2028-2032 Broadway – The Ormonde

by Tom Miller

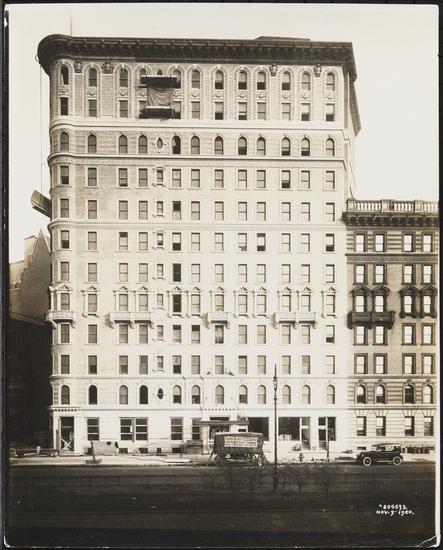

Architect Robert Maynicke was best known for designing loft buildings, many of them along lower Fifth Avenue. However, in 1899, he received a commission from developer James Butler for a 10-story residential hotel on the southeast corner of Broadway and 70th Street. The slant of Broadway gave the site an irregular, nearly triangular shape. Completed the following year, Maynicke’s neo-Renaissance style structure was clad in beige brick above the ground floor. The upper floors were embellished with Renaissance-inspired elements like stone balconies, Scamozzi columns that upheld classical pediments, and heraldic shields.

While almost all apartment buildings on main thoroughfares had their residential entrances tucked away on the quieter side streets, the Ormonde was, somewhat surprisingly, entered on Broadway between retail shops. After passing through a vestibule, the visitor entered an entrance hall and reception hall, described by The Engineering Record on January 20, 1900 as “being practically one.” Here, said the article, “rugs and seats for the comfort of the visitor are grouped about a hearth at one side.” The article noted, “The halls have mosaic floors, marble wainscot and tinted walls.”

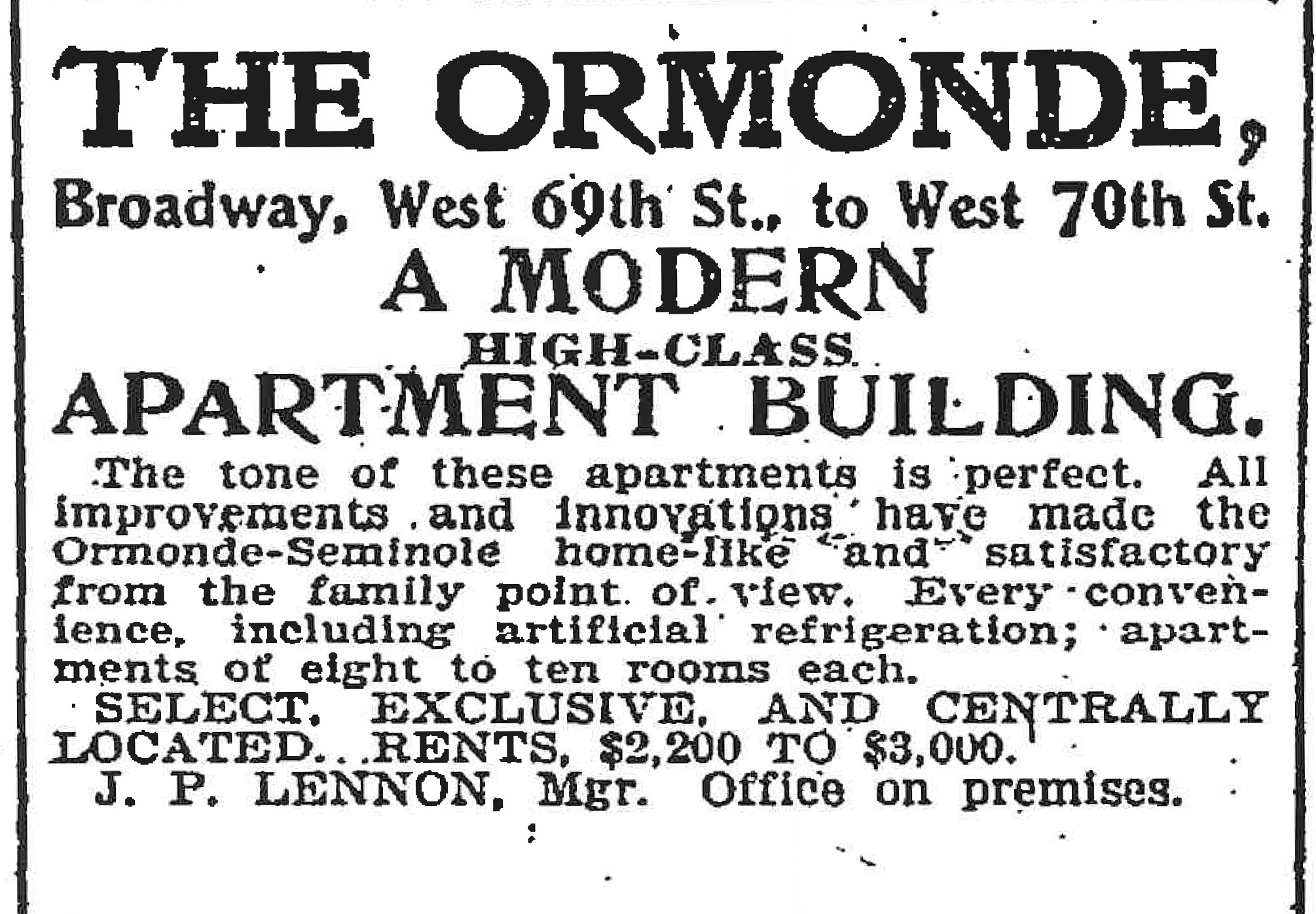

The Ormonde had three apartments per floor of eight, nine, or ten rooms. Rents ranged from $2,200 to $3,000 per year—about $9,000 per month for the most expensive by 2024 terms. Residents of the ten-room apartment had a dedicated elevator, accessed by a long, arched hallway with a stained-glass ceiling. Apartments were nearly equal to a private house. The Engineering Record said each had “a parlor, a library and a dining room, a kitchen, a butler’s pantry and a servant’s room, together with a main bathroom and a bathroom opening from the servant’s room.” All dining rooms and parlors (and some bedrooms) had fireplaces.

Gas ranges and refrigerators cooled from a plant in the basement eliminated the need “for handling coal and ashes or for having ice brought into the building.”

The Ormonde featured both gas and electric lights. “Push buttons for lighting and extinguishing the lights are provided in all the rooms,” said The Engineering Record, “and each apartment is fully equipped with an annunciator system ringing in the kitchen.” Gas ranges and refrigerators cooled from a plant in the basement eliminated the need “for handling coal and ashes or for having ice brought into the building.” Another modern amenity was the telephone provided to each apartment. Residents did not need to worry about sharing an elevator with staff or deliverymen. Separate service elevators opened into the service areas of each apartment.

Perhaps the best-known resident in the first years of the 20th century was theater manager and producer Charles Frohman. Known for his ability to develop stars, he discovered talents like Ethel Barrymore, Billie Burke, Julia Marlow, and John Drew, Jr. In 1896, he co-founded the Theatrical Syndicate, a booking network throughout the United States that monopolized theatrical bookings and contracts until the Shubert Brothers broke into the business prior to World War I.

Despite the Imperial German Embassy placing warnings in newspapers against sailing overseas in April 1915, Frohman boarded the RMS Lusitania and headed to Liverpool on May 1, 1915. Six days later, a German U-boat fired a torpedo into the luxury liner, sinking it and killing 1,199 innocent civilians, among them Charles Frohman. On May 14, the New-York Tribune reported that Frohman’s body was due to arrive in New York on May 23. The article said there would be a private service at Frohman’s apartment, followed by a public service at the Temple Emanu-El.

In 1919 James Butler hired architect William H. Gompert to gut-renovate and enlarge the Ormonde, transforming it from an apartment building to a residential and transient hotel. In its February 1920 issue, The Edison Monthly reported that the massive renovation was nearing completion. “It involves removing practically the entire interior partitions and equipment,” said the article, “leaving only the floors and exterior walls.” Two seamlessly matching stories were simultaneously added. “The new Hotel Ormonde will have an entrance on Broadway and another on 70th Street, both of which will lead into a large, handsome foyer.” Part of the second floor was removed to create a double-height desk area. The article explained:

The building when completed will contain some three hundred bed rooms and almost as many baths. It will also include all the essential and principal rooms incidental to a modern hotel, such as large dining rooms, grills, barber shops, manicure parlors and other rooms and spaces for the convenience of the guests.

Perhaps to avoid confusion, Butler opened the gut-renovated building as the Hotel Embassy. The official opening was marked with a dinner for 300 guests on January 8, 1921. “The dinner was followed by a dance which lasted until midnight,” reported The New York Times. The proprietor J. C. La Vin, who owned a farm in Orlando, Florida, had a surprise for the female guests. “Each of the 150 present received a silver jewel case containing a live alligator, eight weeks old,” said the article.

An advertisement described the Hotel Embassy as “New York’s newest hotel, absolutely fireproof, 350 rooms, all with bath.” In the hotel’s Restaurant Francais, the “Business Men’s Luncheon” cost $1—about $14.50 in 2024 terms. Dinner patrons would enjoy dancing “from 10 p.m. to closing.”

Among the hotel’s first and arguably most prestigious guests was Princess Catherine Radziwell of Russia. The manager, Robert R. Maffitt, cautiously investigated “the Princess’s antecedents and had found her to be entitled to the royal prefix,” reported the New York Herald on October 30, 1921. When Princess Radziwell fell behind in her rent, she explained that “she expected money from her London bankers.” Eventually, the titled guest was asked to leave.

When Princess Radziwell was subsequently sued by the Hotel Shelburne in Coney Island for $352.52 board and lodging, Robert Maffitt testified. The New-York Tribune noted, “Her bill at the Hotel Embassy was considerably larger than the amount she is said to owe at the Shelburne.”

Among the hotel’s first and arguably most prestigious guests was Princess Catherine Radziwell of Russia.

Items of clothing and other valuables began disappearing from guests’ rooms in the summer of 1926. Suspicions turned to a maid, Anna Slaby, when her references and address turned out to be fictitious. Four days after the wife of Gustav Guggenheim, the vice president and general manager of the Chatham Burlap Bag Corporation of Savannah, Georgia, complained that clothing was missing from her rooms on August 4, Slaby was arrested. The New York Times reported, “According to detectives, the interior of the maid’s room looked like a modiste shop, with gowns and slippers hung up in the closets.”

The Hotel Embassy was lost in foreclosure in 1935. In the last quarter of the century, it was converted to an SRO, and its floors were divided into a warren of sleeping rooms. Things quickly devolved within the once elegant structure.

On November 15, 1975, The New York Times reported that employee John Ochoa ordered Robert Rodgriguez, who had been loitering around the lobby, to leave. When he did not, Ochoa fatally shot him. The article said Ochoa “fled after the shooting and then returned hours later for work at the hotel, where he also lived.”

Two months later, on January 24, 1976, two residents, Earl Sangster and Andrew Hancock, got into an argument. Hancock pulled out a firearm and murdered Sangster. The following year, on August 21, resident Nelson J. Ortiz attempted to break up a knife fight and was stabbed in the heart. Within the first six months of 1978, 13 fires were set in the Hotel Embassy.

On August 12, 1979, The New York Times reported that the building was “undergoing its third transformation in its 80-year history.” The article said it would emerge “as a 176-unit apartment house with studio apartments going for $450 a month and one-bedroom rents starting at $625 a month.” Once again called The Ormonde, the building received yet another renovation in 2017, including what a realtor described as “a Grand Marble Lobby with floating marble stairs.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business at 2028-2032 Broadway:

Meet Freddy Marcos and

Nathan Janovich!