212 West 93rd Street

Congregation Shaare Zedek

212 West 93rd Street

by Megan Fitzpatrick

Shaare Zedek is celebrated as the third oldest Jewish congregation in New York City, first established in 1837 by Polish immigrants. Its history is well documented in Jacob Monsky’s Within the Gates, written on the occasion of the congregation’s 125th Anniversary. The congregation moved around Manhattan until ultimately settling on the Upper West Side. Unfortunately, the former historic building on 93rd Street was demolished only six years ago and replaced with a 14-story condominium, an all too familiar trend in recent years.

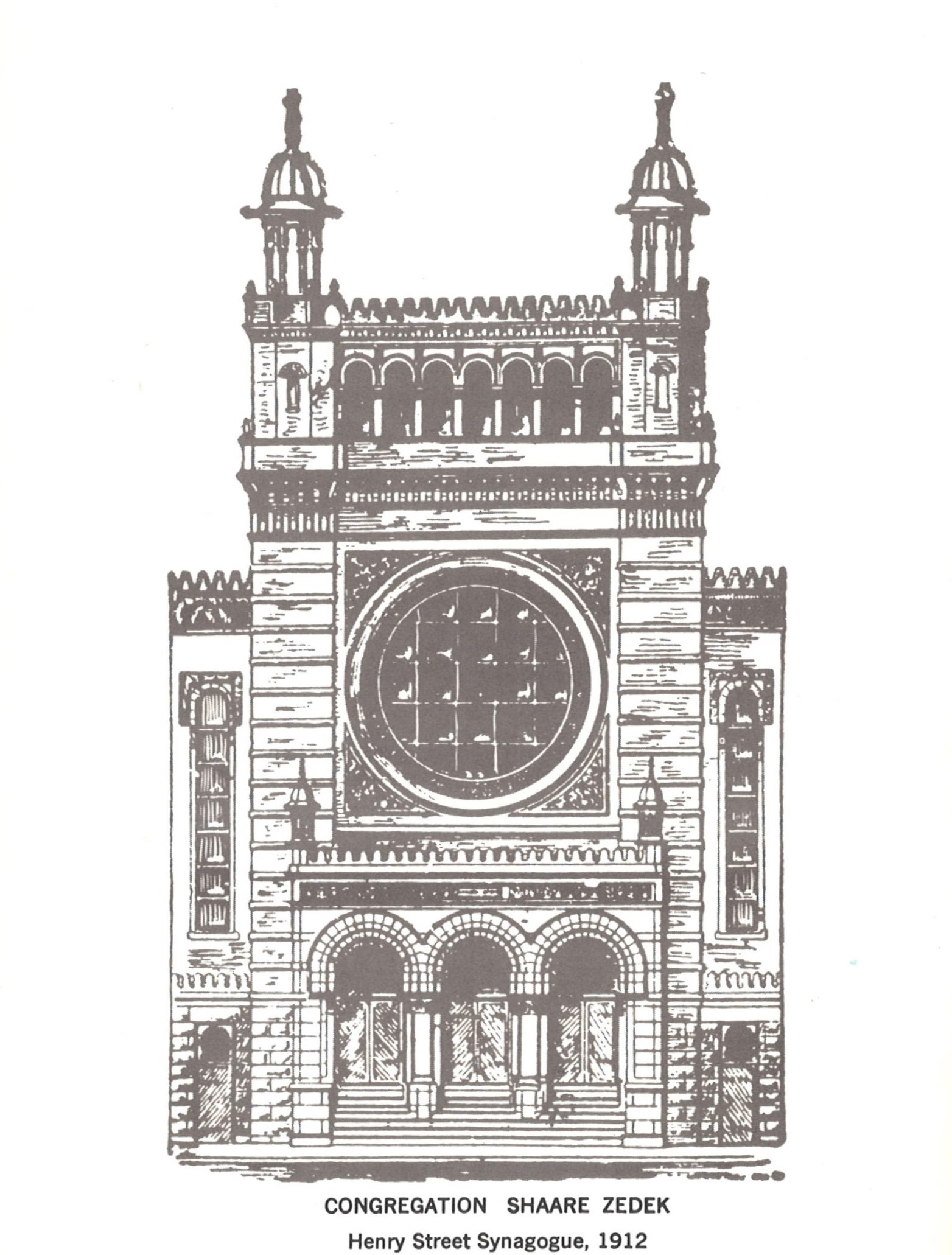

The congregation was first established in 1837 with an initial meeting of Polish immigrants at 42 Water Street, Manhattan. As the congregation grew, they moved to a rented space at 472 Pearl Street in the Lower East Side before setting their roots just a few blocks away at 38-40 Henry Street, where they built their permanent home from two plots of land leased by Congregation Ansche Chesed (sznyc.org). The Henry Street location is where the congregation formed who they were, their values, and also their disagreements.

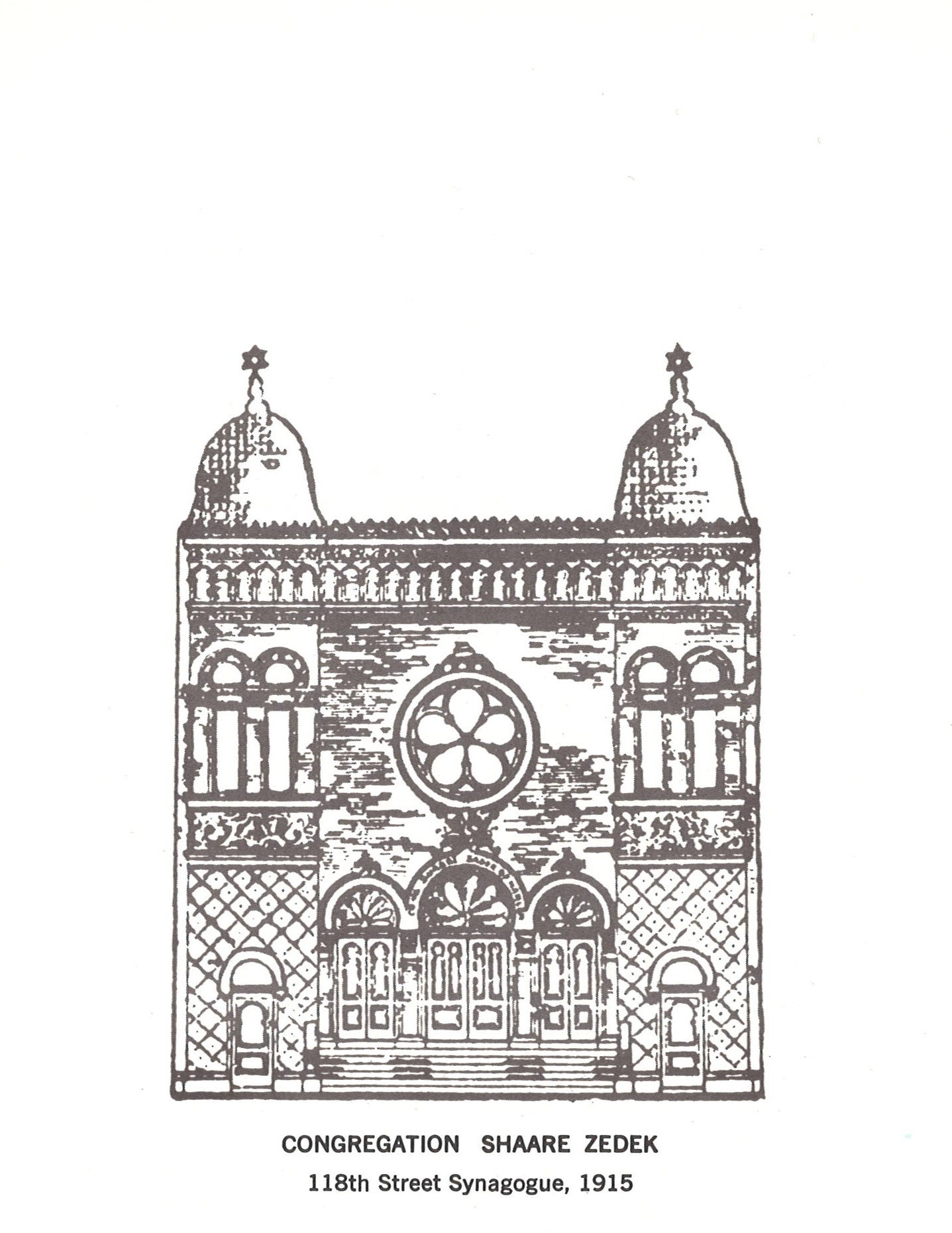

A major split occurred at the turn of the century causing a section of the congregation to move uptown to Harlem and form a separate congregation but still under a shared name. This followed the general trend of Jewish congregations moving uptown. They began worshiping at 25 West 118th Street (now the Bethel Way of the Cross Church of Christ). After the Henry Street synagogue was sold in 1911 for $60,000, the original congregation also moved to Harlem, renting the New York Presbyterian Church on West 128th Street (Dunlap, 2004, p. 260). Now in one central neighborhood, the congregation was reconciled and amalgamated around 1914. However, membership of the now reunited congregation overwhelmed capacity at the 118th Street synagogue. Therefore, they focused on finding a suitable place to worship for the expanding congregation.

Establishment of building on 93rd Street

On October 31, 1921, the congregation purchased land on the south side of West 93rd Street, costing $100,000. A building committee was established by trusted members of the congregation to mitigate the serious problem of capacity and to achieve three goals with this new shul: the building must meet religious needs, its structure and materials must be durable and aesthetics must be appropriate. The members originally discussed the possibility of building a five-story structure containing a school, banquet hall, gymnasium, and water pool costing approximately $775,000. Jacob Monsky writes that ‘arguments and frustrations were many’ regarding this decision but the congregation ultimately decided upon a $300,000 three-story structure with a large auditorium and balcony (Monsky, 1964, p. 89).

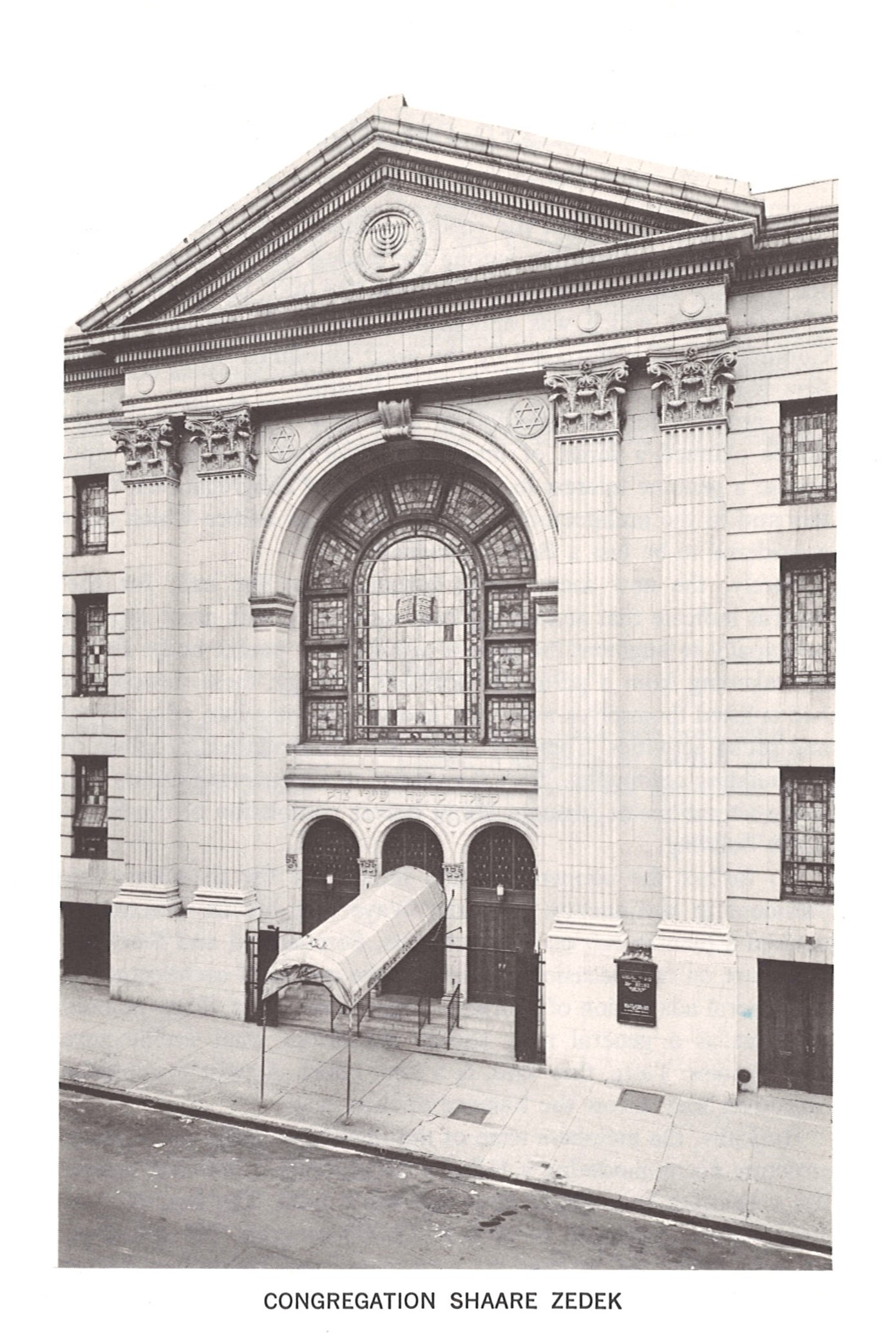

The architectural firm of Sommerfeld and Steckler was tasked with designing the new edifice on 93rd Street. William C. Sommerfeld and Benjamin Steckler were both established architects in their own right, having respective practices in New York around the 1890s, but in 1906 they merged to establish the firm of Sommerfeld and Steckler. They built a variety of structures and styles, however, flats and tenement buildings were among their most common. Their decision to design a synagogue in 1922 was a different direction for the firm; however, the resulting design assured them of their capabilities amongst the architectural elite (LPC, 1990, p. A138). The synagogue was dedicated on April 15, 1923.

‘Arguments and frustrations were many’ regarding this decision but the congregation ultimately decided upon a $300,000 three-story structure with a large auditorium and balcony.

Structure and Design

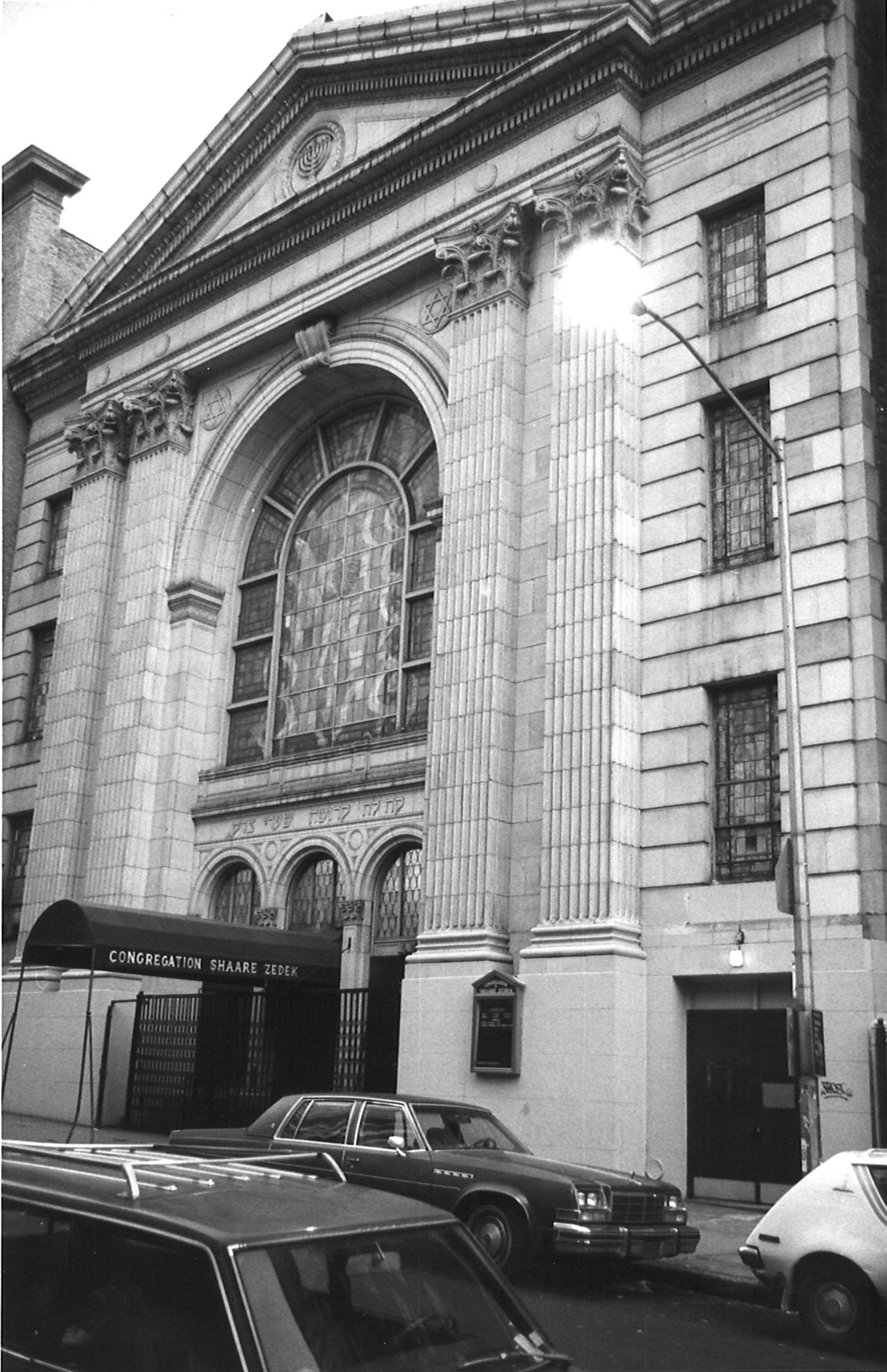

The synagogue was situated on the interior of the city block surrounded by residential and commercial buildings, a common feature for these later synagogues established on the Upper West Side as many of the corner plots were taken decades previous. The imposing Neoclassical stone structure featured four-story Corinthian columns flanking the center of the synagogue drawing attention to the entryway marked by three arched openings. Above the first story was an enormous arched window of divided-lite stained glass reaching up to the pediment which spans the building.

There was clear reference applied by the architects to the previous places of worship on Henry Street and 118th Street and Lenox Avenue. The congregation acquired 38 and 40 Henry Street in 1850. Originally built by a Quaker group, the Religious Society of Friends, in 1828, it was converted to a synagogue in 1840 when Congregation Anshe Chesed bought the building for their own place of worship (Dunlap, 2004, p. 260). Shaare Zedek built a new synagogue with architects Flemer & Koehler in its place in 1891 (Real Estate Record & Guide, 1891A p. 145). The synagogue in Harlem, designed by Schnieder & Herter, is unique for its Moorish Revival style but retains a familiarity with the landscape of European and American synagogue-type construction with its featured two towers above the roofline (Gruber, 2012).

The most notable common threads between all three buildings are the tripartite arched entryway, the large central arched or circular stained glass windows, and divided-lite windows that stretch 2-3 stories in height above double doors to the east and the west of the facade.

History on the Upper West Side

The congregation achieved a major move to establish a permanent home and reconciliation within the community and in the decade after the synagogue was established, much activity occurred within the congregation. The congregation’s success was recorded by a growth in numbers, appointing a new Rabbi, Dr. Elias Solomon, paying off their mortgage, and holding several fundraisers. Prosperity in these years was chalked up to a golden age of American society, but also due to the frugality of the congregation. Minutes from board meetings showcase the conservative attitude of the congregation at the time withholding from big ventures after many changes in the congregation.

However, this frugality wouldn’t last as they began to develop their education and social outreach. Additionally, this change collided with the oncoming of the Great Depression marking the end of this period of good luck and prosperity, ‘the land of abundance for a decade was in a deep declining spiral’ (p. 100). Archival records show the leadership attempted to save face and offer words of confidence and assurance in the face of adversity with rising costs and foreclosures all around them. The minutes of board meetings in 1931-32 revealed the manifestation of the congregation’s financial troubles with staff members’ wages on a steep decline during this period. Social and educational ventures suffered in tandem with this.

Around the mid-1930s membership and funding began to pick up steadily and in 1944 the congregation paid their mortgage on 212 West 93rd Street in full.

Struggles of the Congregation

As evident from the various recorded meetings, debt was always something that followed Shaare Zedek around. With the debt of their synagogue paid off, a little over 20 years after they purchased it, and membership increasing, the congregation was excited about the future. However, they faced ongoing financial hardship with their cemetery in Bayside, Queens, purchased in 1865. Debts surrounding ownership and upkeep of the cemetery continued to haunt the congregation for many decades, but beginning in the mid-20th century, the cemetery was vandalized in a series of anti-Semitic attacks (New York Times, Feb. 19, 1951, New York Times, May 13, 1971, New York Times, Dec. 18, 1973, New York Times, Aug. 27, 1976).

The congregation fell on hard times in the 1970s and 1980s, and with financial troubles, a dwindling number of congregants, and a small staff, the cemetery suffered. By the 1980s, congregants protested that the congregation was “essentially defunct” with no rabbi and irregular services and the cemetery fell into such a state of disrepair that it has struggled to recover ever since. Many Jewish families began to migrate to the suburbs during this period leading to smaller and smaller memberships and ultimately funds earmarked for cemetery upkeep were diverted to subsidize the synagogue’s faltering budget. ‘Most observers familiar with the situation say it is in worse condition than virtually any other Jewish cemetery in the New York area’ (Jewish Telegraph Agency, Oct. 18, 2002).

Debts surrounding ownership and upkeep of the cemetery continued to haunt the congregation for many decades, but beginning in the mid-20th century, the cemetery was vandalized in a series of anti-Semitic attacks.

Shaare Zedek bounced back in the 1990s with a new merger and a young and charismatic rabbi – but the congregation couldn’t seem to get back on its feet permanently. They believed their 95-year-old building was the sole asset that would relieve them of their debts and in 2016, the congregation entered into discussions with developers to build a 14-story condominium in place of the Neoclassical synagogue. It would house a place to worship and a discretional space for the congregation in the basement. Although a submission for landmark consideration was submitted to the LPC by concerned neighbors and advocacy groups, the historic building was never designated and was ultimately demolished.

This familiar threat is affecting religious institutions across the city. Congregations facing dwindling attendance and shrinking donations look for other sources of revenue and increasingly they turn to their most valued asset; their historic building (and in some cases the air above them).

References:

Congregation Shaare Zedek (2023). sznyc.org

Dunlap, D. (2004). Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide to Manhattan’s Houses of Worship. Columbia University Press

Gruber, S. (2012) ‘Samuel Gruber’s Jewish Art & Monuments’. http://samgrubersjewishartmonuments.blogspot.com/2012/12/usa-new-yorks-moorish-masters.html

‘The Jewish Cemetery Nobody Wants’, Jewish Telegraph Agency, Oct. 18, 2002

Landmarks Preservation Commission (1990). ‘Upper West Side/Central Park West Historic District Designation Report’.

Monsky, J. (1964). Within the Gates. Congregation Shaare Zedek.

‘Vandals in Cemeteries’, New York Times, Feb. 19, 1951

‘Queens Synagogue Damaged by Fire’, New York Times, May 13, 1971

Vandalism Is On The Increase in City’s Cemeteries’, New York Times, Dec. 18, 1973

‘Suspect…Arrested in Thefts of Bronze Doors From Cemetery’, New York Times, Aug. 27, 1976

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Research & Preservation Director of LANDMARK WEST!