211 West 64th Street

by Jessica Larson

At 211 West 64th Street stood a series of structures that, while seemingly unremarkable compared to the greater history of New York, made up part of the daily fabric of San Juan Hill. Over the years, the site reflected changing immigrant populations in the neighborhood and larger currents in American history.

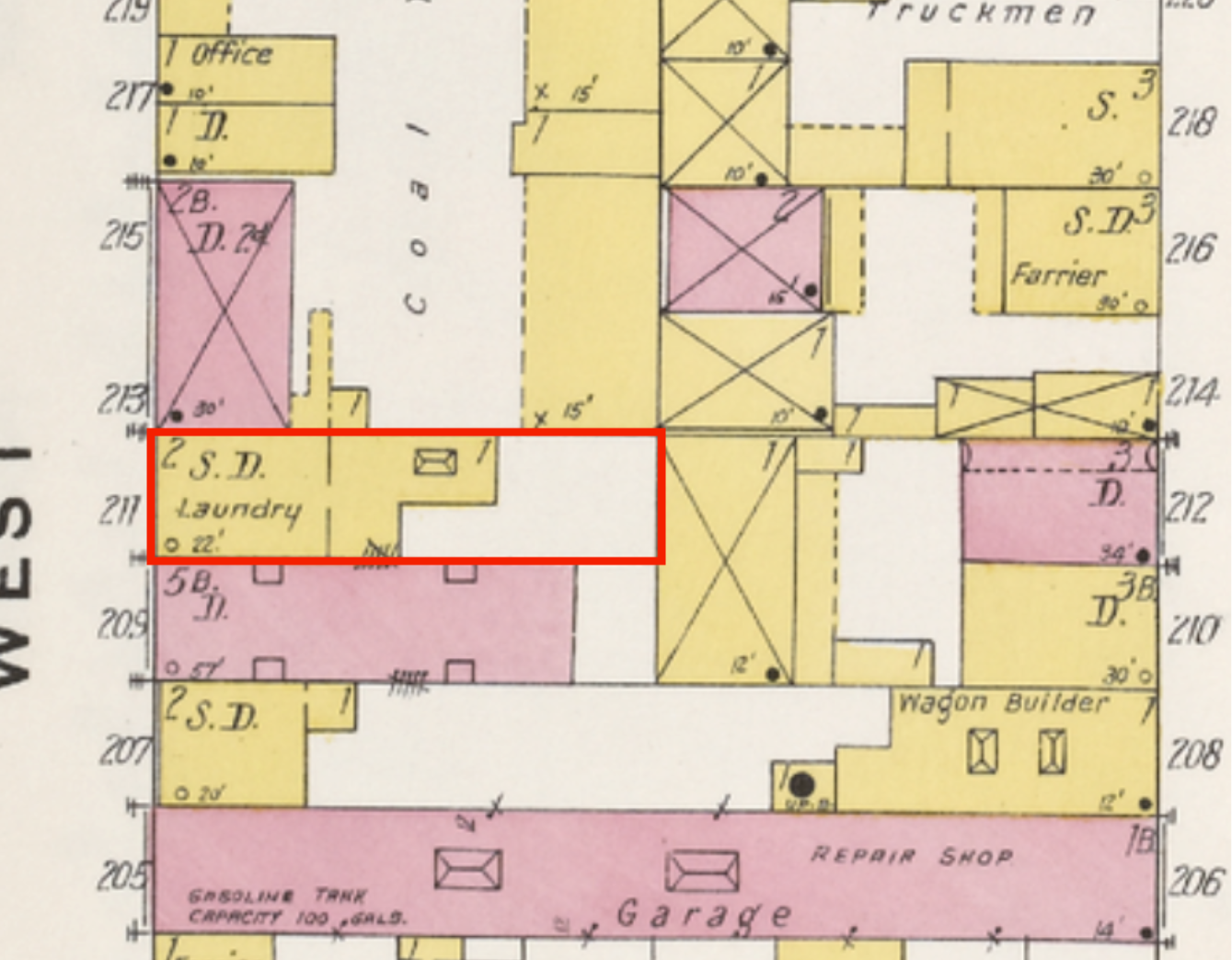

The first structure built on the lot was likely a two-story and basement frame building. While difficult to definitely conclude, a similar-looking structure is noted on the property in a fire insurance map from 1879. This accords with New York City’s building regulations; by 1882, wood-frame construction was illegal below 155th Street. Like other early homes built in the area before significant development, the structure might have served as a home–or second home–to those seeking to escape the pollution and congestion of Lower Manhattan. Alternatively, some homes were built to serve as housing for workers employed in the industries concentrated uptown or along the waterfront, though this is less likely given that the wood-frame structure at 211 West 64th Street seemingly stood alone, not as part of a larger development series. At some point between 1898 and 1907, a one-story extension was added to the building.

Boyle was a prominent sculptor who had established his career in Philadelphia, primarily depicting Native Americans.

As early as 1896, the Cashman family purchased the building. A woman named Catherine Cashman, a widow born in Ireland in 1860 who had immigrated to the U.S. in 1873 was listed as the head of household on the 1900 Federal Census, where she lived with her 13-year-old daughter Kattie and sister, 50-year-old Ellen O’Connor. Catherine had likely been married to a man named David Cashman, who had been noted in the papers for his legal troubles, mostly involving tax violations. How the Cashman’s used the property is a bit of a mystery; they likely converted it to mixed-use, with a portion of it serving as a commercial business. In 1898, a saloon was noted as existing on the site, and a laundry was listed on the property on a 1907 fire insurance map.

Catherine died in 1912, and the property was purchased by John J. Boyle for $9,500, which would be about $307,083 in 2024. Boyle himself lived on West 69th Street but used the house on West 64th Street as his studio. While largely forgotten today, Boyle was a prominent sculptor who had established his career in Philadelphia, primarily depicting Native Americans. Boyle was born in New York City but, like many of his contemporaries, pursued his education at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. While there, he studied under Thomas Eakins, one of the most celebrated American artists of the nineteenth century. Like fellow artists who focused on depictions of Native Americans such as George Catlin or Edward S. Curtis, Boyle’s work reinforced an image of Indigenous life as regressive, primitive, and soon to be gone, akin to North American species hunted to extinction like the buffalo. Boyle was working during the implementation of the Dawes Act or General Allotment Act of 1887, which authorized the confiscation of tribal and reservation land for private sale. Work by artists like Boyle helped normalize the mistreatment of Native peoples as something inevitable and necessary.

Boyle died in 1917, and the building soon became home to a live poultry shop owned by a man named Harry Bauman. While the earlier building was wood frame, photographs indicate that, when used as a poultry market, a new masonry building might have replaced the former, but it is difficult to definitively say based solely on a few photographs. While live poultry markets in Manhattan are much rarer today, these vendors were commonplace and important in the early twentieth century, particularly for Jewish inhabitants of the city–whom Bauman might have counted himself a member. By the 1930s, the Jewish population of the area was increasing. These markets were crucial for Jewish residents’ purchase of Kosher meat, and in the first few decades of the twentieth century, the city’s health inspectors had heavily cracked down on raising and keeping chickens in immigrant households.

Today, 211 West 64th Street is part of the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts. It stands across from the New York City Housing Authority’s Amsterdam Houses.

These vendors were commonplace and important in the early twentieth century, particularly for Jewish inhabitants of the city

Resources:

1900 United States Federal Census, New York, Borough of Manhattan Enumeration District 457, Election District 11, Ward 19, image 14/30. Familysearch.com.

“Bandits get $900 as Police Pursue Fake tip to Slayer.” New-York Tribune. January 08, 1922: p. 12

Catalogue of the Annual Exhibition of American Oil Paintings and Sculpture, Vol. 29. Art Institute of Chicago. 1916.

“Curiosities Left Over from Last Year.” The World. January 01, 1898: p. 7

“John J. Boyle, Sculptor.” New York Times. February 11, 1917: p. 23.

Levy, Florence H. American Art Directory, Vol. 10. American Federation of Arts. 1913.

Levy, Philip. Yard Birds: The Lives and Times of America’s Urban Chickens. University of Virginia Press. 2023.

“Mrs. Pollack Fined $10.” The World. May 12, 1896: p. 3

The Sun (New York, NY):

April 14, 1912

February 25, 1912.

“Stone Age in America.” Association for Public Art, January 2, 2024. https://www.associationforpublicart.org/artwork/stone-age-in-america/.

Jessica Larson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is also the Joe and Wanda Corn Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum & National Museum of American History