The 68th Street Station House

by Tom Miller

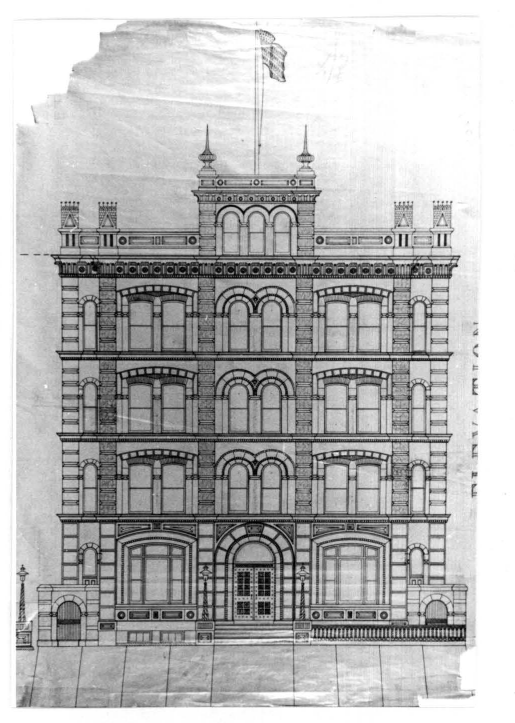

By the late 1880’s the burgeoning Upper West Side district demanded a police station. The city acquired the building plots at 150 and 152 West 68th Street in 1890 as the site for a new “station-house, lodging-house and prison,” as reported by the Real Estate Record & Guide. Police Sergeant Nathaniel Bush, who was responsible for designing the force’s new station houses from 1862 to 1895, laid out the plans and specifications. He saved himself time by recycling his plans for the East 67th Street Station House, erected three years earlier. (As a matter of fact, Bush would re-use the same plans at least one more time.)

Construction was completed in 1892. The four-story brick structure, trimmed in bluestone and terra cotta, was a medley of styles–Second Empire, Romanesque Revival (specifically the German Rudbogenstil substyle), Neo-Grec and Renaissance Revival. The first floor held the sergeants’ desk and waiting room, and the captain’s room. On the second and third floors were dormitories for the officers and sleeping rooms for four sergeants. Behind the main building was the two-story jail with 20 steel cells, separated by an open court, or yard.

Three years after its opening, the West 68th Street Station House was chosen for what some considered a startling innovation in police work—the bicycle policeman. On December 13, 1895, The New York Times reported, “The first of the municipal police to do patrol service on bicycles started out last night at 6 o’clock.” There were just two policemen assigned to the new duty—Dennis Gleason and Henry Negglesmith. The article said, “The men started out on duty when the night platoon left the West Sixty-eighth Street Station.” Their purpose, explained Captain Chapman, was “to pay especial attention to vehicles and bicycle riders on their beats. Their duty was to stop too great a speed in driving or wheeling [i.e, bicycling].”

Tensions between the all-white officers and San Juan Hill’s residents were severe. The 68th Street Police Station’s “strong arm squad” covered the area, often using extreme force—what today would be termed police brutality.

The news that there would be cops on bicycles spread throughout the neighborhood, and by 6:00 “there was a big crowd of men and boys standing in the street waiting for the door to swing open and the bicycle brigade to come forth.” Any disappointment they may have had in the lack of numbers was nullified by Gleason’s and Negglesmith’s appearance. The article noted, “the men who started are expert riders, nevertheless they looked odd with their long uniform coats, and some in the crowd did not hesitate to say so.”

The officers of the 24th Precinct (it would be renumbered the 26th Precinct in 1901, the 28th Precinct in 1907, and the 20th Precinct by 1943) had more serious issues to deal with than speeding bicyclists, however. Included in the precinct boundaries was the San Juan Hill neighborhood, which stretched roughly from 59th Street to 65th, and from Amsterdam Avenue to West End Avenue. While New York’s three other grittiest neighborhoods–Hell’s Kitchen immediately to the south, Mulberry Bend and Five Points—were made up of a mix of ethnicities, San Juan Hill’s residents were almost exclusively black. It was a district of gang violence, bloodshed, poverty, and hopelessness.

Tensions between the all-white officers and San Juan Hill’s residents were severe. The 68th Street Police Station’s “strong arm squad” covered the area, often using extreme force—what today would be termed police brutality. That, in return, fostered hatred and attacks from the San Juan Hill’s inhabitants. Typical was an incident in July 1903 when officers attempted to clear the street in front of a saloon on West 62nd Street. Someone hurled a brick at them from a rooftop.

Police swarmed into the saloon, clubbing the black patrons, and shooting their pistols. Other officers raided a billiard room across the street and arrested all the patrons on suspicion. A black carpenter who was climbing over a fence to escape the melee was shot and seriously injured. Another man, Arthur Moody, was suspected of having thrown the brick. He was beaten and shot, and later died at Bellevue Hospital. (Witnesses later said he was innocent of the brick-throwing.)

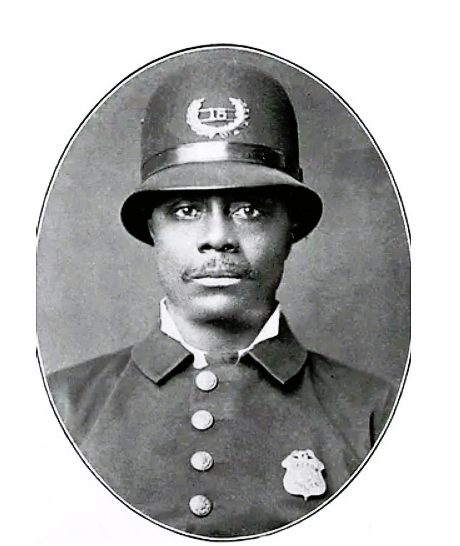

The New York City Police Department faced a conundrum in 1911. Samuel Jesse Battle first passed the Civil Service test with a score of “more than 84,” and then graduated from school of instruction—what today we know as the Police Academy. The problem was that Battle was black, and the Police Department was entirely white. And so, Commissioner Cropsey rejected him “on physical grounds.” That resulted in pressure on the mayor from black constituents, and Battle was given a second physical, which he passed. The Department was forced to swear him in. Now the only black officer in the New York City Police Department was assigned to the 68th Street Station House. And it did not go well.

On June 29, 1911, The Sun reported that among the 40 new probationary officers “was a big, husky negro who topped his comrades by several inches…The negro is Samuel J. Battle, and he lives at 27 West 116th street. He weighs 235 pounds, is six feet tall, and has a tremendous chest and arms.” Two months later the newspaper followed up on the story.

The policemen attached to the West Sixty-eighth street station house, to which Samuel J. Battle, the only negro patrolman on the force in Manhattan, was assigned, have resented his presence there and have taken steps to impress their state of mind on their new colleague. This has taken the form of as severe a silence as was ever imposed on any unpopular member of the West Point faculty.

The article said that none of the policemen would address him nor answer a question. The one time he was spoken to, it said, was when Battle asked an officer a question regarding the hours of duty.

“Don’t ask me for any direction you —– black ——. Go ask the captain,” was the response.

He eventually won their respect by never complaining nor discussing his ill treatment to the press. He was repeatedly promoted, finally to lieutenant in 1935, and upon his retirement in 1941 was appointed the city’s first black parole commissioner.

The article surmised that the difficulties with the San Juan Hill residents contributed to Battle’s unpopularity. “The turbulence of the neighborhood, which usually reaches its height in the dog days, had additional incentive in a recent visit of the so-called strong arm police squad to that neighborhood,” it said. “The result of this raid was to increase the hatred of the San Juan dwellers for the police. There have been several violent conflicts recently.”

Oddly enough, said the journalist, “Battle has not yet been sent to the negro quarters and has rather pointedly been kept in other parts of the precinct. It was supposed when he was first assigned to West Sixty-eighth street, that he would be detailed to keep order among his own people.”

As it turned out, Battle was more resilient than his detractors were persistent. He eventually won their respect by never complaining nor discussing his ill treatment to the press. He was repeatedly promoted, finally to lieutenant in 1935, and upon his retirement in 1941 was appointed the city’s first black parole commissioner.

The passage of time did not improve relations between the West 68th Street Station House officers and the San Juan Hill residents. On October 4, 1920, for instance, the New-York Tribune reported, “While on his way home to 128 West Sixty-third Street shortly after 3 o’clock, Policeman John F. Rein, attached to the 28th Precinct, was set upon by four men who knocked him down and kicked him in the head. He managed to draw his revolver and shoot two of them.” Both wounded attackers later died at Bellevue Hospital.

The men of the West 68th Street Station House continued to carry out their duties throughout the rest of the century, dealing with white collar crimes, speak-easies, gangsters, murderers, embezzlements, and all other manner of law enforcement issues. On May 7, 1931, for instance, police engaged in a gun battle with fugitive murderer Francis “Two Gun” Crowley. The New York Times reported, “Crowley fired desperately for two hours at 150 policemen massed outside of a rooming house on West End Avenue where he had taken refuge.”

But it came to an end at noon on March 29, 1972, when the doors were closed and locked for the first time in eight decades. The officers moved into the new 20th Precinct Station House at 120 West 82nd Street.

The New York Times remarked on the stark differences in the two buildings—the newer one having air conditioning, an auditorium, and comfortable dormitory beds. “But to many a police buff,” said the article, “the old station—with its walls of police-station green, its 22-foot-high ceilings and its magnificent Victorian fireplace with a secret compartment—was reminiscent of the days of celebrated gangsters and blood-tingling shootouts.”

Nathaniel Bush’s handsome Victorian station house was replaced by a modern apartment building.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com