131-139 Columbus Avenue

by Tom Miller

In 1885, James Flanagan purchased the vacant lot at the northwest corner of Ninth (later Columbus) Avenue and West 66th Street for a staggering $68,500—about $2.25 million in 2024. Within a few years, real estate developer A. Jacob had acquired the adjoining plots to the south. The two men obviously worked together on their ensuing projects because on the same day, April 23, 1892, Flanagan’s and Jacob’s architects, J. Munkowitz and Edward Wenz, respectively, filed plans for five-story “brick flats.” All three buildings would cost $35,000 to construct. The two architects also worked closely together and the three resultant buildings were identical.

Each four bays wide, they held stores at the sidewalk level, one on either side of the residential entrances. Their two-story middle and top sections were separated by a projecting bandcourse. Brick piers, each capped with terra cotta capitals on the third and fifth floors, defined each structure.

The residents were middle class. Typical was Irish-born James Kennedy, who lived at 131 Columbus Avenue in 1893. A night watchman at the construction site of the Hotel Casa Alameda at 65th Street and Columbus Avenue, he was described by The Evening World as “a strapping young fellow.” Kennedy found himself in a difficult position at around 2:30 on the morning of July 12, 1893. While he was patrolling the site, three men, J. J. McKenna, his brother-in-law William Michels, and Thomas Conway, approached him “and began a tirade of abuse,” according to Kennedy later. He said the three were “hilariously drunk” and that McKenna (whom he recognized as a Central Park police officer when on duty) “called him the vilest of names.” Suddenly, the other two began to kick and pound him “without provocation.”

Kennedy “told his story in a straight-forward manner that carried the conviction of truth.

The fit Irishman paid little attention to McKenna’s cohorts, telling a judge later, “They were too drunk to do much damage.” He focused on McKenna, whom he “gave a good thrashing.” When Kennedy saw another cop coming down the avenue, he fled, fearing that within a minute, there would be “half a dozen bluecoats hunting for me.” He hid in the unfinished hotel until things calmed down. At 5:30, he went to the 68th Street stationhouse to explain himself.

McKenna was already there and “still under the influence of liquor,” according to The Evening World. He accused Kennedy of attacking him, and his two associates backed him up, saying, “Kennedy walked up to McKenna, who was sitting in a chair in front of the saloon, and assaulted the policeman.” When Kennedy began to tell his side of the story, McKenna drew his revolver, which was quickly taken away from him. McKenna was not done, however. “Then he pulled out a big knife that looked like a dirk and made a jab at my neck,” Kenney later related. That weapon, too, was taken away, and McKenna was locked up. The Evening World reported that Kennedy “told his story in a straight-forward manner that carried the conviction of truth. McKenna will probably have to answer to the Park Commissioners of his indiscretion.”

At the time, the two commercial spaces in 131 Columbus Avenue were home to New Schaffer & Coons, gas fitters; and real estate brokers and developers James M. and William R. Stewart. Both tenants would remain for several years.

The corner store was home to W. B. Parkin & Co.’s pharmacy. On April 13, 1903, The New York Times reported, “A lively blaze occurred at 11 o’clock last night.” Benjamin Goldstein, a clerk, had just closed up and was locking the front door when “there was an explosion behind the prescription counter, and a flame shot out and curled around the store.” Goldstein bravely ran back into the store to rescue the books. The article said, “He had hardly got them out when there was a second explosion, which cracked the heavy plate glass windows in the front of the store and scattered bottles all over the place.”

The occupants of the apartment buildings left “in some confusion, but without panic.” Happily, the firefighters extinguished the fire before it spread to the upper floors. Damage to the drugstore was estimated at about $71,000 in today’s money.

William F. Crane lived at 131 Columbus in 1900, the year that J. W. Farrington took over the real estate office formerly occupied by James and William Stewart. It bothered them that the triangular island between Broadway and Columbus Avenue directly in front of the building was unnamed. On July 20, 1900, they signed a petition to the Board of Alderman. It said in part that they “would respectfully suggest the name of Colonial square as a proper and suitable designation thereof.” They did not get their wish. It was named Empire Park North until 2017, when it became Richard Tucker Park.

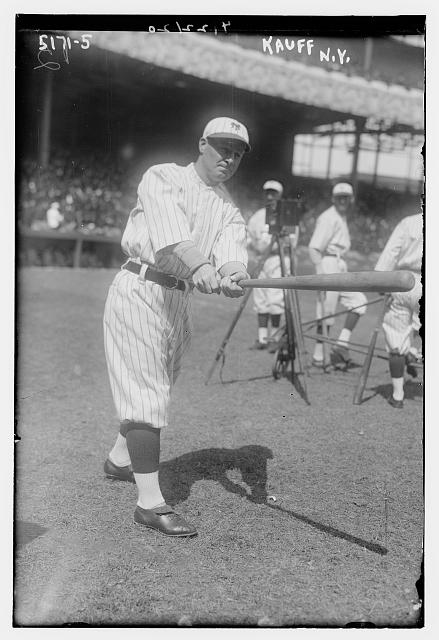

Kauff was known as the “Ty Cobb of the Feds.”

In the first years after World War I, Benny Kauff, the star center fielder for the New York Giants, opened an automobile accessories business at 135 Columbus Avenue. Kauff was known as the “Ty Cobb of the Feds.” Just how he came by the auto parts, however, was more than shady. Kauff also owned a body shop. He took orders for certain automobiles, sent his cronies out with the list, and then repainted the stolen vehicles in his shop. Parts that could be sold separately made their way to his Columbus Avenue shop. In 1919, Kauff was arrested after his cohorts stole the brand new automobile of James Brennan and were caught. He was banned from baseball despite being acquitted of the Brennan theft. (He testified he had been eating dinner with his wife at the time of the crime.) Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Landis said the acquittal “smelled to high heaven.”

In 1942, with Prohibition over, Irish-born John Phelan obtained a liquor license for Phelan’s Bar & Grill at 133 Columbus Avenue. Then, in 1950, all three buildings were converted to Single Room Occupancy. They survived until 1973, to be replaced by the 36-story residential building 2 Lincoln Square.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business at 131-139 Columbus Avenue: