1841 Broadway – The Cova Building

by Tom Miller

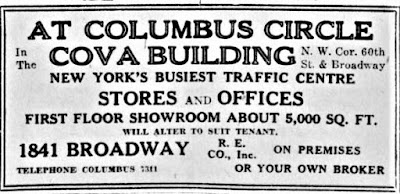

In 1921 Brooklyn lawyer Algernon I. Nova recognized the financial potential in the northwest corner of Broadway and 60th Street. The two-story building there faced bustling Columbus Circle and sat along the stretch of Broadway known as Automobile Row, named after the scores of auto-related businesses that lined the thoroughfare from Times Square to 72nd Street. And ten transit lines came together at the Columbus Circle subway station, steps away from the site.

He convinced two other investors, Alexander Cohen and Isidor Staub to join him in forming the 1841 Broadway Realty Estate Company, and then laid plans for a new building.

The syndicate signed a 63-year lease on the property that fall with a total rent of $2.52 million. On October 21, 1921 the New-York Tribune commented that the newly-formed firm “plans to improve the site with an eight-story structure, which will doubtless be devoted largely to the automobile trade.”

The developers proceeded cautiously, however. They hired the architectural firm of B. H. and C. N. Whinston (whose offices were conveniently located at No. 2 Columbus Circle) to design the structure in two stages.

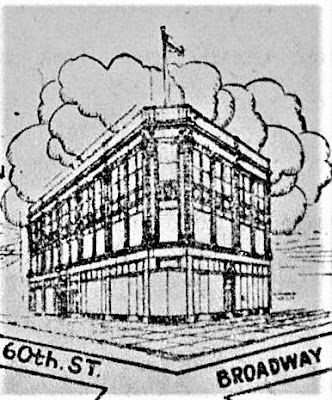

The first, a three-story structure, was completed in the fall of 1922. Its corner was chamfered, softening the visual angle while making the interior spaces more effective for showrooms or offices. The New York Herald wrote, “The facade of the building is of limestone and glazed terra cotta with copper and bronze window frames and entrances.” The ground floor featured large expanses of plate glass, above which two-story terra cotta piers terminated in elaborate Corinthian capitals. A parapet crowned the cornice.

Leases were signed well before the building was completed, prompting the developers to push their contractors. On October 1, 1922 the New-York Tribune noted “The owner has urged speed in order to meet the requests of tenants for early occupancy.” The success in leasing the spaces may have also hurried along the start of the second phase.

“It is possible that the height of the building will be increased shortly by building additional floors, because of the demand for modern space in the district,” said the article. “The building has been planned and designed to carry additional floors. At the time construction work was started it was the opinion that these extra floors would not be required for a few years at least.”

Opened on November 1, it was called the Cova Building. Its owners marketed it as “New, Modern, Fireproof,” and boasted that its Columbus Circle location was “New York’s busiest traffic centre.”

Among the first tenants was Ned Wayburn, who took the vast Broadway-facing space on the third floor. The producer of the Ziegfeld Follies, among other shows, he called himself the “World’s Greatest Authority on Stage Dancing.”

He opened his “magnificent new studios of stage dancing” here, advertising to hopeful stars that as well as receiving professional training, “you will incidentally have the privilege of looking over the most luxurious and professional Stage Dance Salon in the world, arranged and decorated with all the technical skill of a master of production.” The space held private studios, large class studios, a professional stage with footlights, dressing rooms, and “shower, baths and lockers.”

Crossman wrote, “Nine stories have just been added, to make it a twelve-story building. Construction work, both exterior and interior, was completed within three months.”

Acceptance into Ned Wayburn’s classes required an audition. An ad in Variety early in 1923 said “A minimum of 100 will be interview and a considerable number given initial training to find star material.”

The students in Wayburn’s studio had to deal with hammering, banging and other associated noises of construction as the upper floors got underway several months later.

On October 1, 1922 only a month after the Cova Building opened, The New York Herald had reported “Negotiations are under way for a long term lease by a commercial establishment on five additional floors in the new Cova Building…Negotiations are also under way for leasing the basement space of approximately 7,000 feet to a restaurant.”

Wayburn’s dance classes apparently forged on valiantly and on December 26, 1923 The Morning Telegraph announced “Ned Wayburn will present an ‘Advanced Pupils’ Frolic’ at his Demi-Tasse Theatre in his studios at 1841 Broadway on Saturday night of next week. It will be presented entirely by students in his advanced classes, whom he calls ‘stars in the making.'” Broadway managers had been invited to the show.

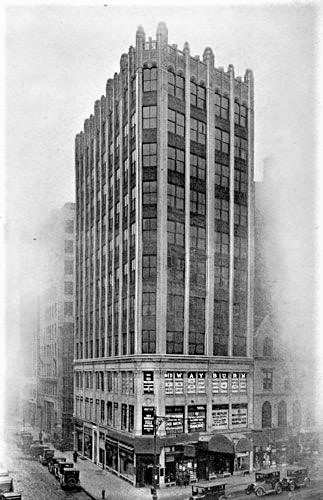

The upper floors were completed the following year. On the reverse of his photograph of the enlarged building on December 26, 1924, a photographer named Crossman wrote, “Nine stories have just been added, to make it a twelve-story building. Construction work, both exterior and interior, was completed within three months.”

What had been an easily overlooked structure now demanded attention. Corinthian capitals, rosettes and a fussy cartouche above the second floor gave way to Jazz Age Art Deco. That the same architects were responsible for the two highly disparate designs is astounding. The beige brick piers of the upper stories framed intricate Art Deco pressed metal spandrel panels at every floor. The parapet exploded in a crown of modern pinnacles.

The sprawling basement space became a “restaurant with dancing.” What appears to be the only auto-related tenant was Copp Sales Company, Inc., in the building by 1925. The firm marketed car glass, advertising in The New York Sun on November 11 that year, “If you want to buy ‘That Particular make of Car’ and the closed model is too costly–Buy an Open Car and have it equipped with GlassMobile. The only Practical, Year-Around Glass Windows. On or Off in 4 Minutes.”

Ned Wayburn would remain on the third floor through 1927. He shared the building with an extraordinary variety of tenants. In 1925 builder and contractor Harrison Realty Corporation took offices; the same year that N. Y. Corliss Limb Spec. Co. advertised its Laced Stocking. Saying it “laces like a legging” the firm promised the item would cure leg troubles like varicose veins and “open or swollen limbs.”

In 1926 three firms (which were most likely run by the same owner) advertised questionable products, at least when judged through 21st century lenses. The Scientific Research Laboratories marketed Dr. Folt’s Soap which promised to “reduce your ankles and legs.” An advertisement in the Buffalo Courier that year began “Any fat woman can wear short skirts IF she reduces her legs with the simple, easy formula given below.” That formula was to buy a 50 cent bar of Dr. Folt’s Soap, and “use it every night and morning for a few days. All you need to do is to make a good lather, rub it on the fat parts you want to reduce then wash off.”

Another ad that year in The Daily Star promised that Dr. Folt’s Soap would reduce “arms, legs, hips, [and] double chins.” To prove its point, the ad pictured a before and after sketch of a user’s remarkable transformation.

The Scientific Co. promised women that to clear a poor complexion, they need only “Try some ‘French Laxative Pellets.'” Comparing the body to a house, an ad read “If you clean the pipes the water will flow through it clean and pure.” And another firm, almost assuredly connected with the others, was Sangrina Co., which promised customers they could “get thin without weakening diets or strenuous exercises…If your friends call you ‘fatty’ and if you are not popular–you should try SAN-GRI-NA.”

A small firm marketing apparently just one item was Wonder Products. It was looking for traveling salesmen in 1927 to sell the Wonder Cap. The notice assured it was a “money-maker” and that “housewives buy one to a dozen.”

In December 1933 Prohibition came to an end and Irish-born Patrick J. Grimes was prepared. He opened his retail wine and liquor store in the Cova Building practically the moment that the repeal went into effect. On December 23 The Irish-American Advocate wrote “John C. O’Connor, editor and publisher of this paper, played the roll of Santa Claus to his editorial staff on Monday. Each received a handsome package made up at the P. J. Grimes’ family wine and liquor warehouse, 1841 Broadway at 60th street.”

O’Connor credited his mention for the success of the store that holiday season. Calling the proprietor “my friend Paddy Grimes,” he reported on January 6, 1934 that “His wine store was crowded all through the holidays.”

Other tenants included Hammond & Company, gold dealers. While some New Yorkers struggled for extra money during the Depression years, the firm suggested “Get the cash to buy your Christmas gifts with or to use for personal or home needs out of the old gold tucked away in bureau drawers, trunks or other safe keeping places.”

In 1936 architect William I. Holhauser ran his office from the building. That year he designed, for instance, a six-story apartment building in Yonkers. In 1941 he was working with the city in designing housing units for the influx of “workers in defense projects in Yonkers and the metropolitan area,” explained The Herald Statesman on December 11.

Another architect, Seymour R. Joseph, was in the building by 1949. That year he won first prize in the New York State Division of Housing for his design of a “home for the average wage earner.”

In the meantime the corner store had become home to the Columbus Circle Pharmacy in 1939, not coincidentally owned by Alexander Cohen, one of the partners in the syndicate which erected the building.

Around the same time The Summer Playschools Association moved in. It was founded in 1916 “expressly to meet the refugee children problem,” according to News Of New York. The organization ran “playschools” within the otherwise closed public schools during the summer months.

In 2008, the Cova Building was deemed a “National Register Eligible” building.

Less commendable in his goals was John B. Kepner, head of the Keystone Organization which was in the Cova Building in 1941. His connection with the auto industry was on the wrong side of the law. On August 22, 1941 The New York Sun reported on the arrest of Nicholas Pugliese who, over a span of five years, had stolen 500 cars. The one-man aut0-theft ring confessed to District Attorney William O’Dwyer that “he sold 300 of the cars to John B. Kepner.”

The wide variety of tenants continued. In 1944 the head offices of Safeway Grocery Stores was here; and by 1946 the American Express Catholic Travel League was operating from the building. That organization would remain for years, arranging tours throughout the world.

The publishing firm Play Schools Association was also here at the time. In 1942 it released A Child’s Way of Growing Up and A Yardstick of Growth. It would remain in the building at least through 1958.

Music publishers called the Cova Building home beginning around 1961 when Plymouth Music Co. moved in. Atlantic Records and ATCO records were in the building by 1969. Atlantic Records remained into the 1990’s. The presence of those firms may have prompted The Jazz Composer’s Orchestra to rent space in 1971. An outgrowth of the 1964 The Jazz Composer’s Guild, it produced its own albums and staged concerts.

The mish-mash of tenants in the 1970’s included the New York Council of Environmental Advisers, which ran its “Keep New York State Clean” campaign from here; and Parents Anonymous, a self-help group for those who recognized that they “were abusive parents and wanted to do something about it,” as described by its head, former Family Court judge Gertrude M. Bacon.

Another organization with a serious purpose was the Council on Interracial Books here from about 1980 through 1994. Its publication Guidelines for Selecting Bias-Free Textbooks and Storybooks was “meant to assist parents and educators in identifying books for children that are free of sexism, racism, ageism, and classism.” Another of its publications was the Interracial Books for Children Bulletin.

As the century drew to a close the Center for the Study of Anorexia and Bulimia operated from the building, as well.

In 2008, the Cova Building was deemed a “National Register Eligible” building. As Fordman University sought to expand its Upper West Side campus, the New York Office of Parks, Recreation & Historic Preservation proclaimed that the Cova Building “is significant as an intact example of early 20th century commercial design.”

Despite that, or possibly because of it, in October 2013 the owners spent more than half a million dollars to strip off the striking Art Deco spandrel panels and the terra cotta ornamentation and replace them with featureless composite stone panels. The ground floor was given a cladding of tiles more expected on a Canal Street electronics or plastics outlet.

And then in 2019 plans were unveiled for a 24-story structure to replace the desecrated Cova Building.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com