Central Baptist Church

649 Amsterdam Avenue

by Tom Miller

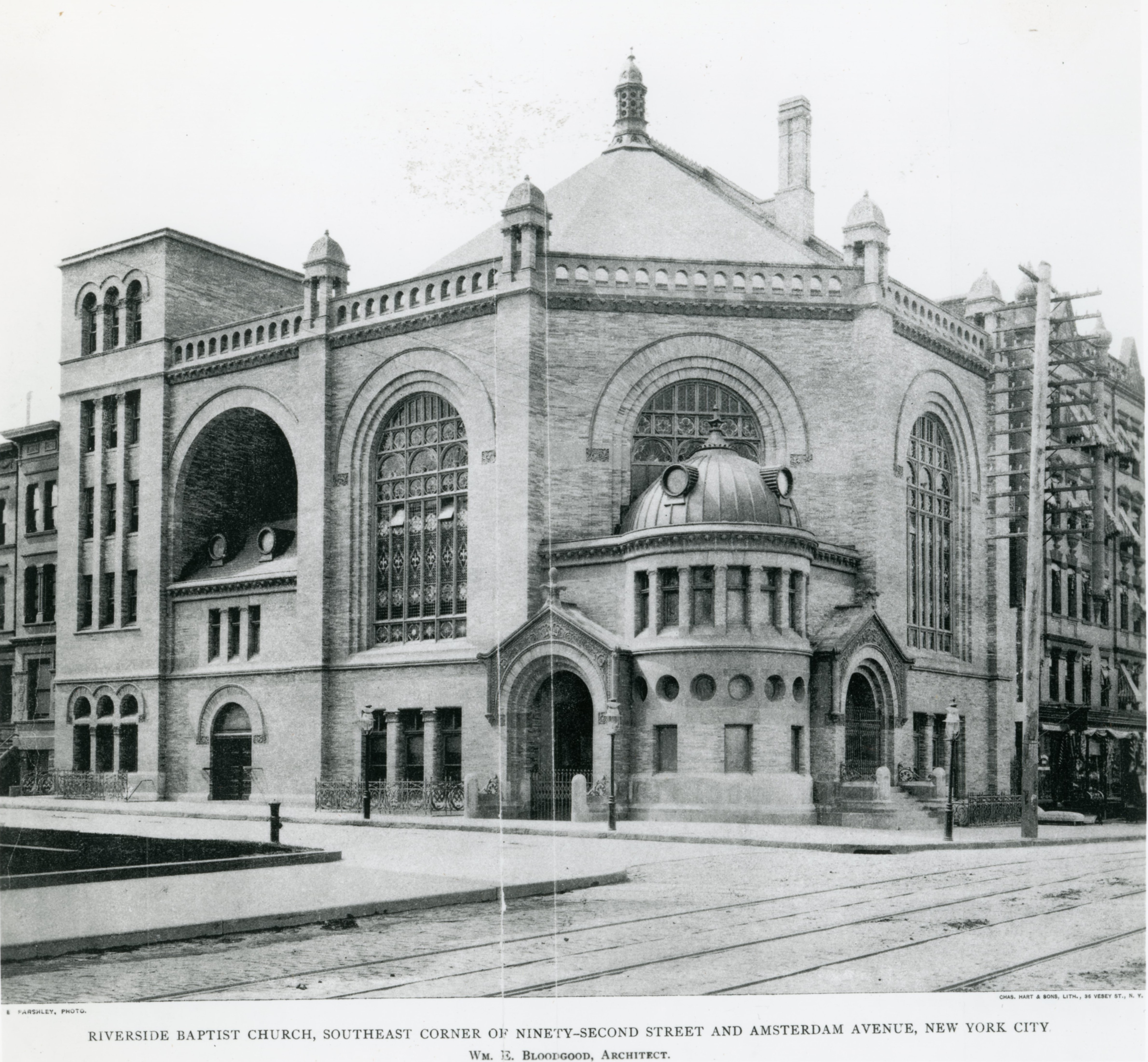

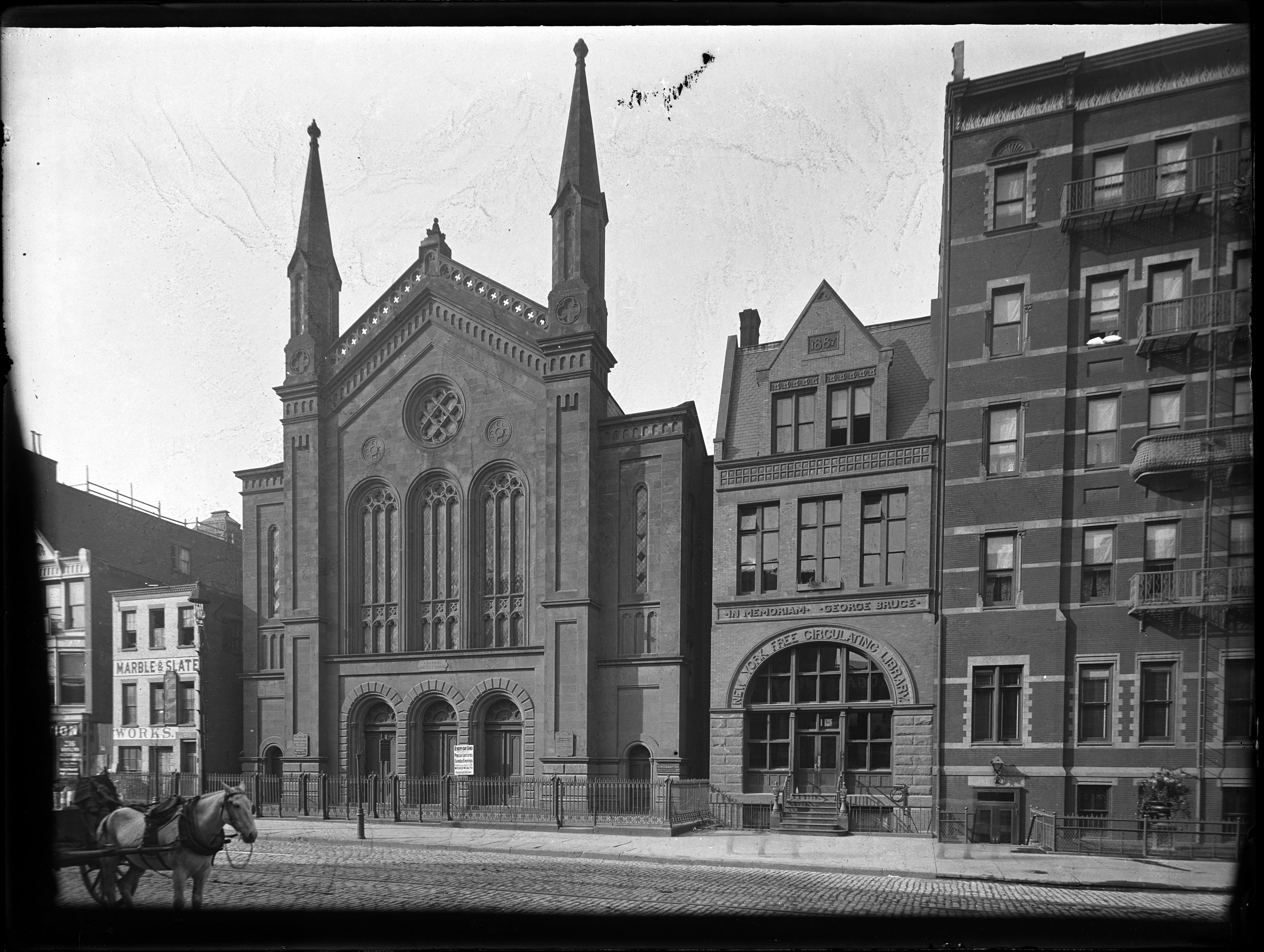

As early as 1898, Central Baptist Church, located on West 42nd Street near Broadway, was closely affiliated with the West Park Baptist Church (also known as Riverside Baptist Church) at 92nd Street and Amsterdam Avenue. That year Central Baptist’s Embroidery Class and its Carpentry and Chair Caning Class were held at the uptown location. The relationship would become even closer a decade later. Central Baptist was an outgrowth of the 1842 Laight Street Baptist Church. When the congregation erected its handsome church at 220 West 42nd Street, the Longacre Square district was the center of the carriage-making industry, its side streets lined with brownstone homes. The New York Times remarked in 1911, “It was one of the first Baptist churches to be built in the upper part of New York, which at that time was considered a suburb of the city.” However, at the time of that article, Longacre Square had been renamed Times Square and was the center of Manhattan’s theater district.

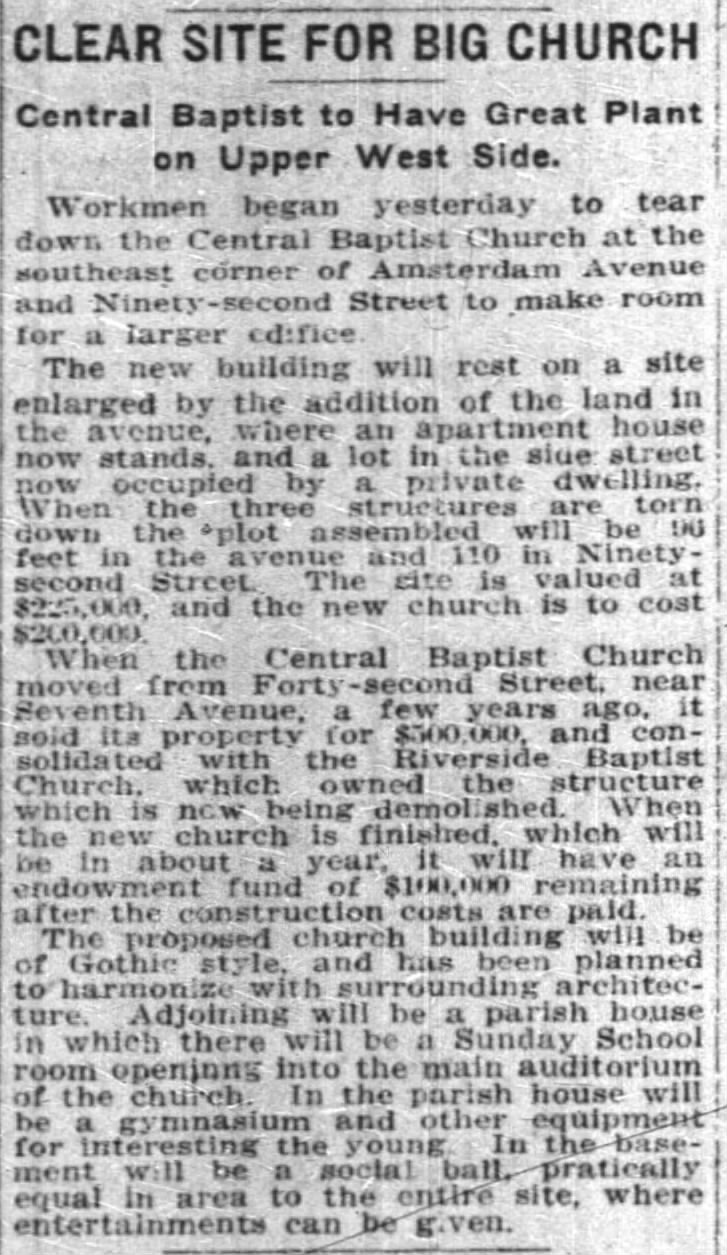

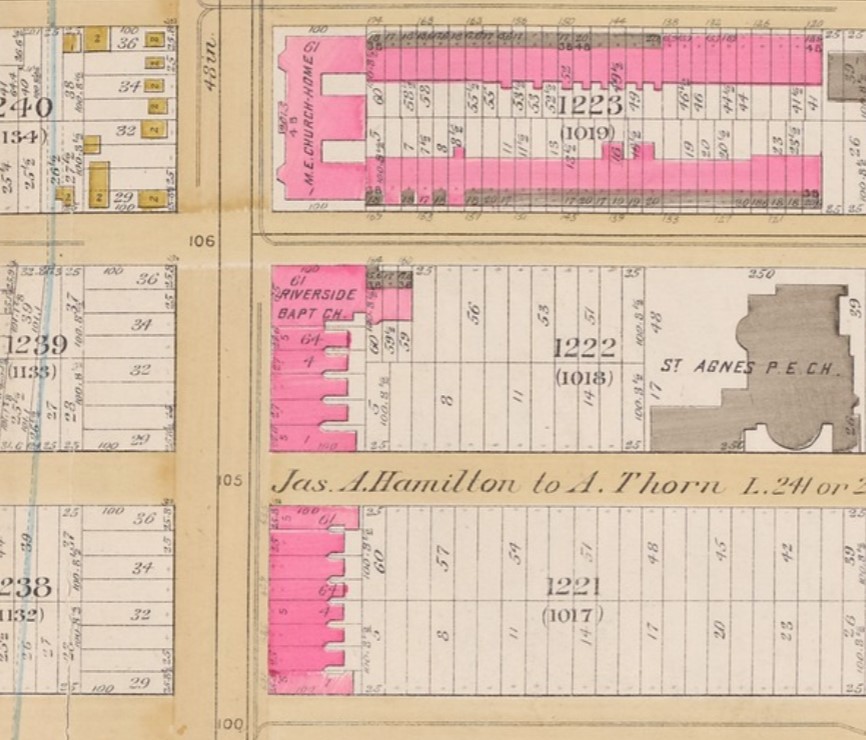

On March 29, 1910, The New York Times reported that “The changed conditions in the Times Square district led the officers of the Central Baptist Church to contemplate moving to a more residential locality.” The article said that the West Park Baptist Church had been authorized by the State Supreme Court “to transfer the church property on the southeast corner of Amsterdam Avenue and Ninety-second Street to the Central Baptist Church of West Forty-second Street.” The two congregations had merged and “a new Central Baptist Church will be organized.”

Services continued in both locations until October 1911 at which time The Sun reported that the theatrical firm of Frazee & Lederer and P. Chauncey Anderson had purchased the vintage 42nd Street church as the site of a theater for $500,000–a substantial $14.7 million today. It later became the Candler Theatre, then the Sam H. Harris Theatre. The article noted that the old West Park Church was also for sale. “When this is disposed of a new edifice that will accommodate both congregations will be erected in the neighborhood of the uptown church.”

But the Central Baptist Church trustees decided not to sell the Amsterdam Avenue structure, but to replace it. On March 2, 1912, the New York Globe reported that the congregation intended to build “a splendid new edifice” which would be “one more important, influential church added to the residential section of New York’s upper west side.” Architects Walter Cook and Edward F. Pallme were hired to design the structure.

The plans, filed in June 1915, placed the cost of construction at $200,000. The Real Estate Record & Guide noted it would be 78 feet wide on Amsterdam Avenue, and stretch back 115 feet on 92nd Street. “The building will contain accommodations for a Sunday school and parish house. The church auditorium will seat approximately 1,000 people.” (That left little room for increasing membership, which was currently at 700.)

The New-York Tribune reported, “Simplicity is to be the feature of the exterior, and utility of the interior.” The article noted, “So extensive is the Central’s new enterprises that it is not expected to complete it before September, 1916.”

The congregation intended to build “a splendid new edifice” which would be “one more important, influential church added to the residential section of New York’s upper west side.”

Demolition of the old church along with a house on 92nd Street began on August 1, 1915. Nine months later, on May 6, the cornerstone was laid “with a simple service of hymns and Scripture readings by the Rev. Dr. Frank M. Goodchild, the pastor,” according to The New York Times. Inside the box were the church’s yearbook and annual report, a history of the Baptist Church, newspapers, 1916 coins, and such. With World War I raging in Europe, Dr. Goodchild commented, “Let us hope that when this stone is removed and this box taken out a hundred years from today there will be peace on earth and accord of nations.” It was an optimistic wish.

Completed in 1917, Central Baptist Church was designed in “the modified English Gothic order.” Built of Germantown stone (a type of granite) and Indiana limestone, a corner tower, 118 ft. high, dominated the design.

Although the New-York Tribune had promised that the interior would be designed with utility in mind, the stained glass windows, by Gorham Studios, were by no means utilitarian. The New York Globe, on October 6, 1917, said “But the glory of the auditorium is the great west window, thirty-eight feet in height by twenty-two feet wide. It consists of seven panels in three groups…and the whole is of such marvelous depth and splendor of color as is impossible to describe.” Gorham Studios also designed the ten side windows which depicted scenes of the Life of Christ.

The Rev. Dr. Frank Marsden Goodchild had been pastor of Central Baptist Church since 1895. It was he who recognized the need to relocate the church immediately upon taking the pulpit. Seemingly indefatigable, he wrote three religious books, was a “visiting preacher,” and was president of the American and Foreign Bible Society, president of the Ministers’ Home Society, and vice president of the Baptist Union for Ministerial Education.

As the church rose, he got into a heated confrontation with U. S. Army General Frederick Funston for the latter’s “attitude toward the activities of clergymen in the army.” Goodchild insisted that clergymen be permitted “to preach without restrictions to soldiers,” while the general demanded that preachers “must not tell the soldiers that they were lost and were in need of being saved.” He added that he did not “wish the emotions of the soldiers stirred and wanted no such thing as a revival,” said The New York Times on November 21, 1916. From the pulpit, Dr. Goodchild called Funston a “religious dictator” and demanded that Congress investigate conditions in the army.” The well-publicized feud prompted other Baptist ministers to distance themselves from the fiery pastor.

Goodchild’s health began to fail in 1923. That year he and his wife sailed to France for six months “in the hope that the long vacation would restore his health,” said The New York Times. Instead, upon his return he suffered a stroke. He preached his farewell sermon on January 6, 1924, during which he dedicated the life of his six-month-old grandson, Robert Marsden Goodchild, “to the Christian life, and to the Christian ministry, if God so wills.” (He presumably did not consult his infant grandson on the decision.) In tribute to his long service to the church, the congregation gave him cash equal to a year-and-a-half’s salary. Goodchild died on February 18, 1928.

Dr. Goodchild was replaced by the Rev. Dr. John Falconer Fraser, who, in 1931, also found himself in a heated confrontation. In his sermon on November 1, he declared that the name of the Central Baptist Church had been dragged “into scandalous notoriety by the reckless villainy operating in the name of the United States Government.” The previous week the church had been named as co-defendant in a “padlock suit” for running a speakeasy disguised as a bird store on West 91st Street.

Falconer told his congregants that he was not used to speaking about political issues from the pulpit, but “It seems incumbent on your minister to make a statement on this unseemly subject.” He insisted the church had no connection with the owners of that building nor the shop and said, “God knows, the speakeasies stoop low enough in their practices in evading the law, but it is doubtful if they an equal the latest publicity stunt of the Federal authorities in New York City.”

As the decades passed, the neighborhood, the congregation, and the church’s outreach changed. The youth of the neighborhood caught the attention of Richard “Pee Wee” Kirkland in 1994, who began the School of Skillz basketball camp at Central Baptist Church every Saturday.

Kirkland was born in Harlem in 1945 and learned basketball on the streets. A sensation in high school and college, he was drafted by the Chicago Bulls in 1969, but he turned down the offer, presumably because he was making more money as a drug dealer, money launderer, and jewel thief on the streets. He was arrested in 1971 and sent to the Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary in Pennsylvania on a ten-year sentence.

He told The New York Times journalist Vincent M. Mallozzi in January 1997, “Thirty years ago, I was part of the problem. Thirty years later, I’m part of the solution.” The solution included mentoring young Upper West Side boys through basketball. He said that while in prison he thought of the people who had wanted to see him go into the N.B.A. “I knew the only way to repay those people was to one day work with kids, because somewhere out there there’s another Pee Wee Kirkland, and until that kid turns his life around, I will always feel his pain.” Kirkland ran his School of Skillz at Central Baptist Church for years.

The previous week the church had been named as co-defendant in a “padlock suit” for running a speakeasy disguised as a bird store on West 91st Street

In the summer of 1997, Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani created a task force to examine the relations between the city residents and the New York City Police Department. It followed the beating and torture of Abner Louima in a Brooklyn precinct station house. Among the members was Central Baptist Church minister Rev. Michel Faulkner. He called the group “the most diverse task force in the history of New York City,” saying the members “poured their heart and soul into a process that they truly believed in.”

Faulker was crestfallen when, a year later, Giuliani essentially dismissed the task force’s findings, saying “the panel had failed to recognize the department’s recent success in reducing crime.” Of the task force’s recommendations, he said “Some of the things we’ve already done. Some of the things I’ve opposed in the past, I’ll continue to oppose them. And some of the things are unrealistic and make very little sense.”

The uneasy relationship between Faulker and Giuliani continued. In March 2000, an unarmed Black man, Patrick M. Dorismond, was shot dead by police. Three months later Giuliani had still not expressed condolences to the victim’s family. On June 3, Elisabeth Bumiller, writing in The New York Times, reported, “He has not reached out to Representative Charles B. Rangel of Harlem…or to former allies like the Rev. Calvin O. Butts and the Rev. Michel Faulkner.” Faulkner told Bumiller, “I’ve sent him a couple of messages. I haven’t heard back from him. I don’t know what it means, to be honest with you. To me, it’s not good.”

The Central Baptist Church continues to serve a noticeably dwindling congregation. And while the handsome 1917 structure with its stunning stained glass windows is little changed, with no landmark protection, the sale and destruction of the church is a constant threat.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Be a part of history!

Stay local to support the nonprofit currently at 649 Amsterdam Avenue ake 166 West 92nd Street: