New York Buddhist Church

331-332 Riverside Drive

by Megan Fitzpatrick

Reverend Hozen Seki, priest and founder of the New York Buddhist Church, came to the United States from Japan in 1930. Seki followed his father’s example and became a minister in the Jodo Shinshu school of Buddhism, and was involved in and helped found temples in New York, California, and Arizona. A blend of both Eastern and Western influences can best describe the practice of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism in America, as the Japanese American Buddhists gathered in ‘churches’ as opposed to the typical ‘temples.’ This was largely an attempt on the part of Japanese immigrants to make their faith seem less foreign and to assimilate into America at a time when there was great public skepticism and racism towards Asian immigrants, particularly after WWII.

Rev. Seki came to New York in 1938 and established the first New York Buddhist Church in the city. Rev. His journey to New York was by air but unconventionally in an open-cockpit plane with a Japanese pilot, in which they made several stops to refuel.

Seki lived at 171 West 94th Street, with his wife Satomi and two children, above the Hondo, or main hall, of the New York Buddhist Church that operated on the first floor. The Japanese Buddhist community in the city raised funds to purchase the dwelling, for $10,000, to set up a permanent place to hold services.

Almost two years after the family moved to New York to establish their new lives and a new church, Rev. Seki was arrested and taken to Ellis Island by two FBI agents. From there, he was moved to internment camps on the West Coast, as was the fate of many Japanese Americans living on the West Coast after the U.S. announced they were at war with Japan. Despite living in New York, Rev. Seki was subject to internment as U.S. officials regarded Japanese religious leaders as suspicious. He spent most of his internment detained at the Kooskia Internment Camp in Idaho.

While Rev. Seki was interned, his wife Satomi and other ministers kept the church going at West 94th Street. Since Rev. Seki was interned so soon after establishing the church, his family and Japanese American ‘resettlers’ (‘loyal’ Japanese Americans moved out of internment camps) in the city and Japanese American soldiers on leave, helped to build the congregation. The church provided accommodations and services for relocated persons who were Buddhist and those who suffered severe hardships during the war.

Rev. Seki was released in January 1946, following the surrender of Japan a few months prior, and soon after the church began to thrive and grow. A Sunday school was established as well as additional classes and activities that would encourage not only the Japanese diaspora to engage positively with Japanese culture but also the wider community in the city, at a time when many Americans still harbored bad feelings toward the Japanese.

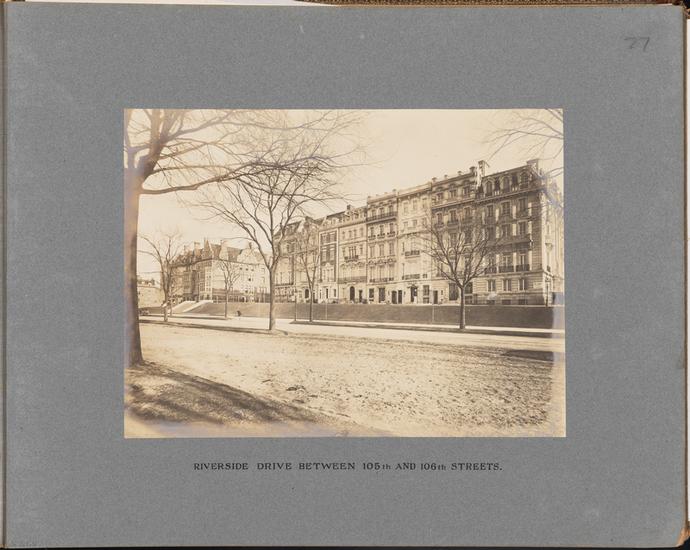

By 1955, the Buddhist Church had filed plans to develop an empty lot on Riverside Drive between 105th and 106th Streets. There were many reasons behind this move. As the Church was growing its membership, and its outreach into the wider community, a plan to develop an academy that would hold more classes came to fruition. They wanted to expand so they bought a 4-story building and its adjoining garden lot to develop their academy.

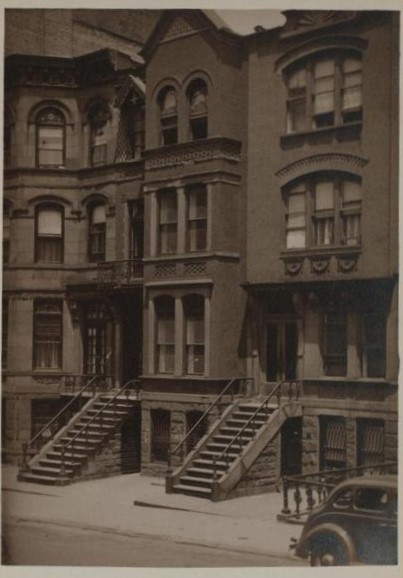

It can also be argued that the church leaders heard wind of plans to redevelop the land on which their original sanctuary stood. 171 West 94th Street, a rowhouse built in 1885 by prominent west side developers Squier & Whipple and architect E. C. Smith was demolished sometime after 1959. That year, a sweep of houses between Central Park West and Amsterdam Avenue from West 87th and 97th Streets were slated to be demolished as part of the “West Side Urban Renewal Area.” The site where the rowhouse and church would have stood is now a park and playground.

Despite living in New York, Rev. Seki was subject to internment as U.S officials regarded Japanese religious leaders as suspicious.

Plans to develop a Buddhist Academy in connection with the church were in motion for a long time. In 1948, on the 10th anniversary of its establishment, the Church announced its plan to open the American Buddhist Academy. In January 1955, it was reported in the New York Times that both 331 and 332 Riverside Drive were sold by Fred. H. Hill to the “American Buddhist Academy” (New York Times, Jan. 18, 1955).

The Academy would operate from 331 Riverside Drive while a new chapel would be built at 332 Riverside Drive. The firm of Janes & Leo built four mansions in 1902, all very similar in design from 330-333 Riverside Drive. The brick and limestone facades were typical Beaux-Arts designs with French windows at the parlor level and pronounced cornices. They were all built by renowned Upper West Side developer, Joseph A. Farley and cost a hefty $230,000 each.

At the new location, the Academy had dormitories and a library for students and held lectures promoting the teachings of Buddhism. As the Academy grew, it began offering courses for the general public on Japanese culture including language, literature, art, and music.

Rev. Egen I. Yoshikami was an associate minister of the Buddhist Church and taught many of the lectures at the Academy. Ordained in Kyoto, Rev. Yoshikami also taught Japanese culture and language at City College in the 1950s. His wife, Mrs Yoshikami, was also a minister at the Church and the first woman to be ordained a Buddhist minister in Hawaii, where the couple lived before moving to New York.

331 Riverside Drive is a sizable building originally built with 26 rooms, perfect for a small school. The rowhouse has an elegant and equal parts scandalous history. In 1918, the dwelling was sold to a “woman client” with an evasive description. The client was Marion Davies, the 21-year-old mistress of media mogul, William Randolph Hearst.

Hearst lived with his family conveniently nearby on Riverside Drive and 86th Street. Hearst’s son described him as “a sort of Stage Door Johnny” and he was captivated by the then 18-year-old stage girl. Her career catapulted with the help of Hearst-owned media singing her praises. Davies made most of her movies while living at 331 Riverside Drive and during her 30-year affair with Hearst.

Hearst spent 1 million dollars, close to 17 million dollars today, remodeling her house, including a library “with wood paneling and calf-bound rare editions” even though apparently Davies was not much of a bookworm. Davies’ mother, two sisters, and a crew of servants moved into the house. Hearst even bought the neighboring 332 Riverside Drive, before it was demolished, for her father Bernard. The author of ‘Gentlemen Prefer Blondes’, a satirical novel about a young girl with Hollywood ambitions, Anita Loos, had dinner with Davies in her mansion on Riverside Drive.

After the scandal of their affair was released to the public, Davies fled New York and Hearst bought her a house in Beverly Hills. 331 and 332 were sold to the neighbors, the Jephsons, and 332 was sold and turned into a multi-family apartment but ultimately demolished sometime in the late 1930s (Wakin, 2019, pp.50-56). It was then turned into a garden with a garage entrance by the owners of 331.

By 1963, the Church had fully moved into its newly constructed annex in the lot next to the Academy. In 1955, the firm of Kelly & Gruzen began constructing a 3-story glass and metal “chapel” for the church in that spot.

Many visitors to the church will notice a bronze statue of a Japanese Buddhist monk standing outside the entrance. The statue depicting the Buddhist monk Shinran Shonin, originally located in Hiroshima, survived the impact of the Atomic blast and was later transported to New York in 1955. Mr. Seiichi Hirose, a metal works industrialist, who became a devout Jodo Shinshu Buddhist following the untimely death of his child, cast six identical bronze statues of Shinran in travel attire in 1937. They were each around 15 feet tall and were placed in various cities in Japan including Hirose’s home of Kuwana in the Mie prefecture and Osaka, Tokyo, Kyoto, and Hiroshima.

During World War II, three of the six statues were destroyed and the metal was used for the war effort, however, the statue located in Hiroshima Park, which overlooked the city, survived. It survived the full blast from the Atomic bomb that hit the center of the city, about one mile away from Shinran. You can see some red scorch marks today on the statue from the blast.

Shinran’s journey to New York began towards the end of 1954. Mr. Hirose donated his artwork to the church, hoping its presence just a few blocks from where the bomb was developed at Columbia University, would awaken inspiration for peace and tranquility in the world. The Church made plans to have the statue sent over from Japan. On January 23, 1955, Rev. Seki received a letter from Mr. Hirose, it read:

“As spring arrives, I would like to say it is my great pleasure to make your acquaintance. I have read your letter of January 12. When I received it, before I opened it I placed it on my Butsu-don as a kind of offering. It was only after that, that I proceeded to open the envelope most respectfully. Regarding the plans you have laid down for the ceremony to be conducted for the Statue, let me say that I am most impressed by them and have nothing but gratitude to express. It has been my long cherished desire to follow through on my plan to have the Statue of the Shonin cross over to America”

The work to dismantle the statue began in April 1955 and a huge closing ceremony was performed before it departed on the cargo ship the Kochu Maru headed for New York where it would live in the garden of the Buddhist Academy and then in front of the new chapel after it was fully constructed. Hirose and Rev. Seki hoped the statue’s relocation to New York, a place that played a large role in the development of the Atomic bomb, would caution against any future ‘Hiroshimas’.

At the dedication ceremony on September 11, 1955, Buddhist philosopher D. T. Suzuki gave the keynote address. In it he stated:

“The present state of things as we are facing everywhere politically, economically, morally, intellectually, and spiritually is no doubt the result of our past thoughts and deeds we have committed as human beings through the whole length of history, how many years we cannot count, through eons of existence, not only individually but collectively… we are, every one of us, responsible for the present world-situation filled with awesome forebodings.”

The statue depicting the Buddhist monk Shinran Shonin, originally located in Hiroshima, survived the impact of the Atomic blast and was later transported to New York in 1955.

Rev. Hozen Seki retired from the leadership of the Church in 1987 and died in 1991 in his home in Lahaina on Maui. Followers of Rev. Seki said he was a progressive and “a renegade” who revolutionized the way Japanese Americans and non-Japanese Americans practiced Buddhism.

The Church continues to operate out of Riverside Drive, holding numerous events and festivals throughout the year. The American Buddhist Academy is now the American Buddhist Study Center, with Rev. Seki’s daughter as its president. The ABSC is one of a few Buddhist publishing houses in the USA. The facade of 332 Riverside Drive has changed forms many times over the years but now displays a quiet strength with the statue of Shinran Shonin watching over the Hudson River.

SOURCES

New York Times, January 18, 1955

Barnard Bulletin, October 24, 1957

New York Times, July 25, 1991

American Buddhist Study Center, “About”, 2024.

CBrooks, “Odd coincidence at the New York Buddhist Church”, Asian American History in NYC, Oct. 17, 2013. Accessed 3.29.2024.

The City of New York, “West Side Urban Renewal Area Report”, 1959.

Digital Museum of the History of Japanese in NY, “The New York Buddhist Church”, Mar. 20, 2021.

Hoshina Seki, “Hoshina Seki Describes Path as a Trans Woman”, Buddhist Churches of America, 2020.

Michael Haederle, “Profile: The New York Buddhist Church”, Lion’s Roar, 2014. Accessed 3.29.2024.

Midwest Buddhist Temple, “Rededication of Shinran Shonin Statue in New York City”. Accessed 7.27.2023.

Wakin, Danial, J., (2019) “The Man With The Sawed-Off Leg”, Arcade Publishing, New York.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Preservation and Research Director at LANDMARK WEST!