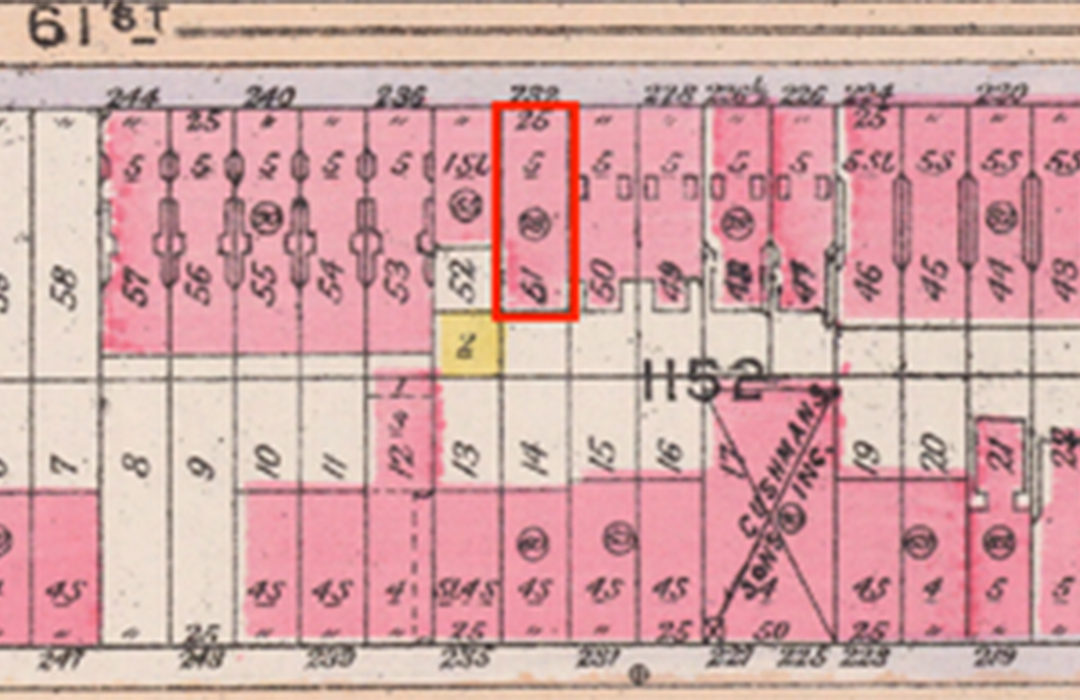

1916 Bromley Map with No. 232 West 61st Street marked in red. Image by New York Public Library.

231 West 61st Street

by Jessica Larson

At 232 West 61st Street stood a five-story brick structure, a nineteenth-century building that lasted well into twentieth-century San Juan Hill. Like other residential and commercial buildings throughout the neighborhood, the life of 232 West 61st Street reflected the changing times in the neighborhood.

It is unclear exactly when the building was constructed, but it had to have been prior to 1891 but after 1879. Given the building’s “footprint” (or outline) as visible on fire insurance maps, it was intended as a single-family residence. At some point, the building was likely renovated or subdivided to accommodate multiple units. According to the 1900 Federal Census, seven families lived in the building, and several of those families lodged boarders. All of these tenants were white; most families either immigrated from Ireland or were the children of Irish immigrants; one tenant was from Scotland, and one family immigrated from Austria. By 1910, this had radically changed. The building was almost entirely comprised of Black tenants; six families are listed, some with boarders, with most coming from the South, the West Indies, or New York. Curiously, and very oddly for the time, there was one white male lodger listed as living in the building. This man, named J.R. Bronkhurst, was a 50-year-old widower who had immigrated from England. He lived in a unit rented by a young Black married couple from the South, along with four Black lodgers. While it was far from unusual for tenants to take in boarders to make ends meet, it was very rare for a white person to live in the same building as Black tenants, let alone the same unit. Bronkhurst’s profession was listed as a Baptist preacher. It is difficult to speculate on how he came to his living situation, but given the high Baptist population in San Juan Hill, he might have gravitated to the area for the purposes of evangelizing or work.

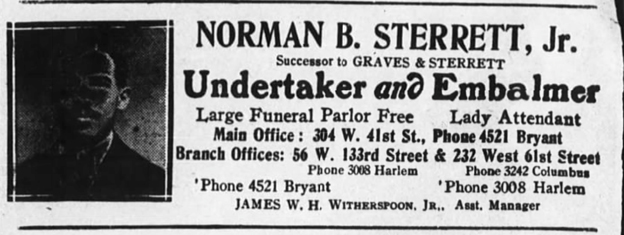

True of the many Black-owned funeral parlors in San Juan Hill, the profession was uniquely trusted and valued…

Like many residential structures throughout the city, the building was either originally intended for or altered to be mixed use, with the ground floor serving as a commercial space. As well, it wasn’t uncommon in similar buildings to have small businesses operate out of a tenant’s personal unit. For example, in 1906 a William H. Jackson made and sold a “magic oil” intended to relieve aches and pains out of his third-floor apartment. Various other businesses operated out of 232 West 61st Street over the years, with arguably the most reputable being a funeral parlor run by a Black man named Norman B. Sterrett, Jr. True of the many Black-owned funeral parlors in San Juan Hill, the profession was uniquely trusted and valued; white funeral homes would rarely serve Black patrons and, due to the emotional and necessary nature of the work, the possibility of having a Black undertaker and embalmer was considered particularly sacred. Further, it was a rare field in which Black proprietors could usually operate outside of a larger, white-connected business network. Sterrett’s family background was notable. He was born in South Carolina and the son of Norman Bascom Sterrett, founder and pastor of Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston. He was a graduate of the Avery Normal Institute and the Charles Reynaud School for Embalming before moving to New York City in 1907 and founding his own funeral parlor business. The business had several locations, both in San Juan Hill, West 41st Street, and West 133rd Street before fully relocating to Harlem during the Great Migration. Beyond funeral work, Skerrett was politically active and ran for New York State Legislature on the Equal Rights Party. When Sterrett died in 1944, he was hailed by newspapers as one of Harlem’s oldest serving morticians.

The building at 232 West 61st Street outlasted most other nineteenth-century structures in the surrounding area. It was eventually demolished and replaced with a parking lot by the 1950s. Today, a large office building stands on the site.

Resources:

1900 United States Federal Census, New York, Borough of Manhattan Enumeration District 449, Ward 19, image 40/56. Familysearch.com.

1910 United States Federal Census, New York, Borough of Manhattan Enumeration District 1651, Ward 22, image 17/32. Familysearch.com.

Caldwell, A.B. History of the American Negro. A.B. Caldwell Publishing Co. 1919.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/South_Carolina/0aYTAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

Finding Aid, Sterrett-Hodge Family Papers, Avery Research Center, College of Charleston, Charleston, SC, USA.

New York Age (New York, NY):

Nov. 1, 1906

Sep. 1, 1910

Jun. 12, 1926

Mar. 17, 1928

Apr. 8, 1944

New York Supreme Court. Records and Briefs, Vol. 195. Library of the New York Law Institute. 1967.

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, Vol. 116, No. 25 (3014) (December 19, 1925): 13.

Jessica Larson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is also the Joe and Wanda Corn Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum & National Museum of American History