160 West 71st Street – Hotel Alamac

by Tom Miller

On November 15, 1923, The New York Times reported on a dinner for 350 guests to mark the opening of the Alamac Hotel at the southeast corner of Broadway and 71st Street. The structure had been designed by Maynicke & Franke for the George Dose Engineering Co. The event, held at 11:00 the previous evening, was described as “a feast of the nations,” in eight courses. The article said,

The first course was American and the others in order were Scotch, Spanish, English, Italian, Russian, French and Turkish. Vaudeville acts by players of each country with its national music were presented as the diners progressed from one national food to another.

The main dining room on the ground floor where the banquet was held, was decorated in the Adam style. There were three other dining rooms in the building, the Japanese grill on the second floor; the Medieval Grill Room “which is finished in the style of the 15th Century,” according to Architecture & Building; and the Congo Room on the 20th floor. Architecture & Building described that restaurant—which included a dance floor—saying it would “appeal to those who crave an unusual and garish setting for their meals.” Guests entered off the elevator into a “reception room” with grass flooring and a straw-covered ceiling. After walking through the jaws of a gigantic idol mask, patrons were in a setting meant to evoke an African village.

“Booths representative of straw thatched huts flank the walls and the orchestra is housed in a native council chamber,” said the article. “The mural decoration [executed by Winald Reis] is bold in design and vivid in color, and the general lighting is from fixtures suspended from the ceiling representative of idol masks of bizarre design.”

Gimbel Brothers decorated the suites, paying close attention to the needs of long-term residents.

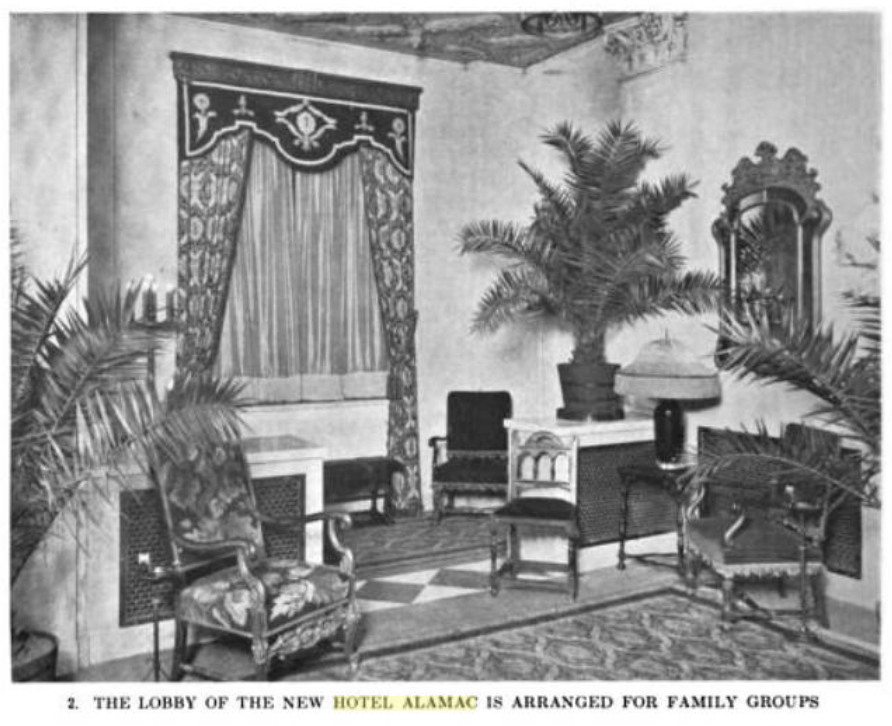

The other public areas were also designed in geographical or historic themes. The lobby was Renaissance in style with an elaborate plaster ceiling and marble flooring. On the second floor was a Japanese parlor. “The furniture is of the heavily carved dragon pattern,” said Architecture & Building. “There are Buddhas, war masks, bronze elephants and vases used for ornament.”

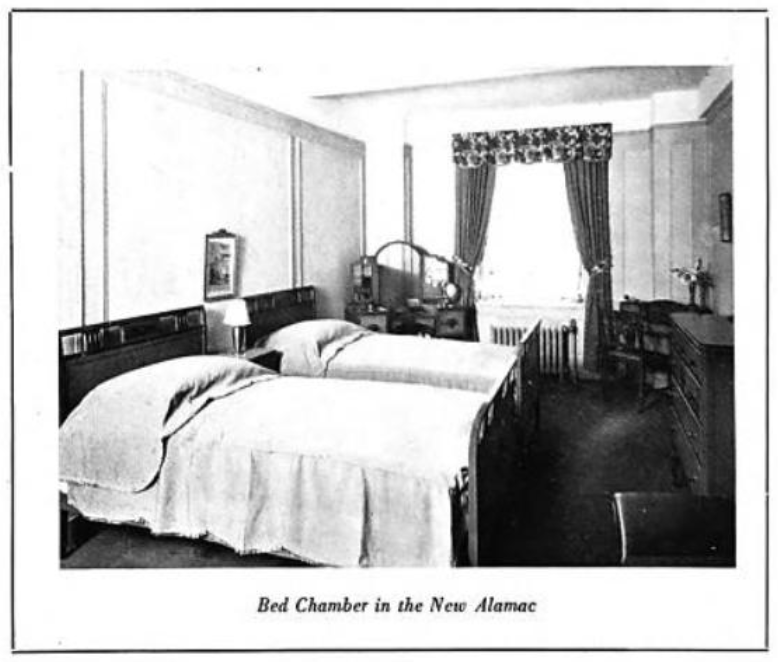

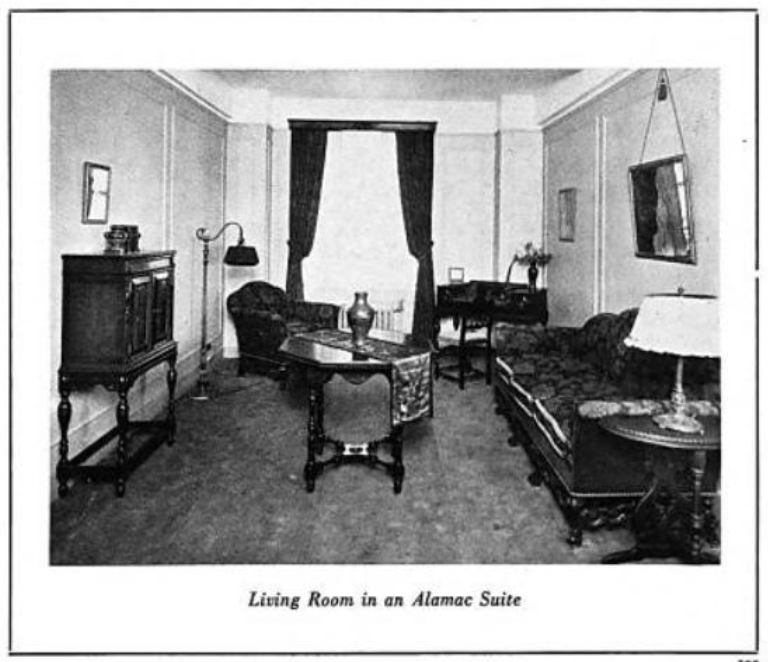

Within the Alamac Hotel’s 20 floors were apartments for both permanent and transient guests—the latter having just one room each. The apartments were furnished in historic styles—Early English, Chippendale, Queen Anne, Tudor, Sheraton, Colonial and William and Mary, according to The Furniture Index in December 1923. Gimbel Brothers decorated the suites, paying close attention to the needs of long-term residents.

The Furniture Index pointed out, “Magazines, newspapers, books which every family wants in its suite, have always given a hotel room a cluttered-up look. Gimbel’s avoided this by providing magazine racks and book ends for the convenience of their guests.” Other unexpected amenities in a residential hotel were a tie rack, whisk broom and shoe rack on the back of the bedroom closet door, and in the living room closet was a folding bridge table and two folding chairs.

The Hotel Alamac immediately became the annual venue for the New York International Chess Masters’ tournament. Following the tournament in April 1924, the American Chess Bulletin reported on the banquet held here. The article said in part, “A Chess Knight, sculptured in ice by the Alamac’s famous chef, gigantic Queens, Rooks and Bishops, imposing shields and bright-colored flags of all the countries represented in the tournament made the banquet…a never-to-be-forgotten spectacle.”

The glowing press coverage of the Alamac Hotel was marred in May 1924 by a horrific assault. The wife of playwright Howard Johnson met Harry Lasser and his wife in March that year at a party. The New York Times said Lasser “is a familiar figure in cabarets and cafes in the neighborhood of Times Square and upper Broadway.” On May 12, just before noon, the Lassers telephone Mrs. Johnson and asked her to have lunch with them. She met them in the dining room of the Alamac Hotel, where the couple was registered, and afterward she invited the Lassers to join her in an automobile ride.

The New York Times reported, “The party returned to the hotel in the afternoon and went to the suite occupied by the couple. Mrs. Johnson accepted their invitation to stay with them and have dinner.” While she and Mrs. Lasser were refreshing themselves after the automobile ride, Harry Lasser made cocktails. A while later, while Mrs. Johnson was in the bathroom, Lasser suddenly broke in and strangled her with a piece of cord until she fainted. When she woke up two hours later, her feet were bound, and her jewelry was missing.

Lasser suddenly broke in and strangled her with a piece of cord until she fainted.

Mrs. Johnson managed to free her feet and notified the management. She was told the Lassers had left the hotel hours earlier. The woman was hysterical when taken to the West 68th Street Station house. “At first the detectives were unable to obtain any account of what had happened,” reported The New York Times, “but later, after Mrs. Johnson had been more fully revived, she was able to tell enough about the affair that every available detective in the precinct was put on the case.”

The following evening Harry Lasser (who was “also known as Phillips, Roth, Drent and Behan”) was arrested in an apartment on West 48th Street. Mrs. Johnson positively identified him. As it turned out, she was lucky in losing $9,000 in jewelry and not her life. Lasser was wanted for the murders of Dorothy King and Louise Lawson, who were robbed in a similar fashion and killed.

In the third quarter of the 20th century the Alamac Hotel was purchased by The Brodsky Organization and converted to the Lincoln Square Apartments. It was the scene of an unsettling incident on December 12, 1985. At 4:10 that afternoon, 22-year-old police officer Jonathan Cobin responded to a report of a “disturbed man.” When he knocked on the door of Manuel Garcia’s room, he was shot in the hand through the door.

Police arrived with hostage negotiators and relatives of the gunman who tried to persuade him to surrender. The siege tied up traffic for an hour after police closed 71st Street between Broadway and Columbus Avenue. Finally, a robot was brought in to break into the apartment. Police found the 22-year-old Garcia dead on the bathroom floor. The rifle he used to kill himself lay next to him.

Although Maynicke & Franke’s colorful 1923 interiors are gone, the building is little changed outwardly after just over a century.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 160 West 71st Street aka 2054-2062 Broadway: