Scotch Presbyterian Church

2-10 West 96th Street

by Tom Miller

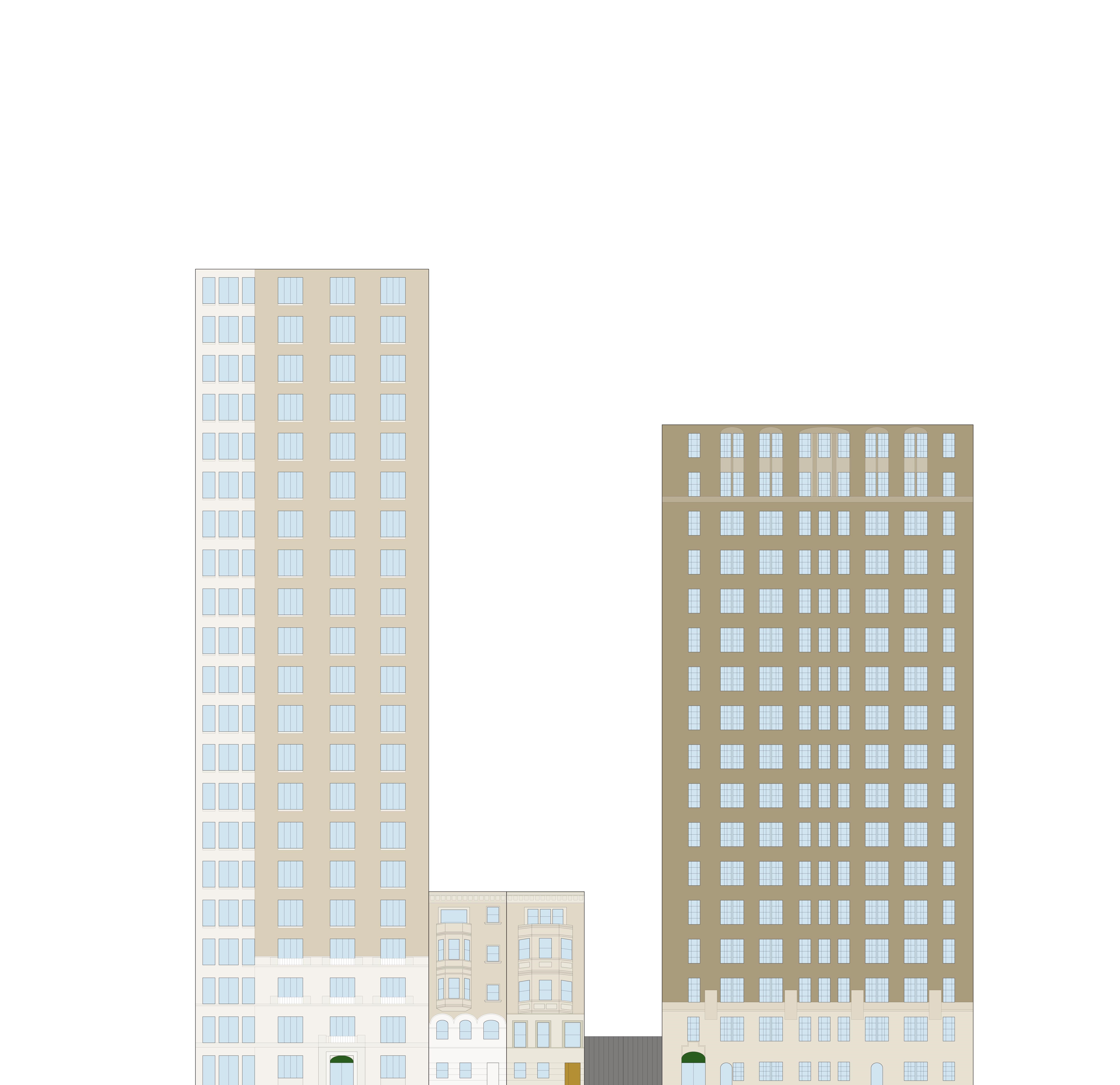

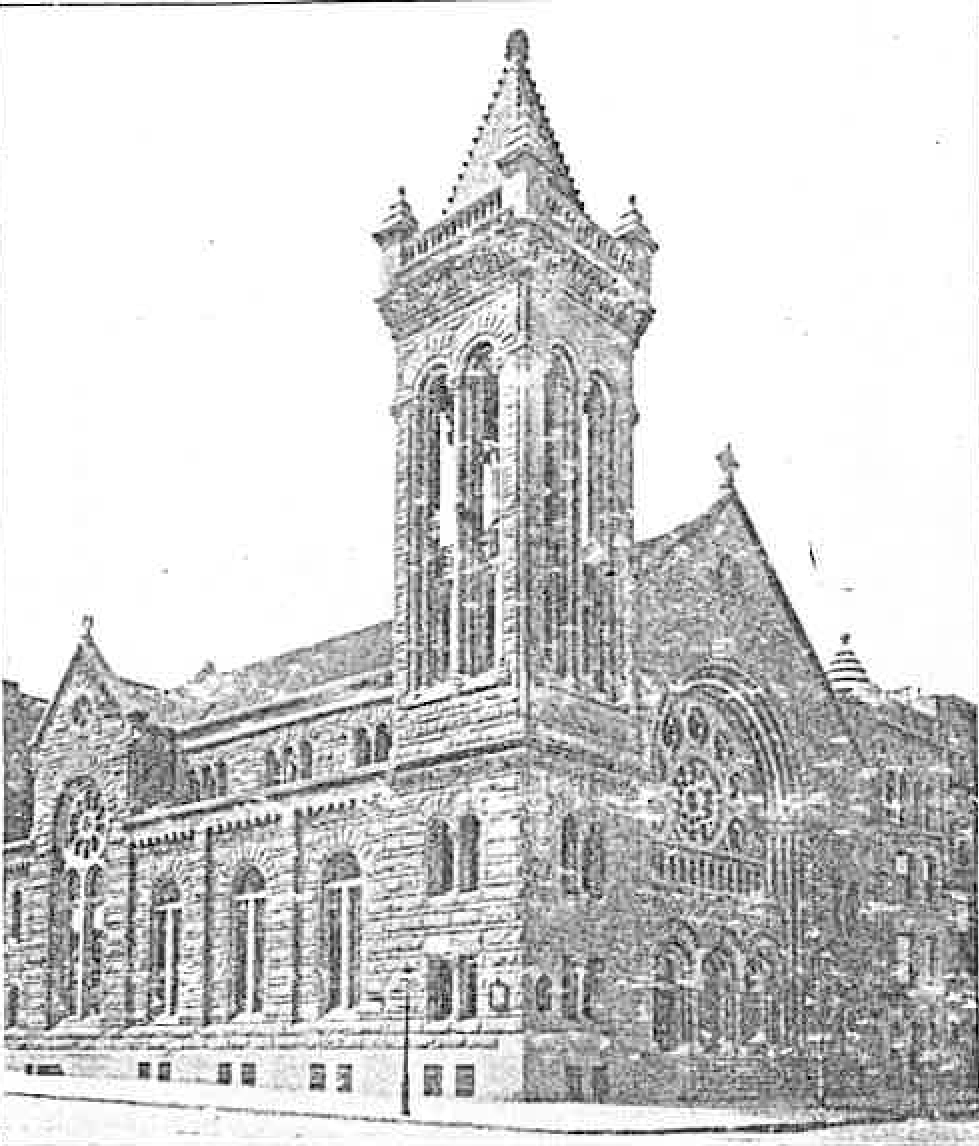

The Sicilian Romanesque-style Scotch Presbyterian Church, designed by William H. Hume, had stood at the southwest corner of 96th Street and Central Park West for 34 years in 1928 when its congregation made a decisive move. For several years, the concept of “skyscraper churches” had changed how urban congregations remained financially afloat. Traditional church structures were replaced with high-rise apartment buildings that incorporated the religious spaces within.

The Scotch Presbyterian Church hired architect Rosario Candela to design a 16-story apartment building on the site of its venerable structure. Completed in 1929, it was a blend of neo-Renaissance and neo-Gothic styles—the latter appearing most noticeably in the two-story stone base, and the soaring, four-story church entrance on West 96th Street. Here the three entrances sat within Gothic arches. On the side of the main entrance, buttresses rose to flank a large stained glass window.

The residential entrance, at 360 Central Park West sat below a stepped, square-headed drip molding. The brick-clad, 12-story midsection was unadorned. Rosario returned to Gothic embellishments on the top section.

The church portion of the building included a gymnasium and meeting space in the basement, the sanctuary on the first and second floors, and a school on the third. On the residential side, an advertisement offered apartments of two, three, or four rooms starting at $1,500 per year, or about $2,250 a month by 2024 conversion.

The widowed Eliza W. Sanford was among the initial residents. She no doubt raised eyebrows city-wide when newspapers reported on December 5, 1929, that the 69-year-old had adopted her 27-year-old chauffeur, Baronig Baron. The adoption was approved in the Orphan’s Court. The Standard Union said, “Mrs. Sanford, who is reputed to be worth more than $1,000,000, stated in the adoption papers that she has $750,000 which she will leave to her adopted son upon her death.”

The Armenian-born groom had come to America shortly after World War I, during which both his parents were killed. He had been Mrs. Sanford’s chauffeur for several years. The Standard Union mentioned, “So far as can be learned here, Baron is single.”

The church portion of the building included a gymnasium and meeting space in the basement, the sanctuary on the first and second floors, and a school on the third.

The financially comfortable tenants of 360 Central Park West had garnered their fortunes through widely varied means. Bachelor Michael Regan, a native of Limerick, Ireland, had conducted a hotel and bar at the corner of Clarkson and West Streets for years. Never forgetting his roots, the Irish American Advocate said, “He was influential and undefatigable [sic] in getting Irishmen jobs.” Upon his death in April 1934, he left $95,000 to Catholic charities, more than $2 million today.

Addrich J. Dale acquired his wealth by dealing in German-made Meerschaum pipes starting in 1897. The war with Germany necessarily halted his importing, so he opened his own factory in Brooklyn making briar pipes. He and his wife, Rosa, moved into 360 Central Park West after his retirement as president of Addrich J. Dale, Inc. in 1930.

Mary Gran moved into an 11th-floor apartment in 1934. Keeping mostly to herself, the Daily News said that neighbors knew her only as a teacher. In fact, when she moved in, the 49-year-old had taught sewing and dressmaking in the public school system since January 3, 1905. On the evening of September 8, 1941, the night before the first day of school, she did not put last-minute touches on her preparations for the next day’s classes. “Instead,” reported the New York Evening Post, “she took a vegetable-freshener box from her electric refrigerator and in it carefully packed a complete outfit of clothing—her very best.” She then sat at her dining room table and wrote a label for the box: “Dress and underwear for the body of Mary Gran.” She included a list of the telephone numbers of the Riverside Chapel Funeral Home, the Chief Medical Examiner, and the Teachers’ Retirement Fund.

The Daily News reported, “At 5:30 A.M. yesterday, accumulated gas in her kitchen was ignited by the pilot light of her gas stove. An explosion wrecked the apartment.” The Evening Post added that the blast “shattered the windows and glassware of Miss Gran’s apartment and shook the rest of the building.” Her body was found by building attendants.

World War II saw female residents of the building offering their support to the war effort. When Mayor LaGuardia appealed for funds for the “purchase of armbands, lapel buttons and other equipment for the city’s air raid wardens,” Lillian Rubin wrote to him saying, “I am hereby offering my services in any capacity for office or secretarial work for civilian defense. I would deem it a special favor if I could work for you or for Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt.”

Carolyn M. Mossner went a bit further, joining the Woman’s Army Corps. She and her fellow WACs landed in Britain in July 1943. With the sexism typical of the period, The New York Evening Sun called them on August 7, “the world’s most beautiful army.”

Al Becher and his family lived here in 1947. He was described by The Brooklyn Daily Eagle as “a wealthy furrier” who lived in a “swanky” apartment. On the night of June 25, two robbers, “well dressed and apparently between 16 and 20,” held the family at gunpoint and “systematically ransacked the four-room apartment, taking an hour to do so,” according to the newspaper. They made off with $15,000 in jewelry and $250 in cash.

Three months later, the apartment of Edmund and Mercedes Fayle would be the scene of a similar crime. Fayle was port captain of the Amerian Export Lines. The couple’s son, Lieutenant Commander Edward Fayle, was stationed at Floyd Bennett Field. On the afternoon of September 8, he and his wife brought their baby daughter, Susan Antoinette, to visit. When they entered the apartment, they realized they had interrupted an armed robbery.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle said, “The bandit pair promptly got to work on the pockets of the new arrivals, when Susan Antoinette, who is 11 months old and not partial to strangers, began to cry.” One of the robbers asked, “What’s the matter with her?” He was told it was past time for her orange juice. The Kingston Whig-Standard reported, “While one remained to guard the Fayles, the other went to the kitchen, squeezed an orange and fed the baby. Then they trussed Fayle and put him in the closet, tied his wife to a chair with the baby in her lap, and left with $500 in cash and jewelry.”

The thieving duo was quickly named the Orange Juice Robbers by newspapers. Just over two weeks later, on September 23, Mercedes Fayle was called to the West 100th Street police station. There she identified 21-year-old William Schmitt as one of the robbers. The other, Joseph DeBlisio, was captured soon afterward.

Throughout the ensuing decades, the building continued to see a wide variety of tenants. In the mid-1950s, vocalist Marianne Skura lived and taught here. Marketing herself as a “specialist in correct voice building,” she also sang professionally in opera, concert work, and radio.

“The bandit pair promptly got to work on the pockets of the new arrivals, when Susan Antoinette, who is 11 months old and not partial to strangers, began to cry.”

A fascinating resident at the same time was Dr. Thomas W. Matthews, “reported to be the only Negro outside Harlem heading a city hospital department,” according to The New York Age on September 13, 1958. Matthews was director of the departments of neurosurgery and electro-encephalography at Coney Island Hospital.

Matthews tackled a puzzling case in 1957. John H. Sheppard, Jr. was referred to him by Dr. Aaron G. Wells because of severe abdominal, spine, and head pains he had suffered for three years. Sheppard had been a private car steward with the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad since 1940. On May 9, 1954, he was serving in the private car of the railroad’s president when a yard engine plowed into the end of the car. Sheppard was knocked unconscious and later diagnosed with seven fractured ribs, a punctured lung, and multiple muscle injuries.

After his discharge from the hospital, his pains continued. Even after examination by specialists at two of New England’s more noted medical institutions, Sheppard could not get satisfaction. The experts all diagnosed pancreatis, an ailment he suffered before the accident.

On January 25, 1958, The New York Age reported that Dr. Matthews found the problem was nerve pressure and advised an operation. Following the operation, Sheppard was pain free, although he had to wear a spinal brace. He was awarded $80,000 damages against the railroad, thanks to Matthews’s diagnosis.

Among Dr. Thomas Matthews’s neighbors was Assistant District Attorney Theodore S. Weiss, who had been active in Democratic politics since 1954. On January 24, 1959, The New York Age reported that he had resigned “in order to be able to engage wholeheartedly in the battle against Tammany Hall.” The article said he intended to run for District Leadership of the 5th Assembly District North. Ted Weiss would go on to serve in the United States House of Representatives from 1977 until his death in 1992.

In 2017, 360 Central Park West was converted to condominiums. The church (now called Second Presbyterian) still occupies its soaring space on West 96th Street.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Be a part of history!

Stay local to support the nonprofit currently at 360 Central Park West/ 2-10 West 96th Street:

NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project Site History