Society for Ethical Culture

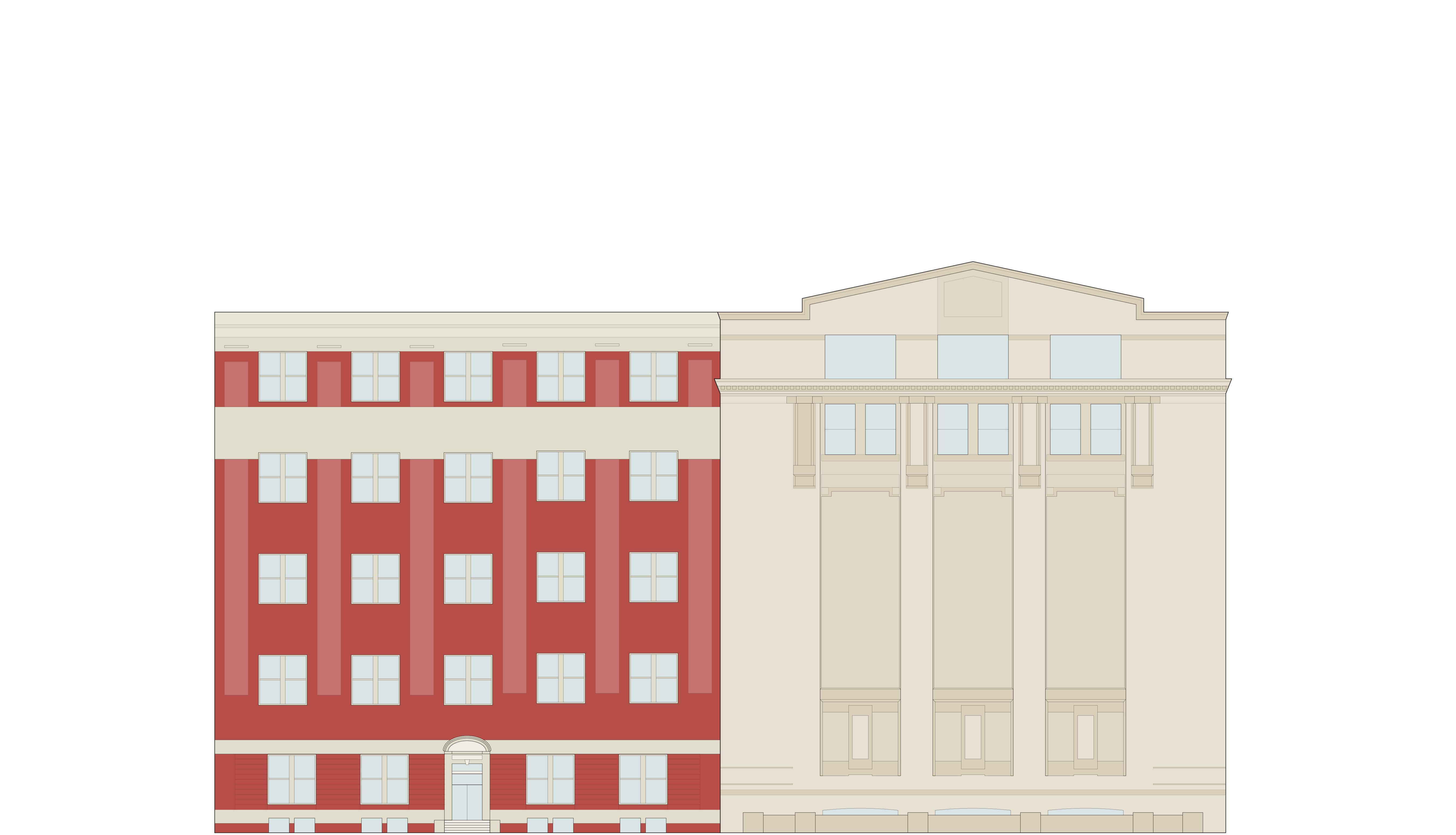

33 Central Park West aka 2 West 64th Street

by Tom Miller

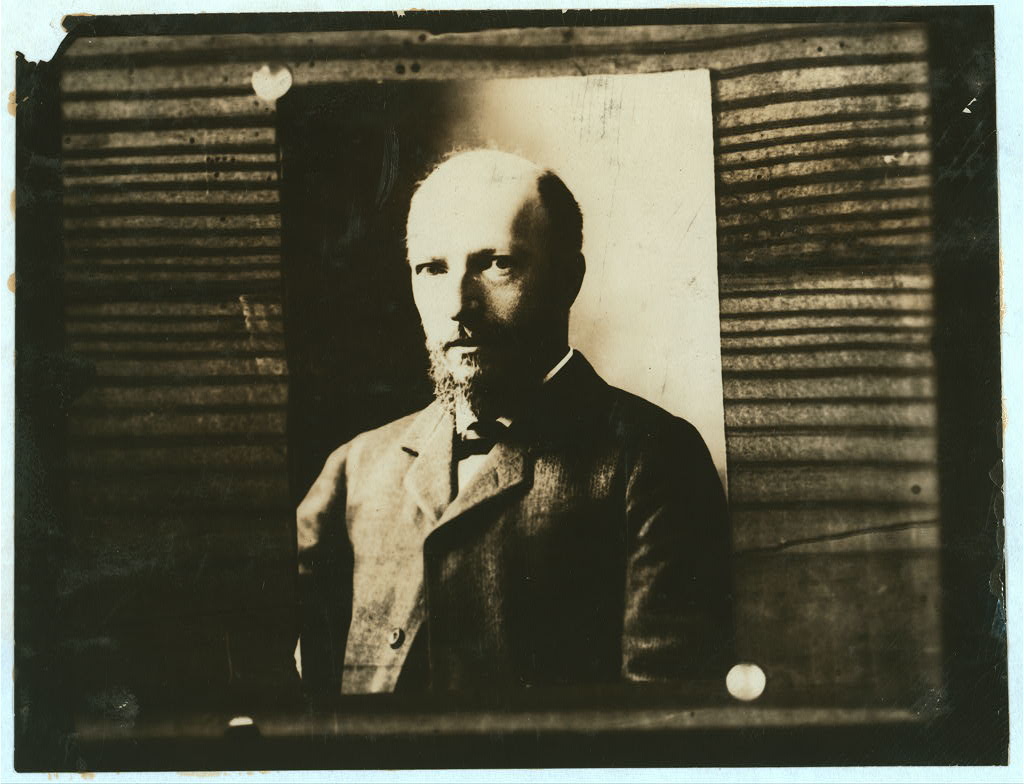

The Ethical Culture movement sprang from the mind of 25-year-old Felix Adler in 1876. It was a brash, unexpected, and brave undertaking for the son of the rabbi of New York City’s most prestigious synagogue, Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue. The Social Reform movement in America had already gained momentum, but the German-born Adler’s vision went further. His Ethical Culture’s focus on enhancing ethical standards would logically include human rights, racial and sexual equality, humanitarianism, housing, political principles, and religion.

Adler’s Society for Ethical Culture was incorporated on February 21, 1877. The society plunged headlong into the problems of those in need, creating a visiting nurse service and organizing the first free kindergarten in the United States. Quickly other programs followed—the Workingmen’s School in 1880 (which became the Ethical Culture School in 1895), the Mothers’ Society to Study Child Nature, and in 1889, the Visiting and Teaching Guild for Cripple Children. Similar programs were added, contributing to the Society’s esteem within the community.

But there was one aspect of the Society which made staid citizens uneasy. The religious services of the Society were “non-theistic.” The members did not recognize the traditional religions and its marriage ceremonies treated the bride and groom as equals. The word “obey” was not included in the short ceremony. Dr. John Lovejoy Elliott would later explain “Morality is supreme, we believe, and I think that everybody who is decent is an ethical culturist.”

As might be expected, as the Society grew, differences of opinion on its management arose. On March 3, 1909, the New-York Tribune noted, “Born out of a rebellion against the orthodox religious forms, the society now finds itself in the curious position of being divided into ‘high church’ and ‘low church’ parties.”

The day before, member Percival Chubb addressed the women’s conference of the Society. He expressed his concern that the Society was “cold” and “too colorless to hold young women.” He suggested that all it would take to make young female members abandon the Society was to “get their heads inside an Episcopal church, or any other that has a little ‘color’ in its worship, and ‘off they go.’”

Already, plans have been made for a new, permanent headquarters for the Society for Ethical Culture on Central Park West and the corner of 63rd Street. Chubb offered his views of what it should include. “We are going to have stained glass windows and frescoes and an organ. Why should we not have more and give these young people what they want? They want a beautiful celebration of marriage, a beautiful rite of admission, a beautiful ceremony for the naming of children.”

He expressed his concern that the Society was “cold” and “too colorless to hold young women.”

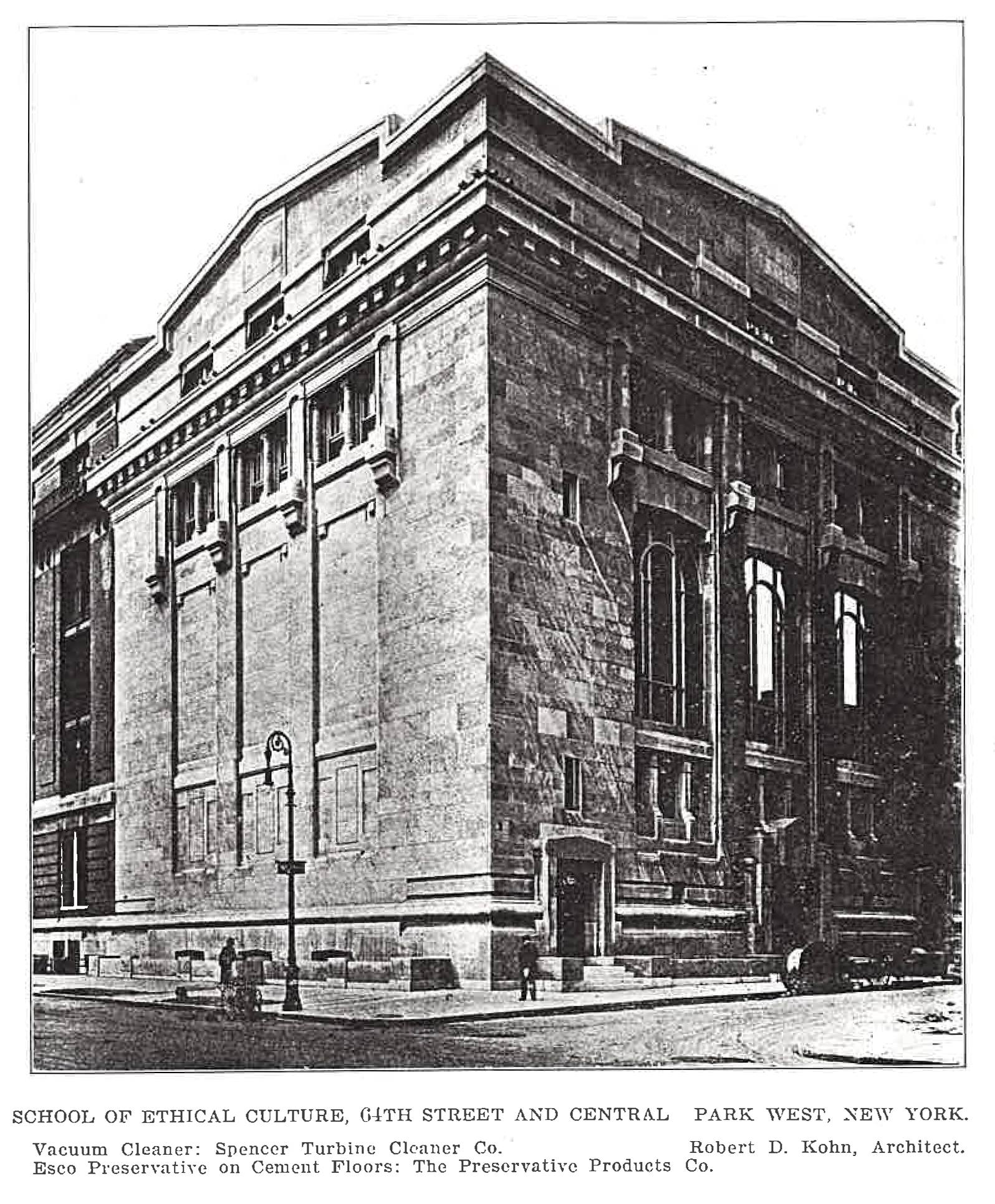

Another member, Robert D. Kohn, was not quite as enthusiastic as Chubb. The respected architect had recently completed the New York Evening Post Building and the Spero Building, both striking examples of Art Nouveau architecture. Now, on June 23, 1909, he filed plans for a $300,000 “four-story and basement meeting house and Sunday school” for the Society for Ethical Culture.

If Percival Chubb wanted the “color” of the Episcopal Church, he was sorely disappointed. Instead, Kohn produced a dignified and somber edifice, the style of which the Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide said could not “be ‘tagged,” in the sense of having borrowed its elegance of manner from some accepted style of architecture.”

Dedicated with “appropriate ceremonies” in October 1910, the building was widely praised. The Guide, on October 29, said Kohn “has received wide commendation for the graceful originality and the artistic honesty of his conception.” A letter to the editor of the Evening Post said, “at a time when buildings are springing up on every hand the most successful of which claim our favor by some derived nobility of style, it is worth while to note the birth of a building conceived in a totally different spirit.” The writer summed up his critique, saying, “Conviction is in every big line of this composition; an air of necessity, of massive simplicity pervades the whole.”

“Massive simplicity” perfectly defined Kohn’s building. The Record and Guide noted, “The exterior walls are built of massive blocks of limestone, hand cut with tooth chisels.” High above street level Kohn included tall niches on heavy brackets, nearly identical to those in his New York Post Building, intended to house statues. There was no grand portico, no classical columns; simply a sturdy block defined by geometry and openings.

Typical of the Society’s focus on equality, the few sculptural details were done by women. Above the entrance was a bas relief executed by the architect’s wife, Estelle Rumbold Kohn, of figures in “an attitude of reverent light.” Four smaller figures of torch bearers decorated the side entrances.

The New York Times was moved. “The severe plain wall is eloquent in its protest against the breathless rush and hustle of the modern city; it beckons to the hastening, sordid throng: ‘Tarry a while; there is in life more than stocks and shekels and vain show.’”

Far afield from Episcopalian abundance, the auditorium was relatively severe. Stained glass windows on the north wall provided color and ornament; otherwise the vaulted ceiling, the oaken pews arranged in a fan-shape on the inclined floor, and the simple stage, while relatively understated, created an inspiring space. The Times explained “The new Meeting House is designed for service and for comfort; it is not a Vanity Fair, neither is it a prison of the spirit.”

Felix Adler’s views on education and religion would continue to raise eyebrows among traditionalists. Not long before the completion of the 64th Street building, he explained to a New York Times reporter, “Moral training is necessary for everyone; religious training is another matter. Not every one is born with a religious nature; there can be unreligious persons just as there are unmusical persons.”

He continued, “Very great harm is done by trying to force religion on people who are not by nature religious…Much of the tragedy of history has arisen from no other cause than insistence in forcing religion on persons irreligious by temperament and their consequent misconception of it.”

Three weeks after the building’s dedication, Adler’s views shocked some–perhaps even some of the Society. While speaking in the auditorium on “Christianity and Socialism” on November 20, he criticized Socialism for insisting that all men were equal. Although he explained “I do not object to equal shares. I would not mind wearing the same sort of clothes as a workingman, eating the same sort of food, living in the same kind of a house. That is not the reason why I object to expressing brotherhood as equality of satisfaction of desires.”

He gave an example. “I do not think of the drunken man in the gutter as like me. He is like and yet he is very unlike. I don’t like too close contact—I would prefer a certain distance between myself and my fellowman, like that which separates the planets, each revolving about the sun and governed by it, yet each in its own orbit.”

The Society’s interest in all religions and adherence to none was exemplified by the series of services headed by associate leader Alfred W. Martin beginning on January 8, 1911. His topics included “Introducing the Discovery of the Sacred of Sacred Books of the East and Its Ethical Effects,” “Gotama, the Buddha, and the Path to Salvation,” “Zoraster, the Prophet of Industry” and “Confucius, Lao-Tze and the Problem of Good Government.”

It was the marriage ceremonies that most often drew press attention. On October 21, 1912 Hilda Matzner married Louis O. Schwartz. The headline in The Sun ignored the names of the couple; rather it focused on the non-traditional ceremony. “No Ring and No ‘Obey’ Will Bind These Two—No Mention of Love in Their Ethical Culture Society Marriage.”

When pressed by a reporter to explain why the Society dropped the phrase “to love and obey” from the ceremony, Dr. John Lovejoy Elliott replied, “As far as marriage goes, we believe in common with all other good thinkers, that man dedicates himself to the idea that the woman’s welfare should be placed by him before his own; and the woman dedicates herself to the idea that the man’s welfare should be placed before her own. There is nothing mysterious about the ceremony and nothing startling.”

The Sun’s report included a sub-headline that read “Ethical Culture Ceremony Exacts No Promise to Obey Husband.”

Apparently the explanation was not sufficient for The Sun. When Maude R. Ingersoll was married to Wallace McLean Probasco two months later, on December 30, 1912, The Sun’s report included a sub-headline that read “Ethical Culture Ceremony Exacts No Promise to Obey Husband.” Not overlooking the fact that Maude’s deceased father was “the agnostic,” the newspaper added, “Miss Ingersoll has long been a member of the cult.”

The Society’s concerns for social welfare included Felix Adler’s seat on the first Executive Committee of the National Urban League in 1910. He was, incidentally, also Professor of Political and Society Ethics at Columbia since 1902. (Adler’s professorship at Cornell University had earlier been removed because of his “dangerous views.”)

Emblematic of the wide-range of events in the building was A Better Industrial Relations Exhibit held from April 18 to 25, 1914. Iron Age described it saying, “It will show the devices in modern business which tend to make more harmonious the relations between employer and employee, and to better the conditions of employment.” And, in 1915 the building hosted a meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which the Society had been instrumental in founding.

The auditorium was repeatedly the scene of lectures and discussions; many of them controversial. Harriet Stanton Blatch reprimanded American women on Monday afternoon, March 25, 1918. She said the women of the U.S. were lagging in war work and “must wake up.” The New-York Tribune reported she “dropped this bomb into the meeting of the Society for Ethical Culture…when she declared that American women were not doing nearly enough to help the war, and that the time would come when they would be called upon to bend their backs to men’s labors, even as the women of Europe have done.”

She pointed out that 60,000 German women were making military uniforms and that French women and girls were working the farms. Blatch reprimanded, “We are too extravagant…We are too fond of ‘the way mother used to do.’ Imagine fifty women standing over fifty stoves, boiling fifty little pots of potatoes! Women, wake up. That sort of thing won’t do. We must adopt the time and labor saving devices that science has put in our hands. Mother’s way won’t do for the terribly poor world we have got to reconstruct after the war.”

The auditorium was the scene of marriages and funerals over the decades, but perhaps none was so noteworthy as that of Felix Adler himself, who died at the age of 81 in April 1933. The funeral was held on April 27.

Felix Adler’s death came at a time of great political upheaval in Europe. A year later, on Saturday, December 8, 1934, that climate was reflected in the topic of Dr. Hans Kohn, “Communism, Fascism and Europe.”

As Central Park West and 64th Street changed around it, the Society for Ethical Culture’s building did not. In 2004, architect Marc Holmquist and interior design firm Drake Design Associates completed a significant renovation of the auditorium. The exterior, as well as the Society’s goals, remain steadfastly unchanged save for redundant signage. Its website declares, “We embrace the diversity of our city and invite all to join us in celebrating life’s joys, supporting one another through life’s crises, and working together to make the world a better place.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Return to Central Park West

Landmarks Timeline

Return to Spirit of the City

Building Database

Designation Report

Be a part of history!

Stay local to support the nonprofit currently at 33 Central Park West, aka 2 West 64th Street: