Congregation Ansche Chesed

824-830 West End Avenue

by Tom Miller

A faction of Congregation B’nai Jeshurun split away in 1829 to form its own congregation, Ansche Chesed (People of Kindness). They worshiped in rented rooms until 1842 when the old Quaker Meeting House at 38 Henry Street was purchased and converted to a synagogue. Within a decade the congregation grew to be the largest in America.

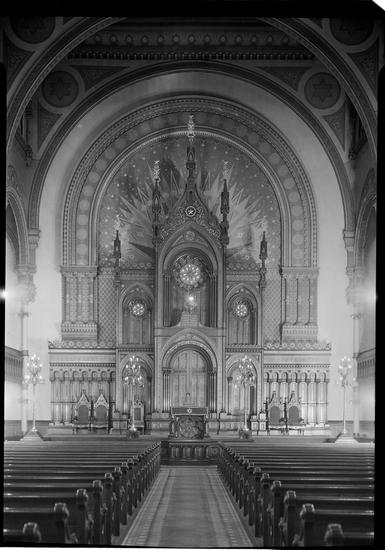

In 1872 the congregation erected a striking synagogue on Lexington Avenue, designed by D. & J. Jardine. There would be two more moves. In 1908 the congregation built a neo-Classical temple at 114th Street and Seventh Avenue, and in 1926 hired architect Edward I. Shire to design its final home, at the corner of West End Avenue and 100th Street.

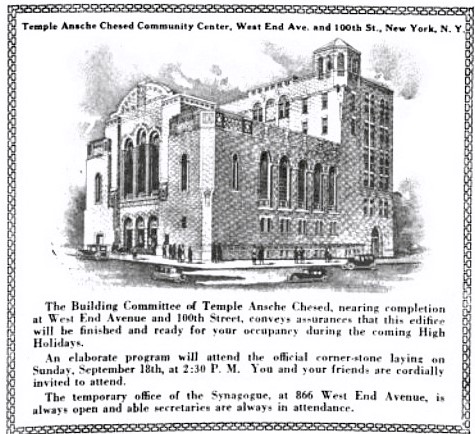

An advertisement in The Jewish Tribune on August 26, 1927 promised, “the Building Committee of Temple Ansche Chesed, nearing completion at West End Avenue and 100th Street, conveys assurances that this edifice will be finished and ready for your occupancy during the coming High Holidays. An elaborate program will attend the official corner-stone laying.”

That ceremony was held on September 18, 1927 with, according to The New York Times, about 1,000 people in attendance. The article placed construction costs of the synagogue and adjoining five-story “educational and social centre” at $1.2 million (closer to $21.1 million in 2024). It described Shire’s design as “an adaptation of the Romanesque and Byzantine styles, done in deep buff-colored brick and stone. It seats 1,600 persons.” In the abutting building on West 100th Street would hold “classrooms, a gymnasium and social hall seating 500, a small chapel and a roof garden.”

Limousines were parked out front. Top hats, striped pants and cutaway coats were de rigueur

The dedication of Temple Ansche Chesed took place on May 6, 1928. By then the construction costs had risen to $1.3 million. The Reform Advocate reported, “Nathan Straus lighted the ‘eternal light’ hanging above the ‘ark’ as 1,000 members and friends of the congregation devoutly stood in silence.” The new synagogue was among the wealthiest and most prominent in the city. Calling Ansche Chesed “one of the grand synagogues of the Upper West Side,” decades later, The New York Times journalist Douglas Martin would recall, “Limousines were parked out front. Top hats, striped pants and cutaway coats were de rigueur.”

The social hall was quickly put into use and on May 9, 1928, The New York Times reported that the Center players of Temple Ansche Chesed had performed Jubilee as part of a series of plays written by prison inmates.

On November 29, 1934, former Ambassador to Germany James W. Gerard addressed the congregation, and, perhaps, tried to assuage some of their worst fears. While describing Germany as the “greatest troublemaker” among nations, he added, “In the last few days, however, I have intuitively felt that there may be a speedier end to Hitler’s rule than I previously thought would be possible.”

The congregants had good reason to be fearful. Four months earlier, on July 21, anti-Semitic vandals broke into the synagogue. The New York Times reported that they “destroyed several hundred prayer books, damaged praying shawls and a dozen or more pews with knives and saws and left a typewritten note threatening to burn down the synagogue.” In a ransacked office on the second floor, detectives found a note that read, “Listen, you damn Jews. If you don’t get more money in this place, I’ll burn it down. The Mechal.”

Around 1940, the congregation hired 25-year-old Elvin Nichols, a Baptist, as a porter. The black man had just arrived in town from Richmond, Virginia to tend to his ailing mother. He made $35 a week cleaning and such. As the years passed, Elvin learned traditions and religious protocols, like arranging the sacred books for the holidays. By the 1950s, the temple’s membership had dwindled as more and more congregants moved to the suburbs. The New York Times remarked, “By the mid-70’s plaster had crumbled from walls, floors had buckled from water damage and the congregation was down to 60 families.” But Elvin Nichols stayed on, sometimes going unpaid for weeks.

Each Sabbath, Nichols stood at the temple doors, greeting the worshipers with “gut shabbos,” or “good sabbath.” In the worst of times, the loyal porter “was often the only one around to draft burial certificates or scour the Saturday streets for a tenth Jew—the minimum for a minyan—to say nothing of holding intact the plumbing and lighting,” said The Times. In 1977, Nichols was mugged in the synagogue’s lobby. He lost most of his teeth in the attack.

After four decades of service, Elvin Nichols retired in 1988. Douglas Martin of The New York Times reported on October 19, “On Sunday afternoon came the time to honor Mr. Nichols, and more than 200 people turned out, a standing-room-only crowd.” State Attorney General Robert Abrams was there, and Mayor Ed Koch sent a letter “proposing a toast.”

By the mid-70’s plaster had crumbled from walls, floors had buckled from water damage and the congregation was down to 60 families

Music was a major part in the culture of Congregation Ansche Chesed. On March 22, 1970, for instance, a “Cantorial Concert” was held here. The daylong Hanukkah Arts Festival on December 18, 1981 culminated with Peter Yarrow of the Peter, Paul and Mary folk trio and Martha Schlamme, cabaret and folk singer, performing. Two years later, the Hanukkah Arts Festival featured “a concert of Sephardic music by a group called Voice of the Turtle,” as reported by The Times. Beginning in 1988, the Brooklyn Lyric Opera performed in Hirsch Hall within the community house. It opened with Bizet’s Carmen on January 7. The group staged its operas at least through 1991.

By the early years of the 21st century, Congregation Ansche Chesed offered a wide variety of programs. The 2007 If You’re Thinking of Living In…noted, “Participants in its many adult programs need not be Jewish.” Among the offerings were several preschool and nursery programs, and a small homeless shelter. The programs continue today. The shul’s website mentions that the members “learn together during Ansche Chesed’s many classes, talks and scholar in-residence programs…and work together to improve our world through social action programs.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Be a part of history!

Stay local to support the nonprofit currently at 824-830 West End Avenue: