 59th Street. She had been beaten about the head with a claw hammer and her throat cut.

The tragedy brought together at least some of the locals. Three days later The New York Times reported “Martha Punt will not be buried in potter’s field, for the people of San Juan Hill yesterday were able to raise $138 to give the slain 12-year old schoolgirl a fitting funeral service and burial.

On May 9, 1957, 400 people attended a rally at the church to protest the redevelopment project. While the envisioned Lincoln Center would replace urban blight; it would also put more than 40,000 residents on the street.

“Even strangers strolled into Abe Sable’s bar and grill at 2 Amsterdam Avenue to deposit dollar bills and coins in a beer container to help the family of the girl, who was brutally beaten to death in an apartment at 513 West Fifty-ninth Street Wednesday morning.”

The pastor of Good Shepherd, the Rev. Charles E. Souter, officiated at Martha’s funeral.

By now the name of the church had become Good Shepherd-Faith Presbyterian Church. When Faith Chapel, another of West Presbyterian Church’s missions, gave up its building at No. 423 West 46th Street, the two congregations merged.

Around 1953 the Comic Opera Guild began giving presentations at Good Shepherd. It was the beginning of a tradition of musical concerts and plays here. But both concerts and religious services nearly came to an end when Robert Moses laid plans for his ambitious Lincoln Center project.

Moses had been approached by Fordham University and the New York Philharmonic which were seeking venues in Mid-Manhattan. His solution was to eradicate a slum and replace it with a fine arts complex. He faced opposition by some groups—including the Lincoln Square Chamber of Commerce and the Good Shepherd-Faith Presbyterian Church.

On May 9, 1957, 400 people attended a rally at the church to protest the redevelopment project. While the envisioned Lincoln Center would replace urban blight; it would also put more than 40,000 residents on the street.

The local groups were defeated and the city began demolition of 16.3 acres of buildings—all except the Good Shepherd-Faith Presbyterian Church. The stubborn little building managed to hold out as everything around it was bulldozed to rubble.

The church continues its role as a performance center—in the 1990s productions by the Seventh Sign Theater Company were staged here. Ever changing with the neighborhood, it became home as well to the Korean Central Church and the Catholic Apostolic Parroquia del Espirit Santo y de Nuestra Senora de la Caridad. The three Sunday services are performed–one each in English, Korean and Spanish.

The last vestige of San Juan Hill in the immediate Lincoln Center area, J. Cleaveland Cady’s remarkable Italian Romanesque mission church is a miraculous and stunning survivor.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com