Saint Ignatius of Antioch Episcopal Church

552 West End Avenue

by Tom Miller

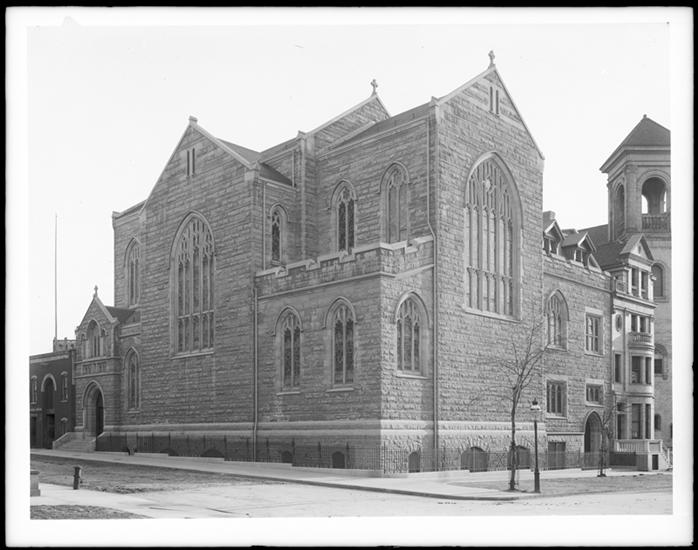

The Episcopal Parish of St. Ignatius of Antioch had worshiped in the former Dutch Reformed Church at 54-56 West 40th Street since just after its founding in 1871. As the turn of the century approached, its site across from Bryant Park was increasingly commercial. On March 9, 1901, the Real Estate Record & Guide reported, “St. Ignatius, Protestant Episcopal Church, Rev. Arthur Ritchie, pastor…is the buyer of the plot, 75×100, at the southeast corner of West End av. and 87th st….A new church will be erected on the site, for which Charles C. Haight…is the architect.”

The choice of site was a surprise to many since the proposed structure would snuggle up against St. Paul’s Methodist Church, constructed five years earlier. The New-York Tribune remarked on November 11, 1901, “When St. Ignatius’s Episcopal Church is completed…the West End-ave. block between Eighty-sixth and Eighty-seventh sts. will present a unique appearance. It will be wholly covered by two churches, both of them as distinct in architecture as are to be found in America.”

Indeed, Robert H. Robertson’s St. Paul’s was an architectural novelty, the New-York Tribune calling it “a radical departure in ecclesiastic building.” Haight’s St. Ignatius, in the English Perpendicular Gothic style, would be much different, yet would “present an appearance quite as unusual as its near neighbor,” according to the journalist. The architect deftly handled the potentially blocky mass of the structure with two-story gables and immense Gothic openings. The New-York Tribune noted, “Most of the memorials of the old church in West Fortieth-st. will adorn the interior.”

Haight filed plans on August 2, 1901. The cost of construction for the church and parish house was estimated at $80,000–just over $2.5 million in today’s money. Much of that amount was offset by the parish’s sale of the West 40th Street property to the Republican Club three months earlier.

As was common, while construction continued on the building, services were initially held in the only completed section–the basement. On January 11, 1902, The Evening Post remarked, “St. Ignatius Episcopal Church has begun services in the basement of its new church edifice…The church itself will be ready for occupancy at Advent, 1902.”

“When St. Ignatius’s Episcopal Church is completed…the West End-ave. block between Eighty-sixth and Eighty-seventh sts. will present a unique appearance. It will be wholly covered by two churches, both of them as distinct in architecture as are to be found in America.”

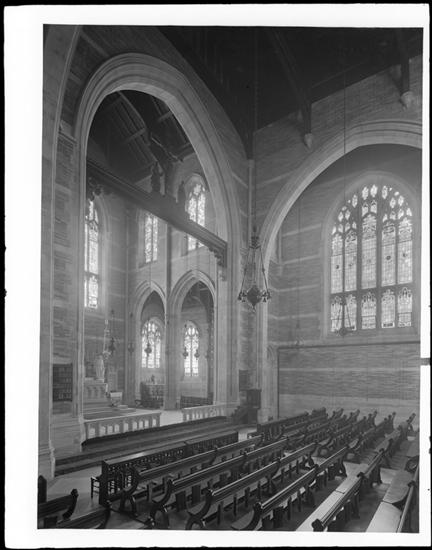

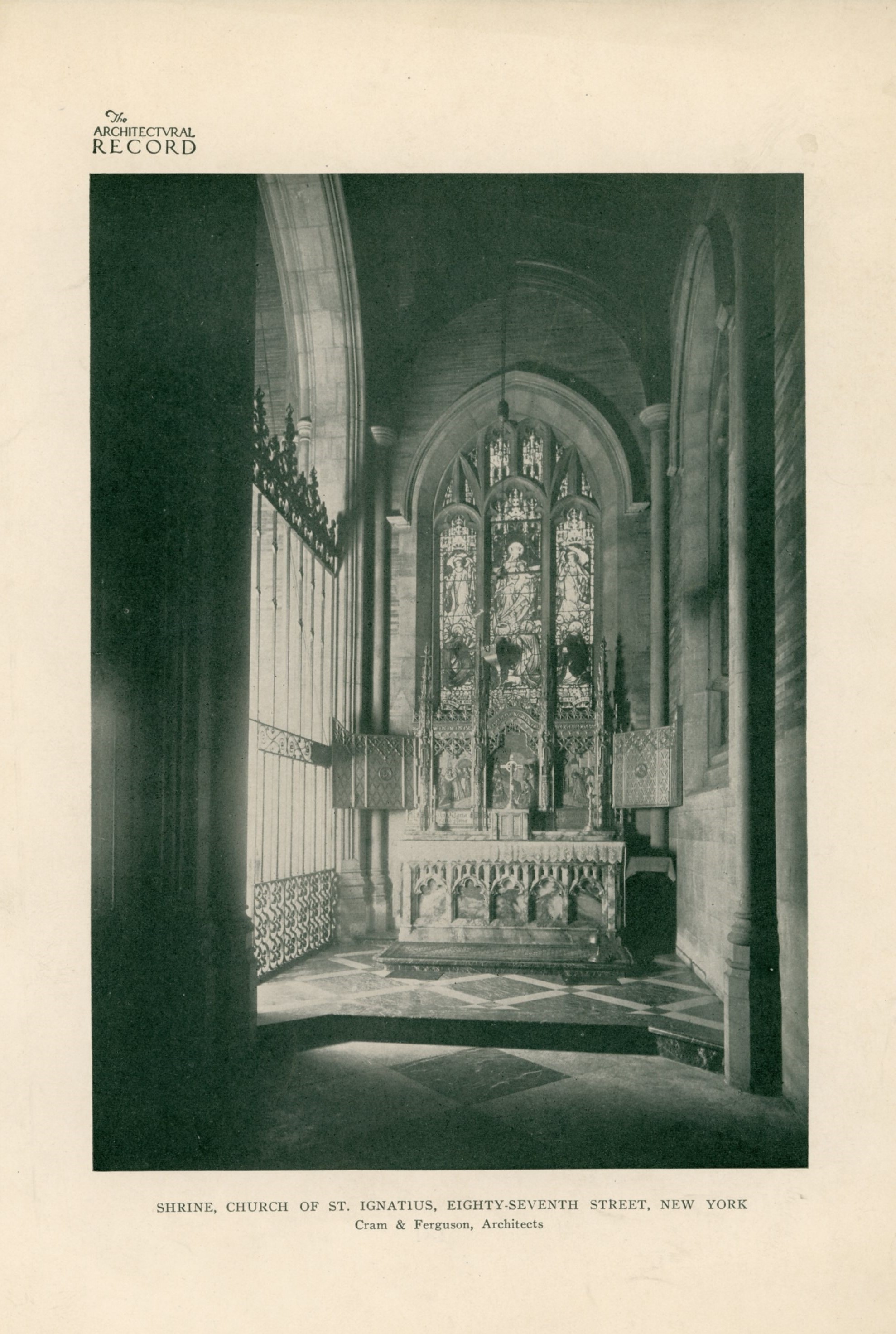

The first services in the completed sanctuary were held on October 19, 1902. The New-York Tribune described the granite-clad exterior as “severely plain.” The interior was finished in light-colored Roman brick and trimmed in stone. “The chancel is beautifully furnished,” said the article, “and is divided from the nave by an elaborate rood beam. The building is cruciform but with a short chancel and shallow transepts.”

The sale of the old building did not completely pay for the new structure and its furnishings. It would be several years before the finishing touches were completed inside. Female church members routinely helped fundraising efforts with what were known as fairs.

On February 2, 1903, the New-York Tribune reported, “Things dainty and serviceable, necessary and beautiful to look upon–all sorts of things, in fact, from the most delicate handmade lingerie to the simple cap and apron of the maid of all work–are daily on view (and on sale) in the guild room of the new St. Ignatius Protestant Episcopal Church…The members of the guild are working very hard to complete some details of church furnishing, which the new edifice still needs and their efforts have made a visit to the guild room well worth while.”

Father Arthur Ritchie had been rector since 1884. When well-to-do parishioners died, they often left bequests to their churches or, in some instances, to their parish priests. And, when the widow Charlotte M. Hoyt died in December 1902, she left a surprising legacy to Father Ritchie. Mrs. Hoyt was what might be deemed a “cat lady” today.

On January 16, 1903, The Sun reported, “By the will, Mr. Ritchie is to receive $5 a week as compensation for caring for the collection of cats that Mrs. Hoyt left, providing of course that he cares for the cats.” (The compensation would equal about $150 per week today.) Ritchie’s Christian compassion did not extend to a brood of felines, however. His response was quick and decisive. “I think I would make myself ridiculous taking charge of a lot of cats, and I don’t propose to do it. If the cats are sent to me I will turn them over to the animal society.”

Little by little the interior took shape. Charles Frederick Zabriskie, the senior warden, had long been one of the parish’s most generous supporters. He had donated a marble statue of the Blessed Virgin to the old structure in memory of his father, which now stood at the left of the altar in the new church. In 1904, he donated a second marble statue, this one of St. Ignatius, to stand on the right side.

A notable step towards completion came the following year. On October 7, 1905, The Evening Post reported, “One of the largest chancel windows ever placed in a New York church has just been set in St. Ignatius Episcopal Church, West End Avenue and Eighty-seventh Street. The window covers more than two hundred square feet. Another window, in process of making, is soon to be set in the south transept of the church.” The vast window had been executed by John Hardman & Co. of Birmingham, England.

James Remington Fairlamb had been organist and choirmaster of St. Ignatius Church since 1901. Known internationally as an organist and composer, he had also served as the United States Consul at Zurich. Born in 1838, Fairlamb had studied music in Europe, and had been decorated by the King of Wurtemberg with a “Great gold medal of art and science.”

Assisting Fairlamb was organist Charles Baier, who lived in Jersey City, New Jersey. Parishioners were no doubt concerned when he left his home on Monday, January 7, 1907 and did not return. Friends and family were only partially relieved when he walked back in the door four days later. The Sun reported, “He had suffered from mental trouble as the result of worry over the thought that his sister would be obliged to undergo an operation.” The family refused to give a statement “as to Mr. Baier’s wanderings,” but did say the organist “is now under the care of a physician.”

As Arthur Ritchie’s 25th anniversary of service to St. Ignatius Church neared in 1909, the New York Herald reported, “nearly a week’s celebration is planned.” Normally on such an occasion, the priest would receive a large cash gift from the congregation. Ritchie, however, declined the gesture before it could be made. The New York Herald said on April 17, “He suggested that the money be used toward the mortgage,” and noted, “It is expected that $25,000 will be given.” The rector had generously declined the equivalent of around a third of a million in today’s dollars.

Ritchie stepped down as rector on May 1, 1913, due to ill health. He became chaplain of the Bell Home in Nyack, New York, a complex where “folks who had little of this world’s goods” could find retreat. He died there on July 9, 1921, at the age of 72 and his funeral was held in St. Ignatius Church on July 13.

Perhaps the public’s first hint of the congregation’s artistic interests came in the 1920’s. On June 4, 1927, The Billboard announced, “The group of young people at St. Ignatius Church known as the St. Ignatius Players, gave a group of playlets at the Parish Hall, 552 West End Avenue, New York City on the evening of Tuesday, May 31.” The article said, “There was music between the acts, and afterward the audience held an old-fashioned strawberry festival, for which certain conservatives of the parish have been clamoring for years.”

“One of the largest chancel windows ever placed in a New York church has just been set in St. Ignatius Episcopal Church, West End Avenue and Eighty-seventh Street…”

The tradition of art continued. On March 15, 1976, organist Frederick O. Grimes and harpsichordist Harold Chaney gave a recital, for instance. On November 19, 1982, The New York Times reported that “the Wond’rous Machine” would be singing that weekend, and in October 1986 the newspaper reported, “The Stellar Consort plans a performance of madrigals, lute songs and instrumental works” here.

St. Ignatius Church was, of course, the venue of socially important weddings and funerals over the decades. One of the most notable ceremonies, however, was the funeral of Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Murray Kempton on May 8, 1997. A regular worshiper at St. Ignatius, if he happened to miss a Sunday service, according to warden Antonio Ramirez, “he’d tool around on his bicycle midweek to drop his offering in the mail slot.”

Kempton was famous, having worked for Newsday for 15 years and The New York Post for years before that. More than 400 people squeezed into the church for his funeral. But Kempton had seen to it that there would be no great platitudes. Clyde Haberman of The New York Times wrote, “Mr. Kempton wrote unshakable instructions on how his funeral should proceed. There were to be no eulogies, he decreed. No coffin on display. No trawling through his decades as a newspaper columnist and conscience of American journalism. No observations about how we shall never see the likes of him again, a point that had been obvious anyway for a good five decades.”

Instead, the funeral followed the ritual of the Church of England’s 1559 version of the Book of Common Prayer. Haberman wrote, “Yesterday, every nook and cranny of the church was filled, some by crooks and nannies.” At the end of the service, the church bell tolled 79 times, once for every year of Kempton’s life. Father Hitchcock said the gesture was “outside the realm of the instructions,” but he hoped Kempton would not have minded too much.

Charles Coolidge Haight’s dignified St. Ignatius of Antioch Church continues to be an odd bedfellow with its block-mate to the south, struggling hard to earn the attention it deserves, hogged by the exotic structure next door.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com