1855 Broadway

by Tom Miller

In May 1904, the architectural firm of Mulliken & Moeller filed plans for a “12-story brick and stone tenement” for the Jermyn Realty & Construction Co. to be constructed at the southwest corner of Broadway and 61st Street. The term “tenement” at the time referred to any multi-family structure, and the Jermyn “apartment hotel,” as described by the Record & Guide, would be nothing like the crowded, unhealthful buildings we associate with the word today.

On the contrary, the Beaux Arts style structure, completed in 1905, had “housekeeping apartments” (meaning they had kitchens) of ten rooms and three baths (one of which was reserved for servants). Clad in red brick and trimmed in limestone, its tripartite design included all the frothy French decorations associated with the style. The Jermyn Hotel cost its owners $575,000 to construct, or about $19.7 million by 2024 terms.

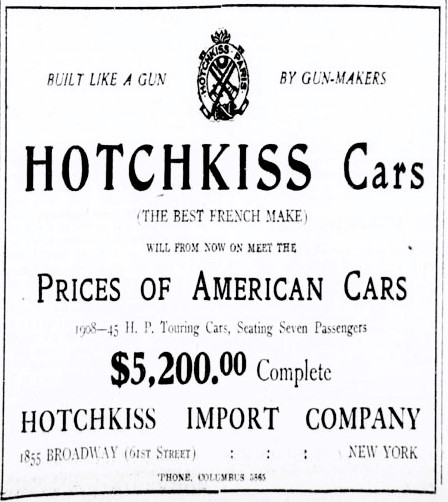

The residential entrance was at 10 West 61st Street, while commercial spaces occupied the ground floor of the Broadway side. The building sat within what was known as Automobile Row, so not surprisingly the commercial tenants were vehicle-related. Among them in 1908 was the Hotchkiss Import Company, which sold the French-made Hotchkiss automobiles. The firm’s catch phrase was “Built like a gun by gun-makers.” Another space was home to the sales room of the Pennsylvania Automotor Car Company.

Meanwhile, the residential tenants were professionals, like Edward Wilmot Chamberlain and his wife, the former Emily Beach. Chamberlain was an attorney and a member of the Social Reform and Twilight Clubs. Another early resident was John A. Lee, the chief plan examiner of the Manhattan Tenement House Department.

Max Goldsmith, a bachelor, lived here in 1908. He was a member of the wholesale silk firm of Hess, Goldsmith & Co. Living with him were two servants–his housekeeper and a maid—and an adult nephew. On the night of April 6, 1908, Goldsmith went to the theater. He returned to discover that his apartment had been burglarized and “a lot of valuable jewelry stolen,” according to The New York Times. Police suspected an inside job. The newspaper reported, “Once in the house [the thief] apparently knew exactly where to go, for the jewels were kept in a secret drawer in a dresser, that only a few members of the family are supposed to have known anything about.” The servants and nephew insisted they heard no one in the house during Goldsmith’s absence.

In 1909, the Jermyn Hotel became the Pasadena Apartments.

In 1909, the Jermyn Hotel became the Pasadena Apartments. No doubt its most colorful resident was David Lamar, known as the Wolf of Wall Street. Ostensibly a wealthy broker, he was one of New York’s most notorious conmen. His most visible victim to date was John D. Rockefeller, Jr. In 1899 he convinced the 25-year-old to purchase stock in U.S. Leather. Rockefeller borrowed the money from his father and lost nearly $1 million in the fraud. On May 4, 1909, Lamar’s wife “sent out a call for reporters to the newspapers,” reported The New York Times. “They found her in great excitement at her apartments in the Pasadena, 10 West Sixty-first Street. She vowed she was going to begin proceedings for a divorce against Lamar the very next day. She had discovered, she said, that he was keeping up a friendship with Marie Leonard, a chorus girl, at the Circle Theatre, just around the corner.” The Lamars, expectedly, moved out of the Pasadena soon afterward. (In 1913, David Lamar was indicted and charged with impersonating Congressman A. Mitchell Palmer.)

Newspaperman John Floyd Hume and his wife lived here at the time of the Lamar’s marital crisis. Mrs. Hume had been good friends with Tennessee Claflin, who was now Lady Cook of England, since they were children in Brooklyn. Whenever the Humes were abroad, they spent much time in Lady Cook’s company. In May 1910, Lady Cook arrived in New York as a houseguest of the Humes. Ten days later, her hosts were hauled into court by Lady Cook’s sister, Mrs. Mary Sparr of Brooklyn. Mary demanded that they produce her titled sister in court, charging that they “were keeping Lady Cook away from her family, and that Lady Cook was old, feeble, of advanced years, and large means.” She accused the Humes of having “undue influence” over her and were “endeavoring to obtain possession of her property.”

Lady Cook protested that it was her sister who was acting feebly. “People as they grow old sometimes get strange ideas, you understand,” she told a reporter. “When I am in New York I sometimes stay here and sometimes with other friends, and I don’t know any reason why I shouldn’t. I’m going away soon on a lecture tour, and it’s ridiculous to say that anyone is putting any restraint on me. Do I look like it?”

Mrs. Sparr’s case was dismissed.

Two new commercial tenants came in 1911. The Mitchell Car Company opened the “Mitchell Branch” on November 2, that year. The firm’s announcement said, “we have built a handsome and commodious sales and display room. A few blocks away, on West 55th street, we have likewise created a six story and basement Service Building.” The other tenant was J. Mora Boyle, who dealt in Midland, Correja and Bergdoll motorcars.

Living in the building at the time was A. Maynard Lyon and his wife, the former Ann Maria Collins. The elderly couple was married in 1846. A retired real estate dealer, he was a philanthropist and writer of poems and hymns. The Sun described him as “a wonderfully well-preserved man. He is in possession of all his faculties and still looks after his extensive business interests.”

In 1912, the 94-year-old decided to sail to Britain, but he could not convince Anna Maria to accompany him, since she had “a fear of ocean travel,” according to The Sun. Instead, he arranged for their daughter, Mrs. Lucina McLaughlin and her maid to come along. “They will have a suite of rooms on the big ship,” said the newspaper. The article explained, “The elderly traveler says he is going to nose around Eton College and will spend much of his time at Harrow-on-Hill, a college that was founded by one of his ancestors. He will also go to Rugby.” Mostly, however, he was seeking inspiration for new poems and songs.

Like Max Goldsmith, attorney Harold Curtis Bullard was a bachelor. An 1884 graduate of Dartmouth College, he had never married because of his mother’s “physical infirmity,” according to The New York Times. She died in 1911, freeing Bullard to seek a wife. And it did not take him long to find one. On December 29, 1912, The New York Times reported that he and Mrs. Helen Rollins had been married in the chapel of the General Theological Seminary five days earlier. “Mr. Bullard and his bride were sweethearts in their youth,” said the article. The Pasadena would see less of Harold Curtis Bullard, now. “The couple will spend several months traveling, and plan to spend six months of each year in Paris.” They were still living here when Harold Bullard died on December 16, 1916, at the age of 55.

An advertisement for the Pasadena in October 1914 listed the rent for a 10-room, “especially attractive,” apartment at $2,700 per year, or about $6,800 a month in today’s terms. Only a year later, it appears that some of the sprawling suites had been divided. An advertisement in The Sun listed apartments of “2, 4, 7, 8 & 10 rooms & 1, 2, & 3 baths.”

A factory branch of the Marmon-New York Co. opened in March 1914. The opening ad promised, “we will gladly furnish every service for present and prospective owners of Marmon Cars.”

Another colorful resident of the Pasadena was George Francis Considine. He lived here with his second wife, former dancer Aimee Angeles. George was “known in sporting circles the world over,’ according to The Evening World. The newspaper said during his time as proprietor of the Hotel Metropole on Broadway at 42nd Street, he became friends with “all the theatrical and sporting celebrities of the years between 1901 and 1910,” said the newspaper. Among his closest friends was “Big Tim” Sullivan, the prizefighter. In 1910 he opened the new Metropole, near the former hotel. “He retained his interest in that hotel until the shooting of Herman Rosenthal in July, 1912, when he gave it up because of the notoriety that crime gave to the place.”

In 1966, as the sweeping Lincoln Square urban renewal project overtook the neighborhood, the structure was unrecognizably altered by architect Horace Ginsbern into the offices of the State Narcotic Addition Control Commission.

Three years after Harold Curtis Bullard’s death, Helen Rollins Bullard remarried. On December 28, 1919, the New York Herald reported she had wed Lieutenant-Commander Arthur W. Sears of the U.S. Navy’s Atlantic Fleet in the Rutgers Presbyterian Church. A reception and dinner were held in Helen’s apartment here.

Like Aimee Angeles, resident Janet Jackson was a dancer. She made her first appearance in 1912 when she was 18 years old. The New York Herald noted, on July 11, 1920, “Later she made a study of artistic dancing and with Miss Ruth Cramer developed what they called ‘play dances.’” The day before that article, Janet Jackson had married artist Charles Leslie Thrasher in St. Stephen’s Church. The two met when she posed for a figure in a mural he was painting in Wilmington, Delaware. His talent had proved useful when America entered World War I. The New York Herald said he “was one of the first Americans to do camouflage work in France.”

By 1941 the name of the building had changed again. It was now the Midtown Hotel. In 1966, as the sweeping Lincoln Square urban renewal project overtook the neighborhood, the structure was unrecognizably altered by architect Horace Ginsbern into the offices of the State Narcotic Addition Control Commission. Ginsburn’s modern glass curtain façade gave no hint of the 1904 bones beneath. Sharing space in the building with the state offices were the city’s Office of Cultural Affairs.

Then, in 1975, the New York Institute of Technology purchased the property and altered the offices into classrooms, lecture rooms and other educational spaces. The facility was in contract to sell the building in 2019, and retain a short-term lease. With the onset of the Covid pandemic all plans to vacate ceased and the deal did not close. Still, its survival is shaky. When the New York Institute of Technology first offered it for sale, a marketer said, “you could tear it down and build condos with some park views.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Keep the spirit of San Juan Hill alive! Support this local nonprofit at 1855 Broadway: