By Claudie Benjamin

By Claudie Benjamin

Latin Music and its infusion into early Jazz arrived in New York City by design rather than by chance. Several well-documented migrations of Puerto Ricans to the Upper West Side’s San Juan Hill, and other blocks mainly occurred after WWII, in the late 40s, 50s, and early 60s.

However, Latin music and its part in introducing early jazz to New York City and beyond came much earlier – in the early 1900s.

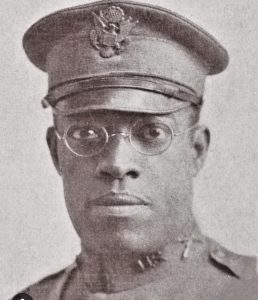

The origin of this exciting and enduring influence is closely allied to the brilliant Black bandleader James R. Europe. Born in Mobile, Alabama, he was not Puerto Rican and did not speak Spanish. Europe had moved to NYC in the early 1900s to build a career as a performer and composer. He was well trained. This was unusual for talented aspiring Black musicians at the time who were not usually, if ever, admitted to segregated music schools.

In addition to what seems like engaging in feverish music production, Europe was among other Black musicians who organized The Clef Club and later Tempo Club, which served as social clubs and booking agencies for Black performers who were generally turned away from non-Black organizations. The early activities of these clubs in and around San Juan Hill have been described as having likely occurred at the very popular, cosmopolitan Marshall Hotel (127-129 West 53rd Street) that drew a multiracial crowd. The hotel was located on West 53rd Street across from the building where the Clef Club later took up quarters. Among the most acclaimed of the many performances of music and dance booked by Europe and the Clef Club was the sponsorship of a 100-piece symphony orchestra for the performance of music by Black composers at the White establishment venue Carnegie Hall on West 57th Street.

When Europe’s career was developing, conservative musical audiences were timid in expressing any appreciation of Latin music.

When Europe’s career was developing, conservative musical audiences were timid in expressing any appreciation of Latin music.

The syncopated rhythms and bold sensuality of its dance moves became known in the early 20th Century; however, they were not considered socially appropriate until the legendary dance team Vernon and Irene Castle incorporated the elements into their wildly popular performances. The couple learned about this music from “Jimmy” Europe, whom they had met at a private party in 1913, through his role as a band leader of his Society Band that played for elite events on Long Island. The Castles hired him and he served through 1915 as their music director. An anecdote reflective of the progressive stance of the Castles (who were and their resistance of racial prejudice against fellow performers appears in Syncopated Times: “In January of 1914 the Castles landed an engagement at the Palace Theater (Broadway and 47th Street) and Hammersteins’ Victoria Theatre (42nd Street and Seventh Avenue) in New York City. These venues were considered the height of show business at the time. A problem arose when the segregated musician’s union objected to Europe’s Society Orchestra (who were African-American) performing in the orchestra pit with the regular White orchestra. The Castles insisted that Europe’s Orchestra accompany them and solved the racial impasse by having the band sit on-stage rather than in the orchestra pit. This was the first time that an African-American orchestra performed at the first-class New York Vaudeville theatres.”

After enlisting in the 15th Regiment of New York National Guard in 1916, Europe was asked to organize a National Guard regimental band…while this was certainly an honor, it was also a huge challenge. The musicians, as per military policy of the time, required units to be segregated. Europe’s approach to the problem was to turn to Puerto Rico. He had learned that band players held a respected position in the workforce and were also highly trained. Europe spent three days recruiting in Puerto Rico. Auditions were likely scheduled in advance of his arrival in Puerto Rico. During this quick visit, He recruited 18 members to his band.

The band, later known as the Hell Fighters, took off for France in 1917. Once there, this National Guard Unit joined the 365th, a segregated regiment of the French Army, and by an unanticipated set of circumstances, served in combat for 191 days. While in France they played for wounded soldiers at the American Red Cross Hospital in Paris, at the army camps and the French villages. The band members were acknowledged as heroes collectively and individually awarded The Croix de Guerre. On their return to NYC, they were honored as heroes in a parade from 5th Avenue to Harlem.

Soon after their return from France, an engagement of the band in Boston proved to be fateful. According to the New York Times, angered that Europe instructed him to pep up his playing, one of the drummers in the band followed him backstage, fatally stabbing the 38-year-old Europe in the neck.

Europe’s funeral held in Harlem, was attended by thousands. The former Puerto Rican Band members followed different paths. The most famous is the musician and composer Sgt. Raphael Hernandez, whose recordings include early jazz pieces, and whose music is known worldwide.