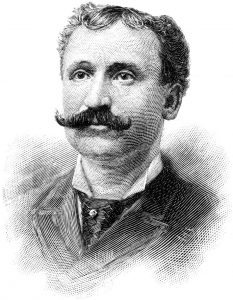

Carlo Barsotti, ca. 1890

By Claudie Benjamin

Christopher Columbus may have his statue up in the middle of Columbus Circle, but he is a myth, not a hero. The real man, as all school children have come to know, was horrific in many ways. Earlier generations were taught admiringly and erroneously, “he discovered America” and established that the world was round rather than flat.

A multitude of statues have been placed throughout the US, universities and schools have been named for him, along with rivers, neighborhoods and, yes, even avenues.

Today, Columbus is certainly part of the discussion in the controversy about giving prominence to people guilty of what would now be considered crimes against humanity. Should this figure be standing on a pedestal so prominently at the busy 59th thoroughfare? While Google measures from City Hall, traditionally, the Circle is the point from which all official city distances are measured.

The answer is that the hero here is not Columbus, but Carlo Barsotti, banker and publisher of the Italian American newspaper il Progresso. He is the man who orchestrated collecting the funds to construct the Columbus monument in 1892, marking the 400th anniversary of the infamous voyage. His motivation was unequivocal. He was proposing a significant way to acknowledge and honor Italian American immigrants’ contributions to their new country. This was in the face of widespread anger among Italian Americans of the time about the abusive working conditions and poor pay they were receiving for work on massive projects like the Croton Reservoir System bringing fresh water to NYC.

Barsotti ingeniously used his platform as a newspaper owner to convince small business owners as well as individual contributors to subscribe to the successful effort to fund the monument completed by sculptor Gaetano Russo in 1892.

Barsotti’s great skill in raising funds to fulfill this purpose in the form of public art resulted in the Columbus Monument and four other NYC monuments in NYC that honor Italians: Giuseppe Garibaldi (1888) in Washington Square, Giuseppe Verdi (1906) in Verdi Square, and Giovanni da Verrazano (1909) in Battery Park and Dante in Dante Park (1921).

More than 100 years later, the passionate support of the cause to spare the statues removal or destruction was shared by former Governor Andrew Cuomo, who, himself is of Italian heritage. The monument gained protection under the State Register and Barsotti’s legacy remains intact. Over time there has been criticism that rather than depicting immigrants, Barsotti’s commissions drew attention to high art like the opera in the Verdi statue, or the Italian icon of literature Dante, but overall there seems to have been acceptance of these works of art in the spirit Barsotti intended.

The Columbus Column stands 74′ tall. Since the time it was erected numerous changes have occurred in the immediate landscape. Originally, surrounding space was called the Grand Circle; to the East it was partly surrounded by the 59th entry to Central Park to the South and West a variety of Victorian buildings, early 2oth century commercial buildings were built and later replaced by more contemporary renovations and high-rise buildings. Oddly, the circle was broken by North-South traffic lanes for a period of years during the mid-20th Century, until the circle was restored. Fountains have been built at the base of the monument and then reconfigured to allow for more seating. One bold proposal that never happened was the brainchild of architect Edward Durell Stone, who designed the original 2 Columbus Circle. That building that faced the Circle and was commissioned by A&P supermarket heir Huntington Hartford as a museum to house his personal art collection (1964-69). Following major alteration and renovation in the early 2000s, the building has since been occupied by the Museum of Art and Design.

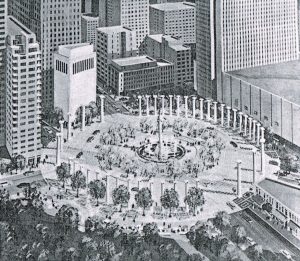

Stone’s proposed ReUse of the Pennsylvania Station columns, ca. 1960

A 1960s sketch of Stone’s proposal shows the monument in the middle of a vast circle ringed by columns. This would have been a repurposing of 24 of the 84 35′ Roman Doric Columns by American Sculptor Adolph Weinman created for Pennsylvania Station and removed when the building was razed. The project that at the time, would have cost $750K, but did not receive the necessary support. Many of the columns were simply dumped in the Meadowlands of New Jersey.

Decades later in 2012, another artistic expression was realized as a striking temporary three-month Public Art Fund-commissioned exhibit by the Japanese artist Tatzu Nishi. His construction was of a furnished penthouse “tower” apartment. Visitors climbed stairs or went by elevator to enter, putting attendees up close and personal with the larger-than-life figure of Columbus. Typically, Nishi seeks to provoke a viewer’s thoughts – in simulating an encounter with Columbus in an upscale apartment with park views, he is perhaps raising the question – who are actually our heroes and why and how do we honor them?