361 Central Park West

View of 361 Central Park West from northwest. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

Former First Church of Christ, Scientist

361 Central Park West, aka 1 West 96th Street

by Tom Miller

In the years following the Civil War, Mary Baker Eddy conceived of a new theological approach—one which focused on the spiritual and deprecated the material. Her new organization, the Church of Christ, Scientist, grew despite detractors who dubbed it a cult—mainly because of Eddy’s conviction that illness should be healed through faith rather than man-made medicine. In 1886 she sent her close friend, Mrs. Augusta E. Stetson, to New York to organize the first Christian Science movement in the city. Stetson was a tireless worker–authoritative, charismatic, and convincing. The New-York Tribune later wrote “Mrs. Stetson, after a labor of two years, organized the First Church in this city in 1888.”

Augusta Stetson was the first minister of the church. As her New York church grew, so did her power and influence. Stetson found both to be addicting and exhilarating. The congregation outgrew its first rented hall at the corner of 47th Street and Fifth Avenue and moved to another hall at No. 138 Fifth Avenue. Continued growth prompted its move to Hardman Hall at Fifth Avenue and 19th Street; then to the old Rutger Presbyterian Church on Madison Avenue and 29th Street. Three years later the church moved again. In January 1896 it acquired the All Souls’ Church on 48th Street. But under Augusta E. Stetson’s energetic ministry the congregation continued to swell. In 1899 land was purchased on the corner of Central Park West and 96th Street as the site of a new, permanent church structure. Augusta Stetson eyed the top of the heap in choosing her architects. All of New York City was watching Carrere and Hastings’ monumental white marble New York Public Library take shape on Fifth Avenue. The firm was now contracted to design the new First Church of Christ, Scientist.

The cornerstone was laid on November 30, 1899. In it was placed a letter from Mary Baker Eddy to Augusta Stetson that read “Beneath this cornerstone, in this silent sacred sanctuary of earth’s sweet songs, paeans of praise and records of omnipotence, I leave my name with thine in unity and love.” Later, the Architectural Record would note, “The building finally produced has been to a remarkable degree a development rather than the fulfillment of a formulated plan.” Indeed, the $300,000 budget initially laid out soon was left far in the dust. “Not content with brick and Indiana stone, Concord granite was ordered, though the cost of this material in itself, when set and under roof would be $400,000,” said the Record. The white stone, quarried in Concord, New Hampshire, was valued for its characteristic of not discoloring when exposed to air; but rather to grow whiter, because of its extreme hardness, it could not be cut by saw or machinery and hand labor for cutting was necessary—adding to the expense. Then came the reading room, Sunday school rooms and offices that were not included in the initial plans. The cost rose to $550,000. But Christian Science ideals did not approve of these rooms being housed in the basement, so more changes were made and they were moved above the auditorium and three elevators were added. The estimates now had risen to $750,000.

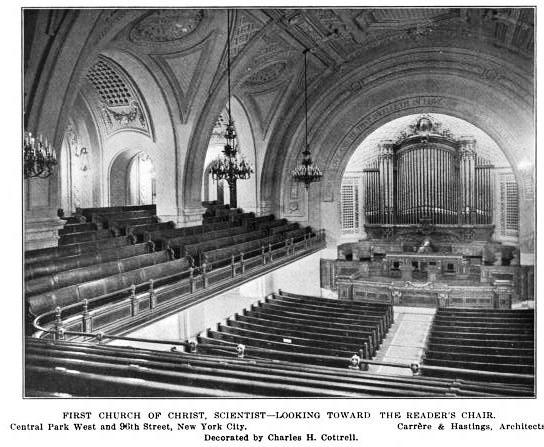

Despite Christian Science’s censure of the material, “It was then discovered that a tower of a more expensive design would add to the beauty of the structure and this was also ordered,” reported Architectural Record. “Finally, all limitations were ignored, new features were added as they were required to make the church more perfect in beauty and utility.” When the church was dedicated in 1903, the cost had topped out at $1.185 million. Through Augusta Stetson’s unstinting fund raising the church was entirely paid for when its doors were opened. The congregation totaled 1,200 members; but it had no intentions of moving again soon. Carrere and Hastings had designed an auditorium that would accommodate 2,200 worshipers.

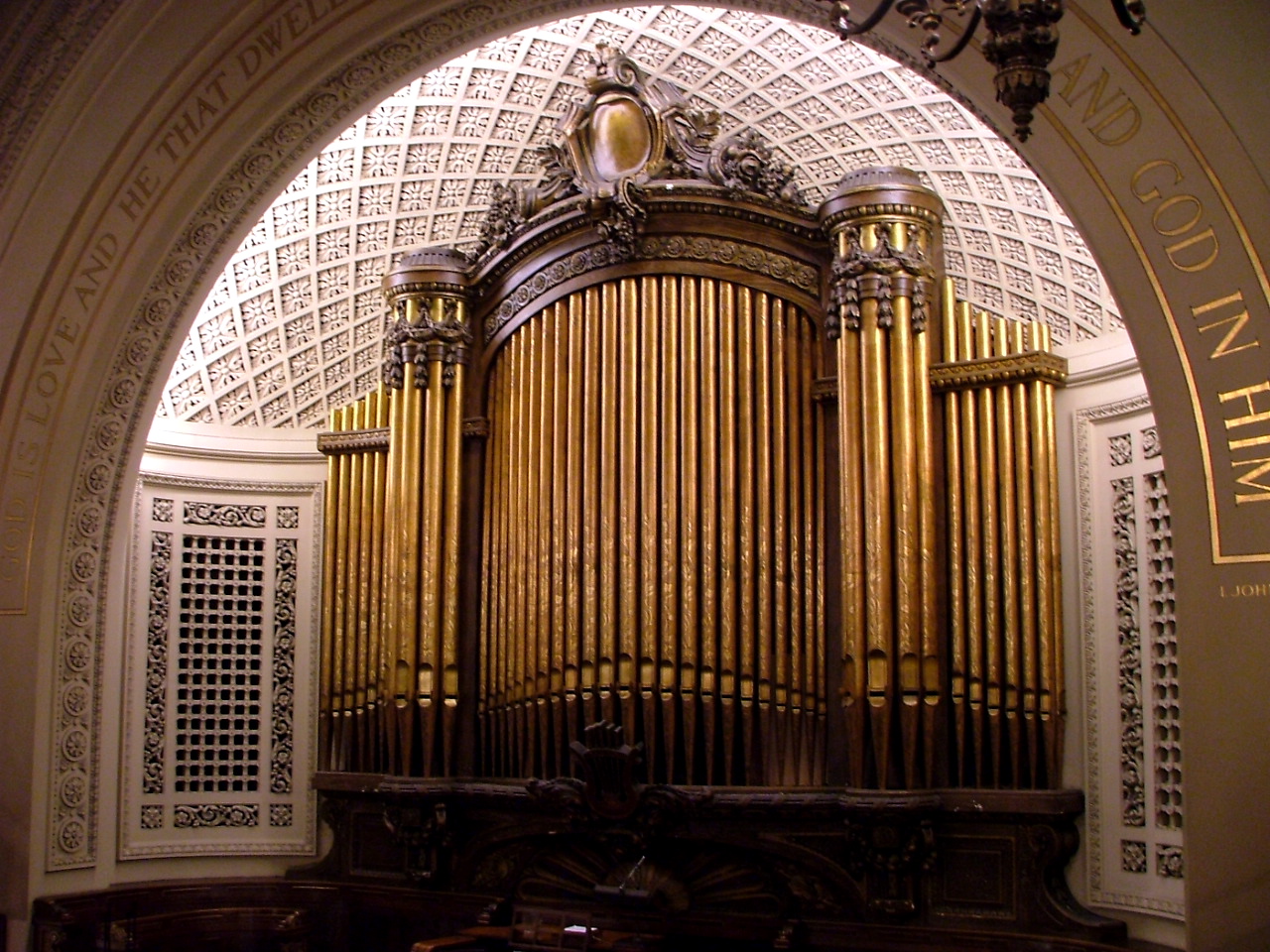

The finished church was imposing and dignified. The granite steeple—which rose to a blunt rather than pointed end–rose 200 feet above the sidewalk. The massive corner cornice stones were 12 feet long, 8 feet wide and 3 feet, 6 inches thick—each weighing 18 tons. Architectural Record called it New York’s “most imposing church edifice;” a “beautiful picture in glistening silvery white granite; stone, so uniform in color and quality, as at once to give one the impression that the whole must have been cut from one huge perfect block.” The interior was decorated by Charles H. Cottrell who, too, was unswayed by the church dogma regarding materialism. The auditorium was clad in marble and six large chandeliers, each weighing over half a ton, illuminated the space with 78 electric bulbs each. The Architectural Record said “These fixtures are probably the finest example of a public chandelier in America.”

Even before construction started, the Boston Mother Church was having issues with Augusta Stetson. The New-York Tribune reported later “Mrs. Stetson’s preaching in the New York church had naturally brought her reputation and power. In ‘The Christian Science Journal’ of April, 1895, therefore, Mrs. Eddy announced that preachers would no longer constitute a part of the machinery of her Church, and that their place would be filled by a first and second reader.” Augusta Stetson obliged and became first reader. “Her power, instead of decreasing with her curtailed opportunities, increased in spite of the fact that she was bound to a rigidly prescribed reading of the printed words from Mrs. Eddy’s book, ‘Science and Health,’” noted the Tribune. Then a bylaw was enacted, in 1902, limiting a reader’s term to one year. Even now, with her post as first reader taken away, Augusta Stetson wielded great sway and by the eve of the church’s dedication, the tensions between her and Boston were being noticed.

The white stone, quarried in Concord, New Hampshire, was valued for its characteristic of not discoloring when exposed to air; but rather to grow whiter, because of its extreme hardness, it could not be cut by saw or machinery and hand labor for cutting was necessary—adding to the expense.

The friction between Stetson and the First Church

On November 28, 1903, the day before the dedication The Evening World reported “Christian Scientists, not only of the First Church, but all over the city, are expressing indignation to-day over the anonymous and groundless attack printed in most of the morning papers on Mrs. Augusta E. Stetson…This attack said that there was great friction which threatened to disrupt the First Church; that Mrs. Stetson posed as a dictator and arrogant leader and condemned her policy in refusing to join with the other churches in a downtown reading room.”

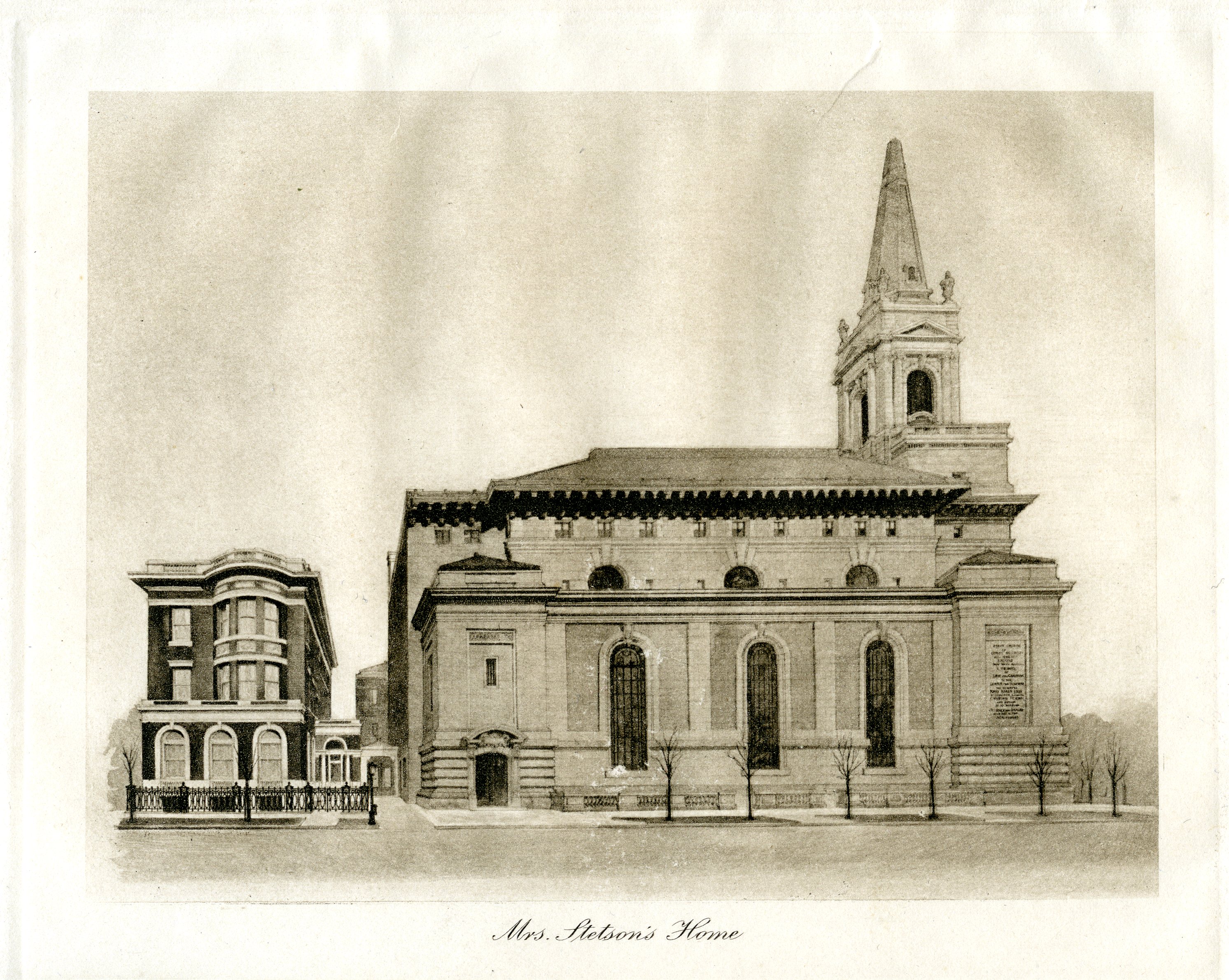

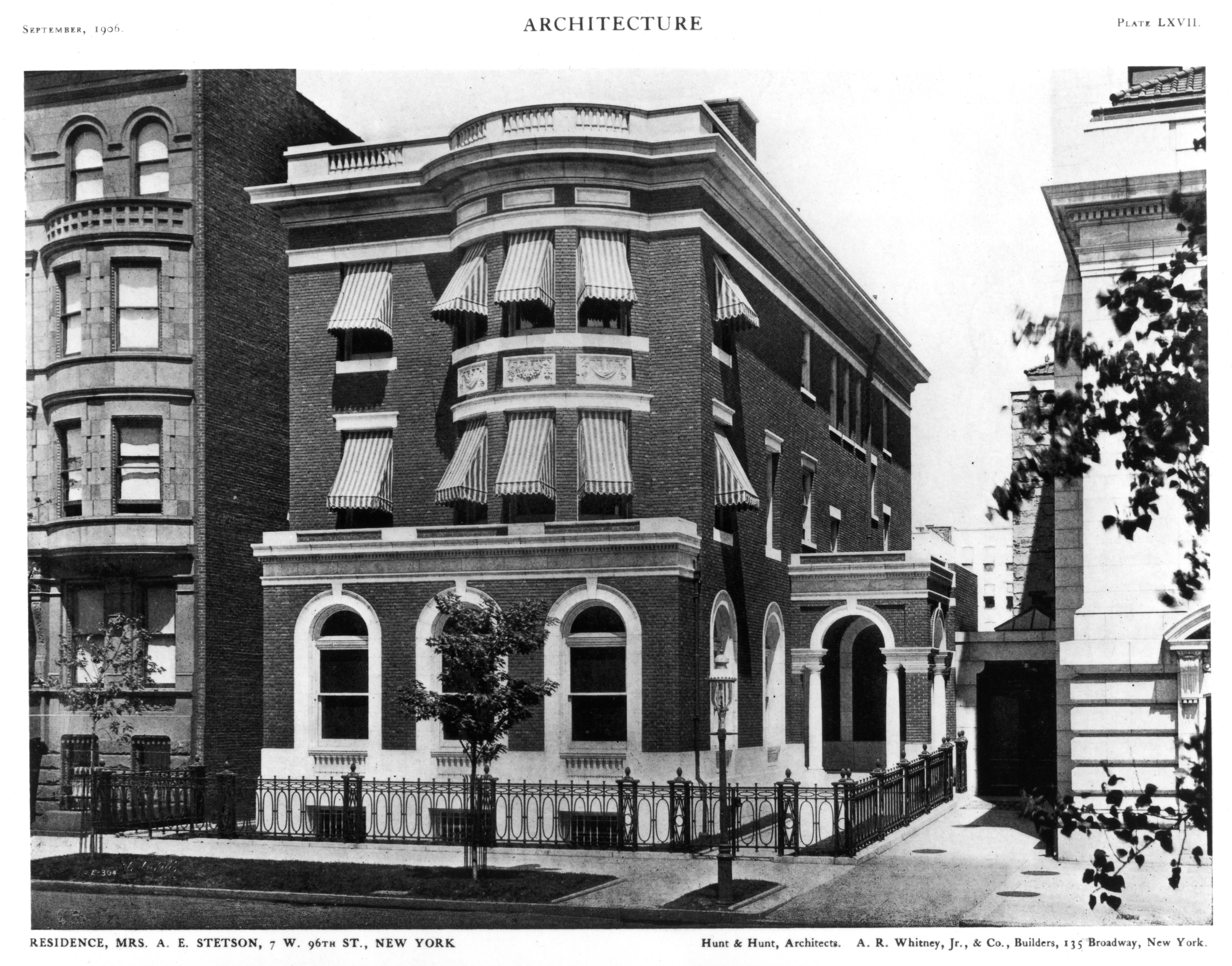

A year after the dedication, Augusta Stetson purchased the land immediately behind the church and commissioned architects Hunt & Hunt to design a white marble mansion. On December 22, 1904, The Evening World reported that “The plans show that the house, which will be of marble…will cost $35,000. There will be a one-story portico entrance on the side which will be ornamented with marble columns.” Mrs. Stetson’s new house would cost, in today’s dollars, about $700,000. She signed a contract with the church giving it first opportunity to buy should the house come onto the market.

Despite her ability to draw members and increase the church’s coffers; Augusta Stetson was heavy-handed and nearly tyrannical. While the Boston contingent tried to rein her in, “She still remained the actual leader,” recalled the New-York Tribune in 1910, “and in 1908 she demonstrated the strength of her leadership when it became known that she had formed elaborate plans for the erection of a church on Riverside Drive, near 86th Street.” This would be the Second Church of Christ, Scientist. “The announcements of this undertaking disclosed that the new church would be the most magnificent church edifice in the world.” Stetson had, perhaps, dropped the last straw on the camel’s back. A bylaw of the Mother Church forbade a branch church, such as First Church, to establish its own branch, such as Second Church. The Mother Church officials condemned the project and the plans were dropped. The damage, however, had been done.

In September 1909, “Mrs. Stetson’s card as a healer, together with those of her students who are also healers, was removed from one of the official journals of the denomination,” reported the New-York Tribune. Then, on November 19, 1909, the New-York Tribune ran the headline “Mrs. Stetson Out.” The Mother Church excommunicated her, barring her from the church she had built. The Tribune said that “Excommunication is rarely resorted to in the Christian Science Church, and in view of Mrs. Stetson’s prominence today’s action was regarded in Church circles here as the most drastic in the history of the denomination.” She was charged with “malpractice” and with having put “personality above principle.”

The proposal of a ‘spite fence’

The Church of Christ, Scientist had not heard the last of Augusta E. Stetson. She continued to preach from her parlor to adherents whom the newspapers deemed “Stetsonites.” In July 1910 sixteen practitioners “who were identified with and supported Mrs. Augusta Stetson in her controversy with the First Church of Christ, Scientist” were also dropped from membership by the Boston directors. A month earlier fifteen other members had already had been dropped from the church’s membership. Later that year Augusta Stetson must have enjoyed smug vengeance upon the reading of Mary Baker Eddy’s will. On December 19 The New York Times ran an article headlined “Mrs. Eddy’s Jewels Go To Mrs. Stetson.” Eddy had left Augusta Stetson her “crown of diamonds” breastpin; a token of friendship even after all that had passed.

With Mary Baker Eddy gone, Stetson opened the debate as to who should take her place at the head of the church. Stetson audaciously asserted that she was the spiritual successor of Mary Baker Eddy. She put forth her opinion in 1913 in a 1,200 page book. “Temporarily, at least,” reported The Times, “the Trustees of the local church and members of the Christian Science organization decided to ignore Mrs. Stetson. Her opinion and assertions were put forward in a volume which she has been writing in the four years in which she has seen the throngs passing under her window to the Christian Science Church, next door to her home, while she was forced to sing her hymns and read her lessons to herself.”

Augusta continued to be a thorn in the side of the church. In December 1920 the memberships of the “Stetsonites” who had been banished were ordered by the courts to be reinstated. The judgment said in part that they “were dismissed on the flimsy pretext of non-attendance.” In what could appear to be retaliation, the church laid plans to build a wall between its property and Mrs. Stetson’s. Because her ornate cast iron fence technically straddled the property lines, it would have to go. Augusta Stetson armed for war. A series of heated letters were fired back and forth across the property line and somehow were leaked to the press. Both parties cloaked their positions as supporting what Mary Baker Eddy would have wanted. At least in the beginning.

Stetson wrote, for instance, “This proposed infringement concerns those who, in love for the Cause and for their Leader, Mrs. Eddy, sacrificed their money and their time, and united with Mrs. Eddy and with me, in erecting this Church. Therefore I feel obliged scientifically to consider their protection, and shall appeal to my God, whom I serve continually, to defend them and me, through avenues whom He, God, may choose to execute his law of justice and equity.” Finally, in September 1921, Augusta Stetson took the gloves off. When workmen appeared on the grounds of the church, she went to court. Her attorney called the proposed wall “a spite fence” and succeeded in obtaining a restraining order, stopping construction of the 15-foot high wall.

The judge said in part that the wall ”would be violative of the rights of Mrs. Stetson, that it would serve no useful purpose and would constitute an architectural monstrosity.” As years passed, Augusta Stetson clung on to her aspirations of succeeding Mary Baker Eddy. Unable to espouse her views within the church, she turned to a campaign of advertising. According to The New York Times, “Between 1920 and 1925, she is said on good authority to have spent more than $750,000 in newspaper advertising alone. These announcements were in the form of sermons, comments on letters or articles in which she defended her teaching of Christian Science and sought to prove that she was following in Mrs. Eddy’s footsteps and had been delegated by the founder as the Church’s leader.” But in her later years, her ideas grew strange.

In 1927, she announced the coming of the millennium and said “likewise, that she herself was immortal.” Her belief that “her body as well as her soul would never die” proved inaccurate on October 12, 1928, when she died after ten weeks of illness. The Times said in her obituary, “Around her centered a great internal quarrel which at one time threatened to disrupt the Church, although she always insisted she was merely preserving Mrs. Eddy’s teachings and had no intention of creating a schism.” The First Church of Christ, Scientist wasted no time in taking advantage of its option to buy Stetson’s marble mansion. It quickly resold the property to the Sprevbel Realty Corporation for $180,000. All ties between the church and Augusta E. Stetson were finally severed.

In what could appear to be retaliation, the church laid plans to build a wall between its property and Mrs. Stetson’s. Because her ornate cast iron fence technically straddled the property lines, it would have to go. Augusta Stetson armed for war.

Ungodly transformations

The First Church of Christ, Scientist settled into decades, finally, of no undo publicity. It appeared in the newspapers once again in 1989 when Larry Hogue, a homeless man of the neighborhood, descended into a drug-induced rage. Residents had noticed his mental illness worsen over a period of years. More than a dozen times police had taken him to psychiatric emergency rooms or to jail following violent outbursts; but he always returned to the neighborhood. Delirious on alcohol, cocaine or some other drug, he began smashing rocks through the stained glass windows of First Church of Christ, Scientist. Before he could be stopped he had caused between $10,000 and $20,000 in damages.

In 1993 the congregation was still in the process of repairing the windows as well as correcting problems with the granite steeple. The problem was money. The congregation that Augusta Stetson had grown to 1,200 now had about 30 or 40 people at Sunday services. The New York Landmarks Conservancy awarded the church an $80,000 grant to determine the extent of damage and recommend repairs. In May 2001 the First Church of Christ, Scientist building became home to the Crenshaw Christian Center East. The Center is a branch of the ministry founded by Pastor Frederick K. C. Price in South Los Angeles on the site of the former Pepperdine University campus.

In 2014 the Crenshaw Christian Center sold the historic church for $26 million; a tidy $12 million more than the California-based center had paid for it. Because the building is protected by landmark status, it could not be destroyed. But its century-old interiors could be. The purchasing developer announced plans to convert the historic structure into between 20 and 30 luxury residences. The only restrictions, since the interiors are not landmarked, were that the facade must remain intact and intrinsic details like the stained glass windows be preserved. The massacre of this beautiful and important structure was just the latest in a string of ungodly transformations of historic religious buildings into posh residential projects. A preservation movement spearheaded by Landmark West! blocked the conversion to apartments. In 2018 the building was purchased by the Children’s Museum of Manhattan as its new home.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Return to Central Park West

Landmarks Timeline

Return to Spirit of the City

Building Database

Designation Report