26 West 61st Street

by Jessica Larson

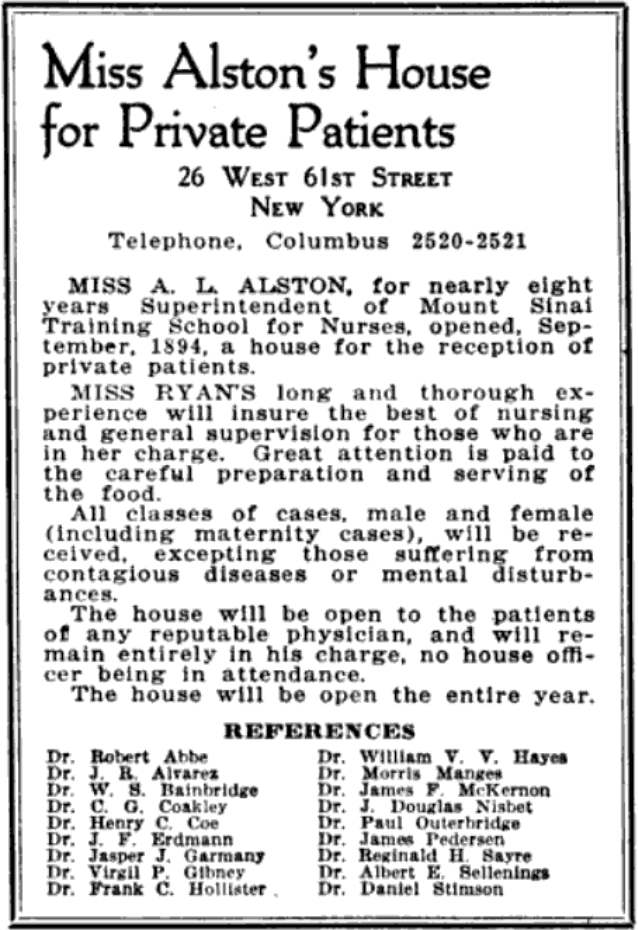

In April 1903, Miss Alston’s House for Private Patients (also referred to as Miss Alston’s Sanitarium) opened at 26 West 61st Street. Formerly at 143 West 47th Street, the institution relocated to the West Side’s expanded facilities with improved amenities, such as private bathrooms.

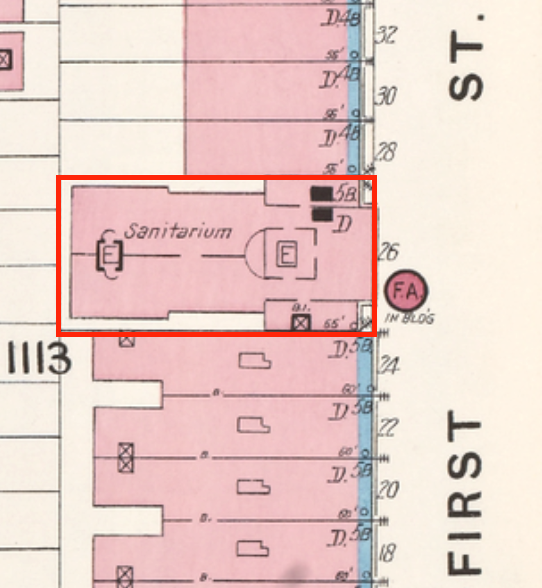

The building was constructed in 1884 by architects Schwarzmann & Buchman. Based on later photographs of the exterior and the “footprint” (or, outline) of the building, it probably served as an apartment building, albeit nicer than your standard tenement. The building was five stories, spanned two lots, and was in a large “T” shape. Seven families are listed as residing in the building on the 1900 Federal Census. All of these families were white, presumably middle class. The most surprising former resident, not listed on the census but who listed her address as 26 West 61st Street in publications and private correspondence, was suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The earliest available letter that mentions this address is from 1891. She later moved to 230 West Ninety-fourth Street where she died in 1902; though that building was demolished, the apartment building that replaced it was named “The Stanton” in her honor.

Miss Alston’s House for Private Patients took over the building in 1903. The institution’s namesake, Anna L. Alston, was an experienced nurse who had previously served for eight years as the Superintendent of Mount Sinai Training School for Nurses. Alston was born in 1853 in New Jersey and is listed on the 1910 Federal Census as residing in the West 61st Street location, which would have been typical. Numerous other nurses, all white, were also listed as living at the address. The institution allowed for both male and female patients, including pregnant women. The institution did not, however, allow patients with contagious diseases or “mental disturbances.” As would have been standard, the ground floor likely had a room for reception where patients were greeted and processed. Men and women certainly would have had segregated quarters, either by floor or on different sides of the building. The top floor was probably reserved for operations, which was usually the case as those stories offered the most natural lighting. The rear of the lot included a courtyard.

The most surprising former resident…was suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Prior to the widespread creation of hospitals as we think of them today –large, purpose-built structures specially designed with health and medicine in mind –these sorts of smaller institutions were widespread. They often occupied former residences, which were fairly easy to adapt to patient needs; further, these structures offered the comfort of the patient still feeling like they had the privacy of their home. These institutions were available, at a price, to the middle and upper classes, but the poor generally had to seek other options. Many relied on charitable clinics or “visiting nurses” who would go to the homes of the poor. For poor pregnant women, particularly immigrants, midwives who would come to their home and help during delivery and postpartum care were commonplace. Certainly, hospitals existed and were used, but they were often avoided by the rich and poor alike for numerous reasons.

The institution seemingly ceased operations sometime in the late 1920s; the last available mention comes from 1925. The building was then transitioned into the Saxonia Hotel. The 1930 Federal Census lists 42 guests at the hotel (all white, although one was Jewish), with 11 of them being immigrants. By the 1930s, the area had become a home to many white European immigrants, particularly from Northern and Eastern Europe. By the 1940s, this was still mostly true, but by the 1950s the occupants of the hotel had become a bit more diverse. Guests listed as hailing from India, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico are listed on the census. The site was redeveloped in 1982 as the mixed-use Beaumont Condominiums.

Resources:

1900 United States Federal Census, New York, Borough of Manhattan Enumeration District 419, Election District 21, Ward 17, image 20/25. Familysearch.com.

1910 United States Federal Census, New York, Borough of Manhattan, Election District 1319, Ward 22, image 12/30. Familysearch.com.

1930 United States Federal Census, New York, Borough of Manhattan (Districts 0251-0500), Enumeration District 379, image 45/55. Familysearch.com.

“Fire in Private Hospital.” The Sun. January 26, 1906: p. 3.

“Many Women Rescued At A Sanitarium Fire.” The Brooklyn Citizen. January 25, 1906: p. 6.

“Miss Alston’s House for Private Patients.” The Cornellian Vol. 34. Cornell University, Ithaca, New York. 1902.

“Miss Alson’s House for Private Patients.” The New York Medical Week Vol. 1, no. 3. New York Medical Week, Inc., New York. 1922.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. “The Woman’s Bible.” The Critic Vol. 28. The Critic Company, New York. 1896.

Stanton, Theodore, and Harriet Stanton Blatch, eds. Elizabeth Cady Stanton as Revealed in Her Letters and Diary and Reminiscences, Vol 1. Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York. 1922.

“T.A. McIntyre Found.” New York Times. May 6, 1908: p. 9.

Jessica Larson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is also the Joe and Wanda Corn Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum & National Museum of American History