Rose Moligano Rudnitski today

When Vincent Calise came to New York around 1902, with his mother, sisters, Francesca and Nunzielle, and many fellow arrivals from the island of Ischia, a volcanic island near Capri, they settled near each other on West 67th Street, and Vincent eventually became the keeper of the statue the immigrants brought with them of Saint Restituta, patron saint of the town of Lacco Ameno. Although the neighborhood Catholic Church, St. Matthew’s was down the street, the very large statue resided in Vincent’s apartment in the building next to 236 West 67th Street, where most of the immigrants settled. The community held a traditional Italian saint’s feast festival on the block every May, as they did and still do in Lacco Ameno every year. At the age of five, Rose Moligano Rudnitski led the “angels” at the head of the Feast Day parade that was held annually on May 17 in San Juan Hill.

Numerous immigrants, including her maternal grandmother, Francesca Calise Burrello, and other relatives from Ischia lived in Rose’s building at 236 West 67th Street in San Juan Hill. Rose has good memories of life in the neighborhood. The feast (similar to the ongoing San Genaro feast held in the Village) was not only exciting, but it was also meaningful. “We had an Om Pa band, sausage and peppers, the street was closed for the occasion. For the most part, we were all poor but we helped each other. The sense of care was strong in the community.”

A vivid childhood memory that reflects on love as well as on poverty has to do with Rose’s favorite food – spinach. “My mother was making spinach for me in the double boiler. It exploded. No one was hurt. I was crying because I couldn’t have the spinach. My mother was crying because there wasn’t enough money to buy more. That’s how poor we were. But, there was so much love and care.”

Rose’s mother Giovanina (Jennie) Moligano, nee Burrello, left high school to help her parents with her two brothers who both had Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy. They were already living in San Juan Hill at 236 West 67th Street in apartment #1. After Rose’s parents married, they lived in the adjacent apartment, #2 on the same floor.

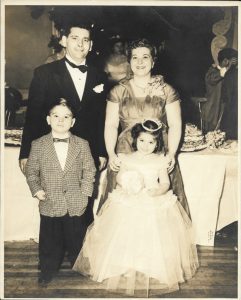

Young Rose at her cousin’s wedding in an angel dress

Both Rose’s mother, Jennie, and maternal grandmother, Francesca were seamstresses. They did piece work for the midtown garment industry. Piece work meant getting 15 cents for sewing a collar on a blouse and 25 cents for sleeves. The women sewed extremely fast in order to make a dollar. Eventually, her mother became a member of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and was chosen as shop steward. She mentored several generations of immigrant women, especially by checking their paychecks to assure that their pay reflected the amount of work they completed. It was a common practice for the shop owners to pay for fewer pieces than the women were owed. Jennie called it “shorting” their pay. The women loved Jennie, and she came home with small gifts from them that reflected the generations of immigrant garments workers she mentored: initially Italians and Jewish immigrants, then immigrants from Puerto Rico, and finally immigrant women from Asia who gifted her with many plastic Buddhas for her kindness in making sure that they were fairly paid.

Rose’s mother’s sewing skill helped stave off embarrassment for Rose. After the family moved to Long Island, to Bayville, a small town in the Locust Valley School district, money was lacking to buy clothing that was on a par with the other girls on the sports teams on which Rose played. She was embarrassed for not having designer clothing in the locker room like the other girls, but her mother came to the rescue. Jennie was sewing those designer labels in the sweatshop. She brought the patterns home and sewed the same clothing for Rose, affixing designer labels from the shop so she could fit in. True to Italian American tradition, Rose, who played shortstop on the girls’ softball team, was voted Most Valuable Player one year.

Rose’s father, Joseph, had only a fifth-grade education in Italy before he came to America with his mother and older sister. He was placed in 6th grade in P.S. 3 in Greenwich Village. (Decades later, Rose supervised student teachers in that school for the Teachers College programs.) Joseph did not know any English and was taunted by the other children for being a “WOP and dumb.” He quit school after two weeks in 6th grade and got a job as an ice man. He later worked as a taxi driver and a bartender. He discovered an aptitude for welding while in the US Army in WWII and eventually got a good job as a welder at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. This put the family in the middle class, but the stigma of the bullying in school and the inability of people to pronounce his last name, Molignano, caused him to change it to Moligano. His brother, Peter, on Horatio Street, did not change his, so there are two versions of that surname in the family.

Rose’s mother, Jennie, remained a piece worker and ILGWU shop steward until she retired. Rose’s maternal grandmother, Francesca continued to live in San Juan Hill for three more years until the building was condemned to build Lincoln Center. Rose’s parents, and brothers had moved to Long Island when Rose was five, because they were unhappy with the schools in the city. They felt that Rose needed better teaching than her older brother had experienced, so they moved to Bayville and built a house on a lot that Rose’s maternal grandparents gave them. “In the city, we had no books in the apartment – not even a Bible – but we did get the Daily News. Early on, although her father may have struggled with reading and read at about a 4th-grade level, he and Rose made it through the paper every day. “Something just clicked and I could read when I was four.” Later, her father was less supportive. Although she always excelled at school, he was not in favor of college for girls and disowned her after she went away to college on a full Regents scholarship.

Rose did not let paternal opposition stand in her way. She started her career as a music teacher in Norwich, NY, where she taught for 16 years. After requesting a sabbatical leave, which was initially denied, she went on to earn a 2nd master’s degree and an Education Degree from Columbia University’s Teacher’s College. To get the sabbatical, Rose had to go over the head of the school superintendent and she wrote to the board of education, which approved the sabbatical. As a music teacher and leader in the community, Rose was involved in community theater, served on the County Council on the Arts, and had done many musicals with the children in the schools. The superintendent called her in and asked what she was going to do on sabbatical. She replied that she had been accepted into SUNY Albany’s program in children’s theater and that she had been accepted at Columbia University’s Teacher’s College. The superintendent replied, “You are going to Columbia. I’m not going to pay you to go off and be an actress.” So, she went to Columbia.

After earning the doctorate, Rose became a professor. She received her first appointment as an assistant professor at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas. Although she and her husband and two sons moved there for the job, Texas, with the prejudice, de facto segregation and sexism they encountered was not for them. The family left after a year and Rose began a satisfying academic and administrative career at SUNY New Paltz where she is Professor Emeritus. Currently Rose is Professor and Program Director of Educational Leadership, Mercy College, NY. Rose also belongs to a protest brass band, the Tin Horn Uprising, named for an uprising of tenant farmers in the Hudson Valley in the 19th century.