107 West 64th Street

by Jessica Larson

In the early twentieth century, the brownstone at 107 West 64th Street was home to several notable women artists. Built in the 1880s, this structure was developed alongside the same residential buildings built on sites between 104-123 West 64th Street. The building was four stories and a basement with a two-story and basement extension in the rear lot. Typical of brownstones built at the time, the building would have been constructed speculatively with the expectation that the neighborhood would soon attract new and likely middle-class residents. As opposed to the multi-unit tenements that the area was most notorious for later, these brownstones were only intended to house a single family, possibly with one or a few servants. In the 1880s, before the area became known as San Juan Hill, this was true; by 1900, when the demographics of the neighborhood were just beginning to change, the building was home to two young French families (likely related or perhaps family acquaintances from back home), a small family from New York, and a 45-year-old Virginian woman and her daughter, listed as boarders. It is possible, given that numerous families were occupying the brownstone simultaneously, that it was subdivided, which was a common practice and still true of many of New York City’s brownstones.

Like many women of her social standing during the Progressive Era, she was active in charitable and reform clubs, particularly one called the Daughters of Lafayette Post

In the 1900 Federal Census, one of the tenants from New York is listed as a “Mabel Dukins.” Also in 1900, the artist Mabel Harrison Duncan is listed as residing at the address in various art journals. This was likely the same person – either her name was mistranscribed in the census, she married a “Duncan” later, or she went by an alternative name during her artistic career. Not much is known about Duncan today. By 1907, she was enrolled as a first-year student in Columbia University’s Teachers College, with a special focus on Fine Arts. She later taught at Washington Irving High School in Tarrytown, New York. Like many women of her social standing during the Progressive Era, she was active in charitable and reform clubs, particularly one called the Daughters of Lafayette Post, which focused broadly on supporting veterans’ initiatives. The few surviving artworks and listings in exhibition records demonstrate her interest in still-life painting, which was a common subject for women artists at the time. She later channeled this training and practice into work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where she was a member and regularly lectured on the collections from topics ranging as diverse as imperial art from China to ceramics of the Mediterranean.

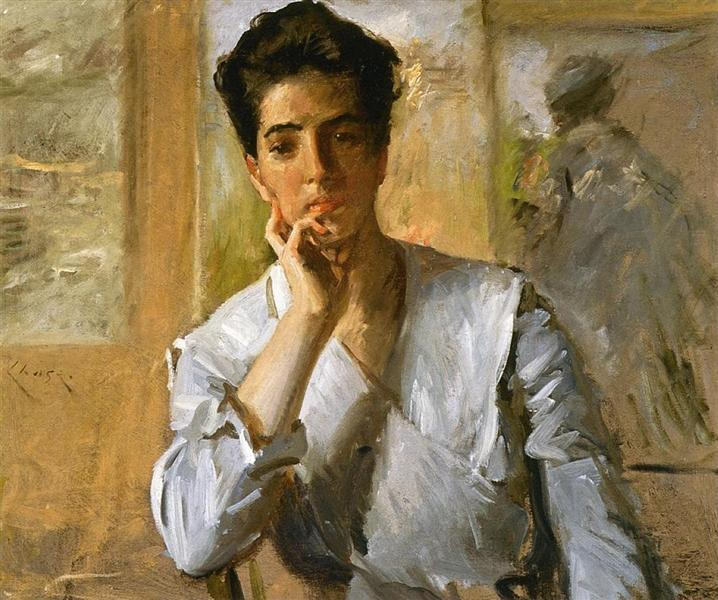

By 1907, another woman artist, Freeman Clark, resided at 107 West 64th Street. Perhaps the two women knew each other. Born Kate Freeman Clark in Holly Springs, Mississippi, she adopted just “Freeman Clark” professionally so that her gender would not be widely known while exhibiting; although there were certainly prominent women artists at the time, being a woman was still a massive impediment to success in the art world. Her own family was largely against her pursuing an artistic career, warning her that she should avoid spheres reserved for men. Clark’s childhood was spent in Mississippi, but her family relocated to New York City while she was a teenager. While attending the Art Students League, Clark studied under prominent American artist William Merritt Chase and soon began to exhibit widely throughout the East Coast. Her works evidence Chase’s influence on her style, with her paintings strongly resembling contemporary works produced by American and French Impressionists. Curiously, Clark is not listed on the 1910 Federal Census as residing in the building, yet the address continued to be associated with her in artist directories until at least 1919. Five years later, in 1924, Clark returned to Mississippi and seemingly ceased to exhibit or participate in the art world. The reasons for her reclusivity are unknown, but it is speculated that Chase’s death in 1916 took an enormous toll on Clark. Today, the Kate Freeman Clark Art Gallery, located next to her former home in Holly Springs, holds over 1,000 of her paintings.

The building at 107 West 64th Street was demolished as part of the construction of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, which began in 1955.

Born Kate Freeman Clark in Holly Springs, Mississippi, she adopted just “Freeman Clark” professionally so that her gender would not be widely known while exhibiting

Resources:

1900 United States Federal Census, New York, Borough of Manhattan Enumeration District 455, Election District 10, Ward 19, image 20/38. Familysearch.com.

Board of Education. Bulletin of High Points In the Work of the High Schools in New York City, Vol. 2, no. 1. Board of Education. 1920.

Brown, Carolyn J. The Artist’s Sketch: A Biography of Painter Kate Freeman Clark. University Press of Mississippi. 2017.

Corcoran Gallery of Art. Fifth Exhibition of Oil Paintings by Contemporary American Artists, December 15, 1914 Until January 24, 1915 (Inclusive). W.F. Roberts Co. 1914.

Columbia University in the City of New York. Catalogue and General Announcement, 1906-1907. Columbia University. 1907.

“The Daughters of Lafayette Post, No. 140, G.A.R.” New York Times. September 4, 1898: p. 28.

Levy, Florence N. American Art Journal, 1900-1901, Vol. 3. Noyes, Platt, and Co. 1900.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Annual Report of the Trustees, Vol. 58-61. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1928.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Vol. 23, no. 1. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1928.

National Academy of Design. Winter Exhibition Illustrated Catalogue. The Knickerbocker Press. 1911.

Jessica Larson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is also the Joe and Wanda Corn Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum & National Museum of American History