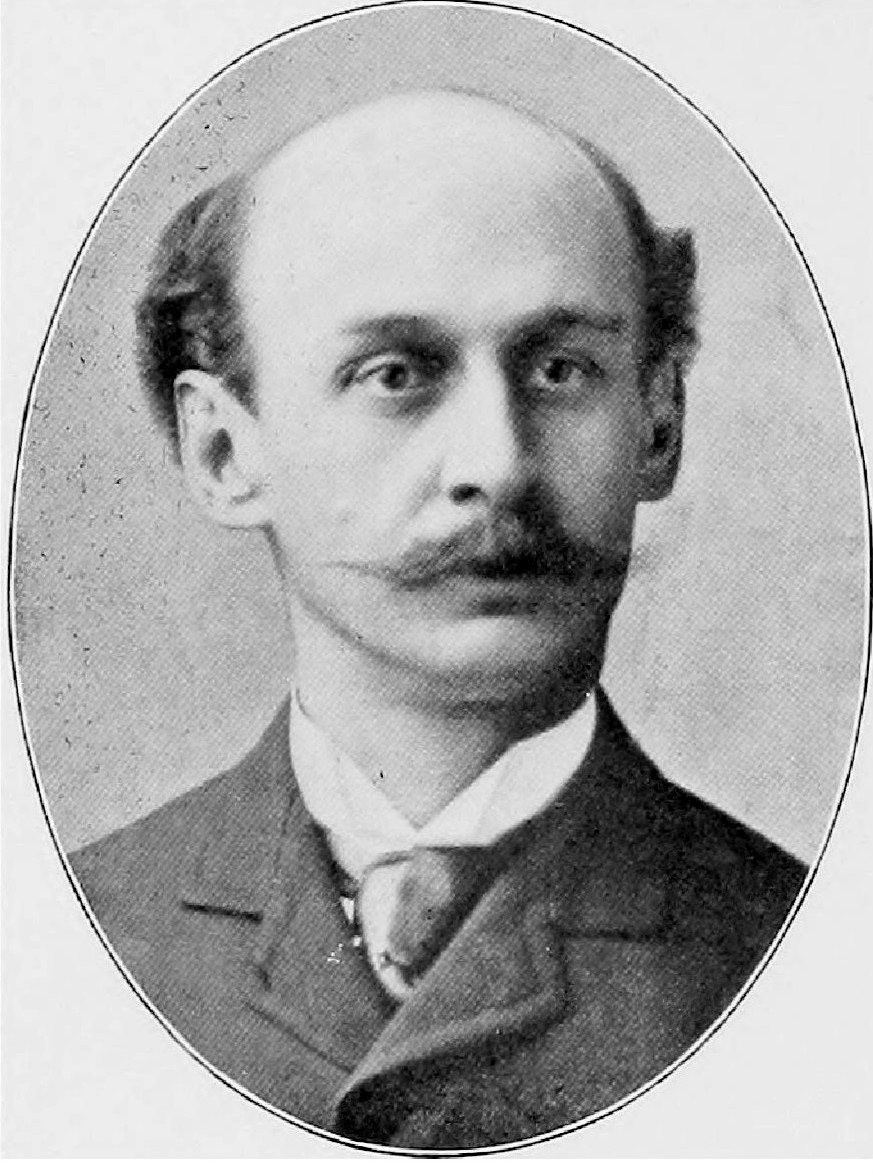

Henry Janeway Hardenbergh

Henry Janeway Hardenbergh (1847-1918)

Architect Henry J. Hardenbergh was born in 1847 in New Brunswick, New Jersey, into a family of Dutch lineage.[1] He was a student at the Hasbrouck Institute, a preparatory school in Jersey City that aimed to prepare young men in Jersey City to attend the most prestigious colleges and universities in the country and to enter public service.[2] He then went on to complete his architectural training from 1865-70 under Detlef Lienau, a Beaux-Arts trained architect. Hardenbergh started his own architectural practice in 1870 in New York and became one of NYC’s best-known and most respected architects. Hardenbergh designed many buildings in multiple styles over the course of his career. He designed buildings that were both picturesque and practical, taking inspiration from the German, Dutch, French and Italian Renaissance styles. In terms of use, Hardenbergh designed many types of buildings, including country homes, rowhouses, and office buildings. However, he is best known for his luxury hotels and apartment houses.[3] Hardenbergh appears to have mostly worked as a solo architect, but he did practice for a short time with John P. Hardenbergh Jr. and Adriance Hardenbergh, supposedly his brother and nephew.[4]

One of Hardenbergh’s early commissions was for a chapel, a library (demolished) and a geology building (reportedly still standing) for Rutgers College (New Brunswick, NJ) from 1871 to 1873. He received the commission, supposedly, through a set of family connections. Hardenbergh’s success started in 1880, when Edward S. Clark, head of Singer Sewing Machine Co. saw his Van Corlear (1879), an apartment block on West 55th Street (NYC) and commissioned him to build a set of housing developments for the three social classes between what is now called West 72nd and 73rd Streets and Eighth and Ninth Avenues. The commission resulted in a set of row houses (some were destroyed), lower-middle-class apartments, and the famous Dakota Apartments (1880-84, NYC Landmark, in the Upper West Side/Central Park West Historic District), all with a mixture of style in their facades, including German Renaissance and French Chateau.

In 1893, nearly ten years after the Dakota was completed, the Astor Estate hired Hardenbergh to design the opulent Waldorf Hotel (1893, destroyed 1931), and its equally famous addition, the Astoria Hotel (1896, destroyed 1931). Designed in the Edwardian Style, these two hotels made Hardenbergh even more famous, and established him as a master architect for Edwardian hotels. His other Edwardian hotels include the Martinique (1897, New York City), the Plaza (1907, New York City, interior altered), the Willard (1906, Washington, DC), the Copley Plaza (1912, Boston, MA), and the Windsor (1903, Montreal, Canada).[5]

The Van Corlear (1879), left; precursor of the Dakota (1880-84), right; these two buildings had the same architect (Hardenbergh) and developer (Edward Clark).

Part of what made Hardenbergh so successful in designing luxury hotels was his understanding of their functional nature. In 1902 he wrote a new set of standards for the planning and placement of bathrooms and kitchens, and also wrote formulas for adding elevator service.

Hardenbergh was also a member of multiple professional organizations over his lifetime. He was a founding member of the American Fine Arts Society and the NYC Municipal Art Society. He was elected a fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1877 after having joined the society in 1867. He was the president of the Architectural League of New York from 1901 to 1902 and he showed his work at many of the League’s annual exhibitions. Finally, he was an associate of the National Academy of Design from 1910. [6]

In regards to Hardenberg’s personal life, the information is scarce. He married Emily Irene Leeds Keene in 1893 but they did not have any children.[7] The 1900 census lists him as a widower. He split his time between living in New York and his home state of New Jersey, in a large town house that he had designed at 12 East 56th Street in New York City, and at 121 West 73rd Street in Jersey City. When World War I began, Hardenbergh was still working as an architect. The war led to a limited construction market, which put his career on pause. He died in New York City in 1918 at the age of 71, before he could resume his career.[8]

Bibliography

This post referenced information from the following LPC designation report:

Consolidated Edison Building: 4 Irving Place, Manhattan

Broderick, Mosette Glaser. “Hardenbergh, Henry Janeway.” In The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art. : Oxford University Press, 2011. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195335798.001.0001/acref-9780195335798-e-855.

Gray, Christopher. (2000, May 07). “An architect who left an indelible imprint.” New York Times. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/docview/431453258?accountid=10226

“Hasbrouck Institute 50 Crescent Avenue, between Crescent and Harrison Avenues Jersey City Heights.” Lincoln Park. Accessed June 07, 2018. https://www.njcu.edu/programs/jchistory/Pages/H_Pages/Hasbrouck_Institute.htm

Stone, May N. “Hardenbergh, Henry Janeway (1847-1918), architect.” American National Biography. Accessed June 07, 2018. http://www.anb.org.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-1700368;jsessionid=C7C159D9DDA333D3F6A39518F018A082

[1] Consolidated Edison Building: 4 Irving Place, Manhattan.

[2] Consolidated Edison Building: 4 Irving Place, Manhattan; “Hasbrouck Institute 50 Crescent Avenue, between Crescent and Harrison Avenues Jersey City Heights,” Lincoln Park, , accessed June 07, 2018.

[3] Consolidated Edison Building: 4 Irving Place, Manhattan.

[4] Christopher Gray. (2000, May 07). “An architect who left an indelible imprint.” New York Times.

[5] Mosette Glaser Broderick, The Grove Encycolpeadia of American Art (Oxford University Press, 2011), s.v. “Hardenbergh, Henry Janeway,” accessed June 7, 2018.

[6] May N. Stone, “Hardenbergh, Henry Janeway (1847-1918), architect.” American National Biography. Accessed June 7, 2018.

[7] May N. Stone, “Hardenbergh, Henry Janeway (1847-1918), architect.” American National Biography. Accessed June 7, 2018.

[8] Christopher Gray. (2000, May 07). “An architect who left an indelible imprint.” New York Times.