263 West 86th Street

Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church

300-302 West 91st Street, aka 633-635 West End Avenue

by Tom Miller

An elegant and technologically advanced church

The Rev. Joseph R. Kerr sparked a major rift within his congregation in 1892. Pastor of the Fourth Presbyterian Church, he pushed to relocate the church to the rapidly developing Upper West Side. The New York Times later explained “One faction, of which Dr. Kerr was the head, was anxious for the removal, while another, to which some of the most influential members of the church belong, felt that the removal was unnecessary and beyond the resources of the church. Dr. Kerr’s faction, however, carried the day, and the new church, one of the most pretentious on the west side, was built.”

Founded as the First Associate Presbyterian Church in 1785, the renamed Fourth Presbyterian had already moved four times before settling at No. 160 West 34th Street in 1867. Now, in April 1892, the church purchased five building lots at the southwest corner of West End Avenue and 91st Street from John Curry and Thomas Cochrane for a staggering $65,000.

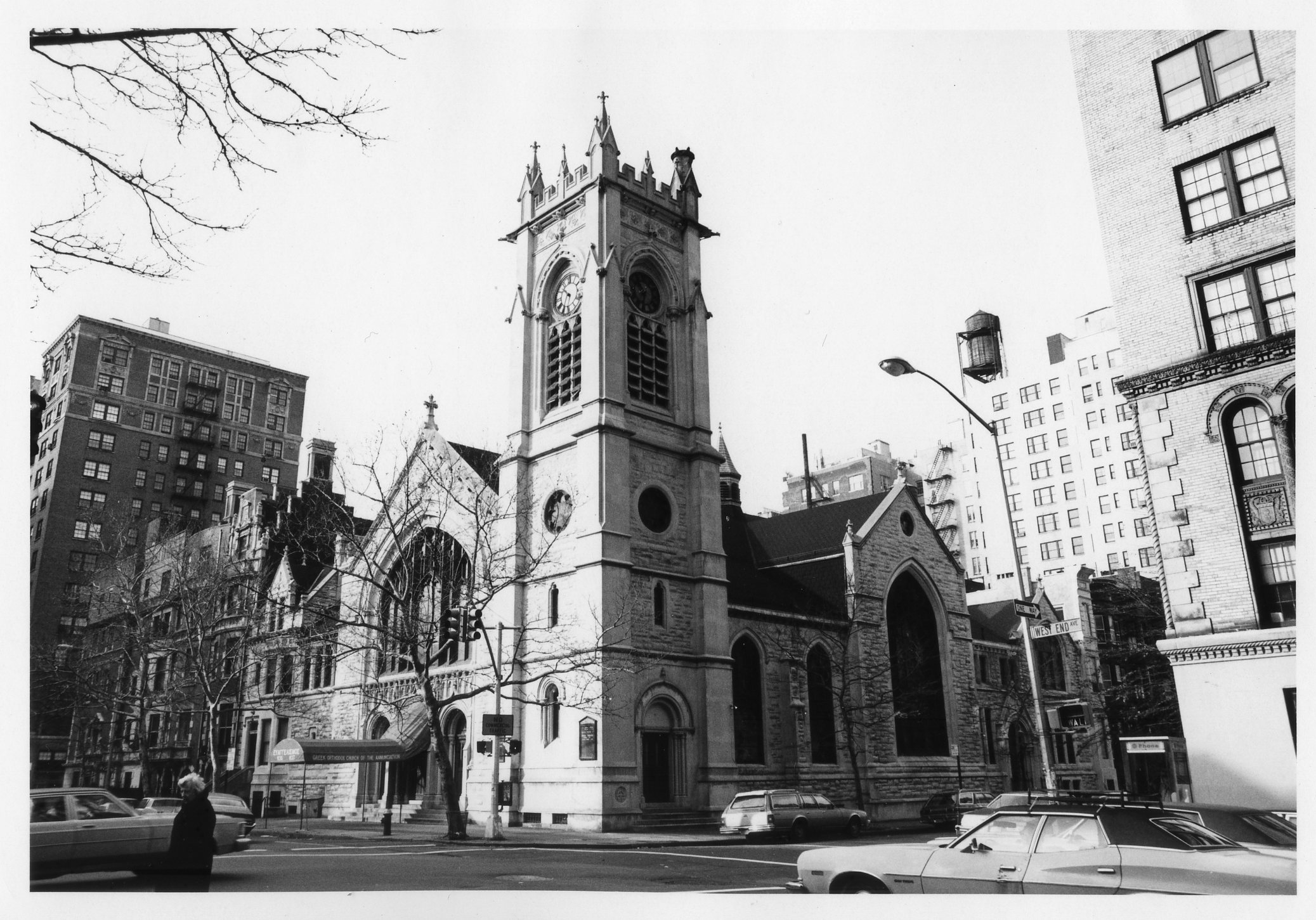

The immediate area was essentially undeveloped–a situation which would rapidly change. Before the decade was out handsome rowhouses would line the blocks around the site. On May 7, 1892 the Record & Guide announced “The Fourth Presbyterian Church will build a fine church edifice.” Plans were filed in January 1893. The trustees had hired architects Heins & LaFarge to design the structure. Just four years earlier George Heins and Christopher Grant LaFarge had begun work on the monumental Cathedral of St. John the Divine. This new commission, while certainly minor in comparison, was nonetheless noteworthy.

The architects designed a low structure of rough-faced limestone melding Norman and Gothic elements. On January 31, 1893 The New York Times reported “The church will have a square tower on the corner. The front entrance will be triple, and over these doors will be large mullioned windows…These high, narrow windows, extending from the top of the arched doorways almost to the roof, will be the most notable feature of the whole front.” Indeed the massive arch containing stained glass windows above the entrance nearly filled the upper portion of the West End Avenue facade. The 91st Street elevation received a similar treatment. The New York Times noted “These windows are considered the flower of the construction, since their form is essentially stately and decorative by day and specially suited for effective illumination at night.”

The clock-and-bell tower at the corner had been scaled down, as explained by The Times. “The plans, as prepared by the architects, provided for a lofty spire, which it was decided to omit, and finish the tower with corner pinnacles.” Instead of a spire, the 60-foot tower culminated in those spiky pinnacles, a crenelated parapet, and picturesque gargoyle waterspouts. The projected cost of the new structure was $115,000, bringing the total expenditure to what would be around $4.8 million in 2016. Those congregants who had worried that it would be “beyond the resources of the church,” would rest more easily when the 34th Street property was sold for $200,000.

With about 200 members present, the cornerstone was laid on June 10, 1893. Possible problems between the trustees and the architects may have been exposed when the trustees went with a different firm to design the rectory. A month earlier plans for “a parsonage or ‘manse’ for the Fourth Presbyterian Church, on West End avenue,” were filed by Jardine, Kent & Jardine, as reported in the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide on May 13. In describing the new church building on March 24 1894, the day before its dedication, the New-York Tribune pointed out the modern technology of the clock tower. “The electric clock in the tower is a novelty, self-winding, self-illuminating, and regulated from the National Observatory at Washington.”

The newspaper described the interior as being “in quartered oak and chestnut, with olive upholstering. The pews on the main floor are arranged in a semicircle. The gallery is boxed, and also chaired for single sittings. The organ is made by Farrand & Votey, and promises to give every satisfaction, both in appearance and quality.”

There was also a chapel, accessed on 91st Street. On the second floor were a “handsomely furnished” lecture room, parlors and committee rooms. The day after the dedication The New York Times noted “The pulpit and pulpit steps are beautifully carved. Above the pulpit, at the back, are windows which will be illuminated at night by gas and electric lights.” Because electricity at the time was unreliable the lighting fixtures of Fourth Presbyterian were designed with gas back-up. “The great central chandelier has 114 gas burners and 107 incandescent electric lights,” said The Times. In the basement were the kitchens and space for a proposed gymnasium.

In describing the new church building on March 24, 1894, the day before its dedication, the New-York Tribune pointed out the modern technology of the clock tower. “The electric clock in the tower is a novelty, self-winding, self-illuminating, and regulated from the National Observatory at Washington.”

A quick succession of pastors

Members who had opposed Rev. Kerr five years earlier got revenge of sorts in 1897. Trouble started when the pastor began missing the Wednesday night prayer meetings in the fall of that year. Trustees “came to the conclusion that there must be something wrong with Dr. Kerr’s private life,” according to The Times a few months later. They hired a private detective to tail the minister. The detectives followed Kerr for several weeks. A telegram from Kerr arrived at the rectory on the afternoon of Wednesday, November 9 saying “because of an important engagement down town” he would not be able to get home. A member of the church session also received a telegram, informing him that Kerr would not be able to lead the prayer meeting that night.

Almost simultaneously, the detectives sent word to church officers for an immediate meeting. The investigators took three trustees and an elder to a Broadway hotel. Telling a bellboy that they needed to get into a room to make repairs on a gas fixture, they burst in. “Dr. Kerr was found in the company of a young woman,” reported The Times.

The minister “pleaded for clemency, but the Trustees were obdurate and demanded his resignation.” The scandal was briefly kept quiet, even after Kerr tendered his resignation on November 27. But it was quickly leaked and on December 4 Wallace D. Barkley, President of the Board of Trustees confirmed the rumors and added “the woman in the case was unmarried and employed in a Broadway store.”

There were some who said Rev. Kerr’s undoing was the result of his insistence on building the new church. One of the Trustees denounced the action to a reporter. “He said that the majority of the board felt that there was an animous [sic] against Dr. Kerr on account of his efforts to have the church removed up town.” As it turned out, the scandal not only cost Kerr the pulpit of Fourth Presbyterian but his ministry as a whole. On December 18 The Times reported, “The Presbytery of New York decided yesterday by a vote of 90 to 4 that the Rev. J. R. Kerr, D. D., be deposed from the Christian ministry and suspended from the communion of the Church.”

Fourth Presbyterian would see a quick succession of pastors. On May 14, 1899, the Rev. Dr. J. Wilbur Chapman took the position. He had been pastor of Bethany Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, making $6,000 a year plus “$1,100 more and three months’ time” off for evangelistic work. He took a 50 percent pay cut at Fourth Presbyterian, receiving $3,000, “and is to give up his outside evangelistic work, or almost all of it,” said The New York Times. “He does this because he is convinced of the importance of the work at the Fourth Church and of his own fitness to accomplish it.”

The newspaper explained, “he believes he can build up the up-town parish, and is going to bend all of his great energies to the task.” It clumped him among the modern businessman-type of pastors. “They are stout of person, jolly of manner, and maintain the unministerial mustache.”

As he promised, Chapman increased the congregation. When he took the pulpit there were about 100 members and an income of about $6,000. Within four years he increased the congregation to about 700 and the annual receipts were $50,000. But the lure of evangelical work was too strong. On October 26, 1902 he resigned noting, “My interest has long been in evangelical work, and I feel that administering that branch of the whole Presbyterian Church will be a splendid opportunity.”

Chapman’s successor was Chicago preacher Dr. Pleasant Hunter. He accepted the position on December 1; however a Chicago newspaper cautioned “He has a host of friends in Chicago who wish he might find it possible to stay here.” And like Chapman, the Rev. Dr. Hunter lasted only four years. “Many women in the congregation burst into tears when Dr. Hunter announced his intention of leaving,” reported the New-York Tribune on November 19, 1906. He had accepted the pastorate at the Second Presbyterian Church of Newark. While Chapman’s reason to leave was altruistic, Hunter’s was more self-serving. The Tribune pointed out that income would be $8,000 a year, “the largest paid to any minister in Newark.” The handsome salary would equate to about $217,000 in 2016.

Both men would be back at Fourth Presbyterian in October 1910 when the church celebrated its 125th Anniversary. The week-long event included sermons preached by eminent ministers. Chapman traveled from Europe to take part; and Rev. Hunter delivered his sermon on Sunday, October 16. The Rev. Dr. Edgar Whitaker Work was pastor at the time. He expanded the church’s offerings to include musical and instructional events. On April 18, 1912, for instance, The New York Observer reported that he “has commenced a series of services in his church, West End avenue, and Ninety-first street, under the general title ‘Evenings with Great Masters of Sacred Music.'” Classical works with religious themes were presented, including Mendelssohn’s Elijah, and Gounod’s Redemption.

Earlier that year the Hon. C. Irving Fisher, M.D., had presented a lecture on “The Panama Canal and the West Indies.” The New York Observer noted “The lecture was illustrated with lantern slides from photographs taken recently by Dr. Fisher while on his official inspection of the Canal Zone,” and added, “Mr. Fred Krimmling entertained the company with several vocal selections.” Before coming to Fourth Presbyterian, Rev. Work had been pastor of the Third Street Presbyterian Church in Dayton, Ohio. He was, therefore, especially moved when the Great Dayton Flood in March 1913 destroyed 20,000 homes, displaced 65,000 people and killed more than 360.

In pleading for donations from his congregation, Rev. Work read the response to his letter to Ohio Governor James M. Cox on March 30. In said, in part, “Great suffering and distress. It is estimated that we will be compelled to feed from 200,000 to 500,000 persons for two or three weeks in Ohio.” Fourth Presbyterian members responded with a special collection which was turned over to the relief fund for flood sufferers.

On October 26, 1902 he resigned noting, “My interest has long been in evangelical work, and I feel that administering that branch of the whole Presbyterian Church will be a splendid opportunity.”

Transition towards Orthodox tradition

In December 1918 the Rev. Dr. J. Wilbur Chapman was back in New York to be operated on for gallstones at the Dumas Sanatorium on West 74th Street. He died there of complications on Christmas Day. In reporting his death, the New-York Tribune estimated that more than 25 million people had heard him during his evangelistic career after leaving Fourth Presbyterian. The funeral of the world-famous evangelist was held at Fourth Presbyterian Church on Sunday, December 28.

On October 17, 1920, a bronze tablet was unveiled in memory of Dr. Chapman. Rev. Work, who was still pastor, had just returned to the pulpit after an illness of nearly a year. Fourth Presbyterian Church was the scene, of course, of notable weddings and funerals. One in particular drew the attention of New Yorkers. On May 1, 1940, Julia Ruth was married to Richard Wells Flanders here. It was the father of the bride who made the event so newsworthy.

Julia was the adopted daughter of George Herman Ruth. The Ruth family lived in the Ansonia residential hotel on Broadway between 73rd and 74th Streets. By the time of the wedding, Ruth had been retired for five years. But the celebrity of baseball player “Babe” Ruth had not diminished; nor has it to this day.

In 1952, the congregation of Fourth Presbyterian voted to merge with the Olmstead Avenue Presbyterian Church in the Bronx. Negotiations had begun to sell the West End Avenue building to the Greek Orthodox Church of the Annunciation, currently worshiping nearby on West End Avenue and 85th Street. The sale was formally closed on New Year’s Eve, 1953 with a purchase price of $250,000. Fourth Presbyterian held its final service on December 27 and on January 3, 1954, the Greek church moved its relics and icons into its new home. In Greek Orthodox tradition, the transition from the former church to the new one was marked by a procession. Leading the solemn cavalcade was the Icon of the Virgin Mary Theotokos.

In 1991, the parish initiated a $2.5 million restoration, which included the stained glass, masonry, and roof renovations, and restoration of the 1924 Skinner pipe organ. The project was spearheaded by architects Balamotis McAlpine Associates.

The private homes of the Upper West Side’s broad avenues were largely replaced by tall apartment buildings throughout the 20th century; but somehow the trend missed this block. The result is that Heins & LaFarge’s Fourth Presbyterian Church is visually undiminished and still commands the corner of a delightful slice of 19th-century New York.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com