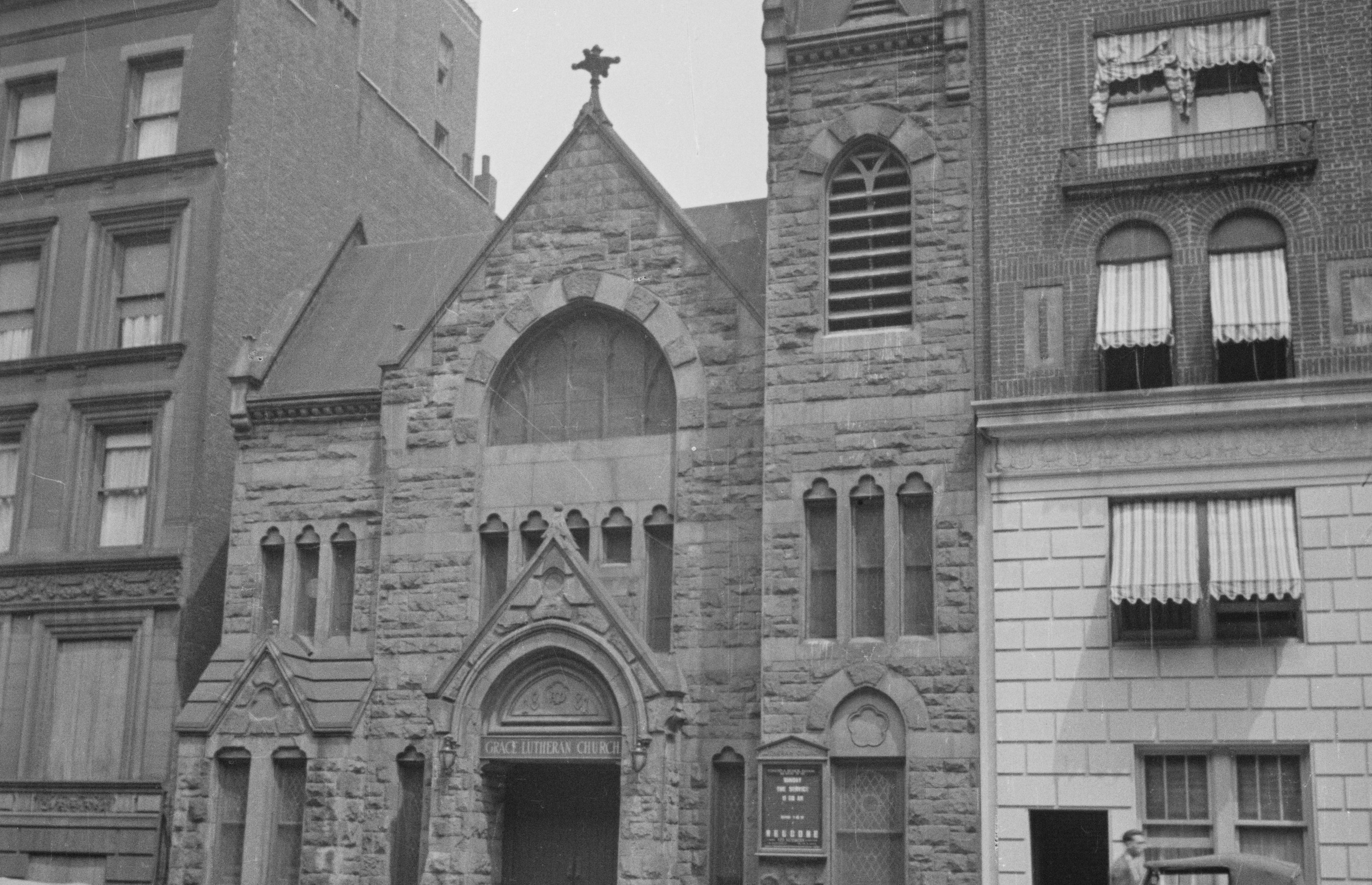

Grace and St. Paul’s Church

123-125 West 71st Street

by Tom Miller

As the Upper West Side rapidly developed, churches—Roman Catholic, Episcopalian, Lutheran, and Presbyterian among them—scrambled to establish missions and chapels for the expanding population. In 1880, the Methodists joined the movement.

The Methodist Episcopal Church had already established a mission chapel far to the north, in Harlem. The need for a church there was the result of the same change that caused the building boom on the Upper West Side—improved transportation. On December 26, 1879, the Rev. W. S. Blake of Grace Chapel on 104th Street told a meeting of the New-York City Church Extension and Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church that “his people relied upon two things—Providence and the elevated railroads.”

Only a few months later, the Missionary Society acquired the vacant lots at Nos. 123 and 125 West 71st Street, between Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues. Within the year architect Stephen Decatur Hatch was at work on the design.

The architect of the United States War Department in the 1860s, Hatch’s career had flourished by now. He was well-known for his large commercial buildings like the Gilsey House Hotel and the Robbins & Appleton Building. The stone ecclesiastical structure on West 71st Street would be far more intimate.

Construction began in 1881 and was completed a year later. St. Andrew’s Chapel was deemed by King’s Handbook of New York City “a neat stone chapel.” Hatch used rough cut blocks, more expected in Romanesque Revival churches, to create the charming and bucolic brownstone church–deemed by some architectural historians “High Victorian Gothic.”

Three stories tall, its angles, gables and bell tower were the epitome of 1880s architectural taste. Hatch filled the top of the central gable with quilt-like stonework, borrowed from the currently rampant Queen Anne style.

The blocks around St. Andrew’s Chapel filled with upscale rowhouses. By 1895, its membership was sufficient for the Missionary Society to consider elevating St. Andrew’s to church status. Minutes of the meeting of the Board of Managers on May 8, 1865, recorded the opinion that “the neighborhood of the church was rapidly filling with the residences of intelligent and prosperous citizens; and that the dignity and influence of the Church would be materially increased” by organizing St. Andrew’s own Board of Trustees. A month later, on June 12, 1885, the chapel became St. Andrew’s Methodist Episcopal Church.

The pulpit in the 19th century was often used as much to preach the Gospel as to vent the political opinions of the clergy.

As with most other churches, St. Andrew’s not only ministered to the souls of the residents but to their minds. Lectures and concerts were presented here, such as the “musical reception” given on the evening of April 22, 1887. The announcement said, “Miss Ida W. Hubbell, Miss Adelaide Foresman, Miss Kate Chittenden, Arthur D. Woodruff, Francis Fisher Powers, and Charles A. Stevenson are the artists who will appear.”

The pulpit in the 19th century was often used as much to preach the Gospel as to vent the political opinions of the clergy. And so it was on Sunday, March 30, 1889, when the enraged pastor Rev. Dr. James M. King lashed out against proposed public school legislation.

“I want to protest against the niggardly and criminal spirit that expends vast sums of money for political jobs of all sorts and does not furnish ample, well-appointed schoolrooms. The city is literally making vagrants by the hundred, and it is a travesty on common sense to pass vagrant and truant laws, compelling children to attend school when multitudes of them can’t get into schools if they try.”

Reverend King’s sermons from West 71st Street were coming to an end. On May 27 that year, the New-York Tribune reported that the pastor had commissioned J. C. Cady & Co., “the well-known architects of No. 111 Broadway,” to design a new church on the south side of West 76th Street. The newspaper promised, “The church architecture of this city will be enriched in the course of the present year by an example of great beauty.”

The “farewell service” was held in St. Andrew’s Methodist Church on the night of March 16, 1890. On April 26, the Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide reported that the 71st Street church had been delivered “vacant” to John T. Farley for $40,000 five days earlier. The price, about $1 million today, would help offset the $100,000 cost of the new St. Andrew’s.

Farley was a trustee of the four-year-old Lutheran Gnaden Kirche or Grace German Lutheran Church. While the German population of New York City was centered on the Lower East Side and, to a lesser extent at this time, in Yorkville, the German Lutheran community on the West Side was sufficient to support the church.

On May 20, 1893, The New York Times reported that “Pfingsten, Whitsuntide, and Pentecost mark to-day among the Germans the opening of the season of Summer festivities.” In language considered somewhat questionable today, the newspaper said: “They signify that the dreary Winter and showery, windy Spring are at an end, and that it is time for the Teuton to take his wife and children or his best girl out into the green fields under the blue, sunny sky.”

The Times said, “This custom of the Fatherland German adopted citizens in the United States have kept up through all the many years that they have lived here, and most of their children, who have been born here and have now grown up as full-fledged Americans, also observe the festival.”

In mentioning the services at the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Grace, the newspaper said, “Germans who are not connected with any church have been invited to attend these services.”

Like the Reverend James King had been, the Reverend George U. Wenner was displeased with the public school system. On January 30, 1906, he told a meeting of ministers in the United Charities Building of the alternative he had established at Grace Church. The penalty for not attending was severe.

“With a deaconess and his sexton, who holds a teacher’s certificate, he had arranged six graded classes for his children. Every afternoon at 4 o’clock there is one hour of instruction and every Saturday at 9 o’clock two hours. The older children get two hours teaching per week, the younger one hour, and if they will not attend they are excommunicated.”

Under the pastorate of John Andrew Weyl the congregation weathered the uncomfortable World War I years. At a time when German-born New Yorkers were required to register as “enemy aliens,” the services continued to be conducted in German.

On Valentine’s Day, 1924, a massive fire tore through the Church of Grace, essentially gutting the interiors. Damages amounted to around $25,000.

Reverend Weyl would continue to lead the Lutheran Church of Grace until 1931—a remarkable 35 years in the pulpit.

He was succeeded by the Rev. Edmund A. Bosch, who preached his first sermon here on July 1, 1934. It was a fiery speech that would set the tone of his leadership. The New York Times reported the following morning, “Gangsters, corrupt politicians and munitions manufacturers, he said, perhaps had placed the average American citizen under the bonds of servitude akin to slavery.”

Bosch’s father, the Rev. Frederick H. Bosch, was pastor of the St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, uptown at No. 147 West 123rd Street. The familial connection would play an important part in the history of both churches later on.

At the time, Walter Ziegfried, the church’s caretaker, had a room on the first floor of the church. Tragically, at around 6 p.m. on February 16, 1935, the church organist, C. A. Anderson, discovered the 40-year-old dead on the studio couch in his room.

On Valentine’s Day, 1924, a massive fire tore through the Church of Grace, essentially gutting the interiors.

With the windows closed against the cold winter air, Ziegfried had not noticed that the flame in the gas water heater had blown out. Unaware, he was overcome with the gas that slowly filled the small room.

By the spring of 1940, the Harlem neighborhood around St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church had changed. The German population had dwindled to the point that it could no longer support the church. On March 6 that year, The New York Times reported that the 123rd Street building had been purchased by “The Negro group known as the Twelfth Church of Christ, Scientist.” The newspaper added that St. Paul’s would be “now affiliated with the Grace Lutheran Church at 123 West Seventy-first Street.”

Rev. Frederick H. Bosch and his son, Edmund, now shared the pulpit of the Church of Grace. But the co-pastorate would be short-lived. On March 30, 1941, with World War II raging in Europe, the Rev. Edmund Bosch gave his farewell sermon. “He has been called to serve as chaplain with the Regular Army,” reported The Times.

As it had decades earlier, the German church continued on through the war while enduring heavily anti-German sentiments. By now, however, the congregation was mixed, and while Rev. Frederick Bosch continued to conduct one service in German, other ministers delivered sermons in English. The two congregations were officially merged on September 28, 1944, when the name was changed to Grace and St. Paul’s Church.

After serving St. Paul’s for 40 years and the combined churches for five, Frederick H. Bosch died at the age of 73 in 1944. His funeral was held in Grace and St. Paul’s Church on the evening of April 4.

When the church welcomed a new pastor on October 14, 1951, newspapers took notice less because of the Rev. John Urich’s ability, than because of his disability. The New York Times headline read, “Blind Man Takes Lutheran Pulpit.” The newspaper noted, “His wife, also blind, assisted him in greeting parishioners afterward.”

Urich, who had been blind from birth, proved to be a strong and beloved pastor. His affliction was rarely mentioned; other than instances like that on September 27, 1954, when the church was visited by 75 blind worshipers. He served as pastor for seven years until his death in 1958.

As early as 1961, the church presented plays. On January 29 that year Mary Magdalene was staged by the Vesper Theater. Then, in 1973, it became the initial home of a professional theater group sponsored by local artists and the community called Grace and St. Paul’s Church Theater.

A more than $1 million restoration and renovation was begun in 1988. Hemmed in by towering buildings, Hatch’s picturesque chapel is easily overlooked, yet it continues to serve the neighborhood of “intelligent and prosperous citizens” as it did 145 years ago.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Explore Houses of Worship

Be a part of history!

Stay local to support the nonprofit currently at 123-125 West 71st Street: