Nodding to the past and embracing innovation is a recurring theme guiding architects of post-war buildings on the Upper West Side. There have been detours, some more successful than others. A few plain-faced white buildings introduced in the 80s and 90s have had limited enduring attraction for some and none at all for architect James Davidson, Architect, SLCE Architects, who designed the Laureate on 76th Street and Broadway and The Coronado at 155 West 70th Street.

Recently, when talking with Davidson, it’s clear that while designing the Coronado, he cared about the rich hue and texture of brick, but he was equally interested in having the building’s aesthetic fit with its neighbors. So like what, for example? Davidson noted that “many of the neighborhood’s buildings and wrought iron fences are gray or dark gray.” His interest in relating his design to the color and character of pre-war buildings is reflected at the Coronado in exterior details like the gray color of the window frames. Other features informed by the past include many graceful recessed bay windows and Juliet balconies that align well with the contemporary urban lust for a bit of personal outdoor space. It’s impossible to miss that scores of Upper West Side brownstones and apartment buildings are notable not only for fanciful gargoyles but for naturalistic sculptural faces and figures of humans that form a bridge between flesh and blood community residents and the granite, limestone, brick, terra cotta, and cement buildings that surround them. Particularly noteworthy in this context is the importance of Coronado’s entry – a significant asset for this “standout building.”

Jeffrey Katz, CEO of Steadman Enterprises and developer of the Coronado, took a deep personal interest in all the details of its design. As he conveyed recently, he was especially interested in the marquee canopy above the front entry. This architectural component was integrated with the installation of two gargoyles above the canopy: fierce winged dogs that symbolically protect residents and ward off evil. “We stole the idea from 16th Century traditions,” Katz said. The Coronado’s gargoyles are made of molded granite.

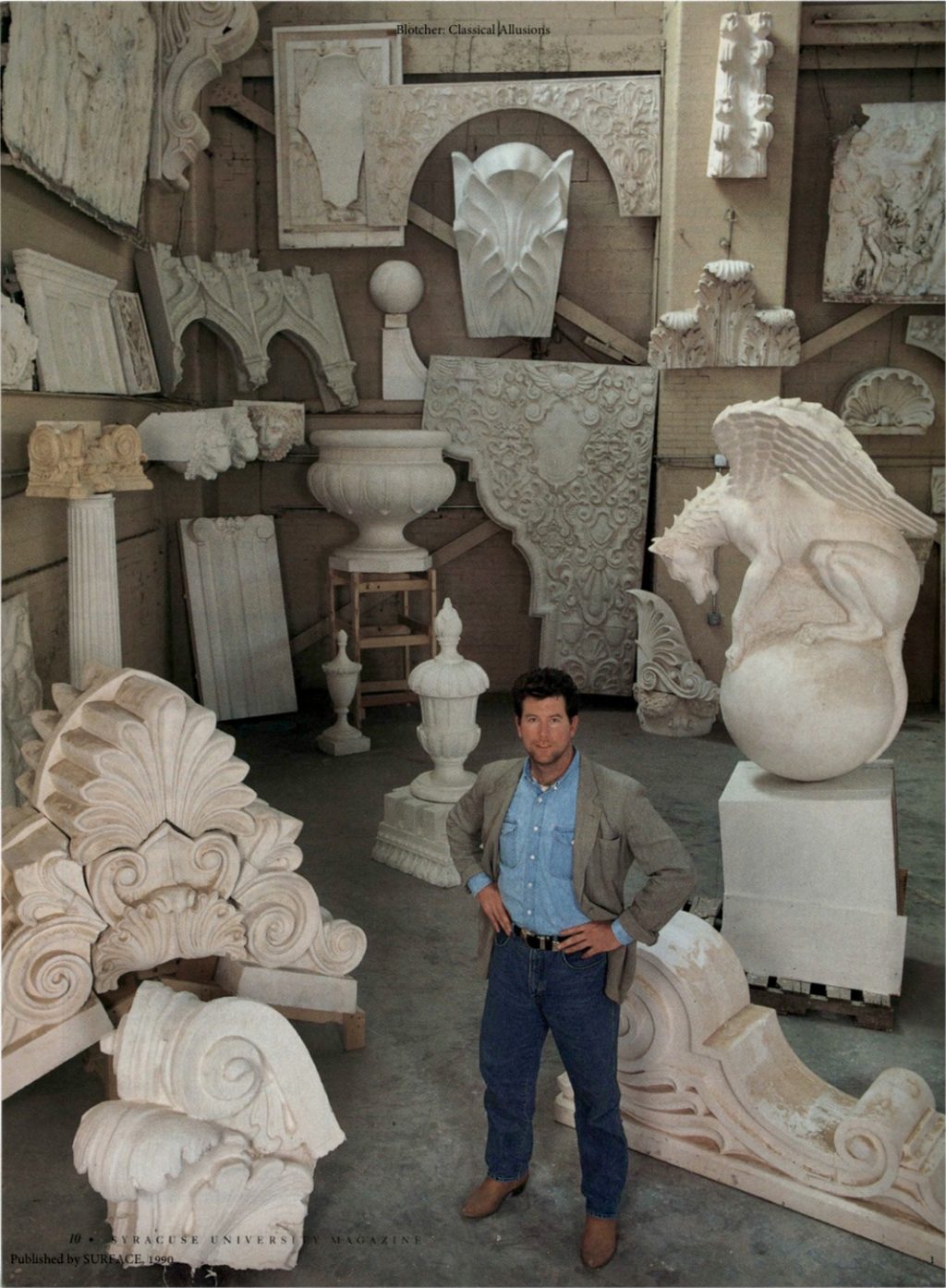

After coming up with the concept for the entry, the developer recalled searching for an artist who could execute it. They identified Mike MacLeod, a sculptor who ran MJM Studio, an architectural sculpture firm with 40 employees in South Kearny, New Jersey. Reflecting on the finished gargoyles, Davidson admitted, “I found them a tad too big.” But, the developer was pleased both with the size of the stone-winged dogs that complemented the port cochère, also designed by MacLeod.

After coming up with the concept for the entry, the developer recalled searching for an artist who could execute it. They identified Mike MacLeod, a sculptor who ran MJM Studio, an architectural sculpture firm with 40 employees in South Kearny, New Jersey. Reflecting on the finished gargoyles, Davidson admitted, “I found them a tad too big.” But, the developer was pleased both with the size of the stone-winged dogs that complemented the port cochère, also designed by MacLeod.

Davidson noted the canopy was inspired by the one that is a designated landmark at the Path Station in Greenwich.

The sculptor expressed his satisfaction with the project in a 1990 article by Jay Boutcher. “MacLeod chuckles at the intimidating sentries, crafted in the tradition of gargoyles and griffins. Cheery canines wouldn’t have worked. To fulfill the original purpose of keeping away evil spirits, you’d have to be a pretty bad dude.”

On the topic of grandeur, The Coronado’s gargoyles were dwarfed by the nine monumental life-size sculptures of Indian elephants, painted white with gold flourishes that MacLeod sculpted around the same period for Trump’s Taj Mahal Casino in Atlantic City. Macleod was among other workers who protested in the media that they were shortchanged for the work they did at the hotel-casino. Almost two decades later, after the hotel-casino was purchased by the owners of the Hard Rock Cafe, some or all of MacLeod’s elephants were for sale on the beach in Miami as part of the 2017 Art Basel show. In contrast, enduring without controversy, the granite gargoyles remain a showpiece at the Coronado. “They’re jewelry for the building,” said Katz.

Curious as to what became of MacLeod? A 2017 video described his life as an artist in a small town in Argentina. A related article describes him as having found a perfect setting in which to live and work. An English translation of an interview with MacLeod by Carlos notes that Macleod decided to move to La Cumbre, where his wife comes from.

“I came to live at La Cumbre in the middle of a decision that was to be an artist in Argentina. Looking for a way not to lose my essence, to continue being myself without being connected to big projects…I like this place where I am now because it keeps you connected with the essence…Being here and in this way allows me to forget about thinking about business and simply being creative,” says the artist who chose La Cumbre as his earthly paradise.”

NOTE: Photo of Sculptor Mike MacLeod in his studio via Syracuse University Magazine.

By

By