A Home for Respectable, Aged and Indigent Females

by Tom Miller

In the early 19th century, women who were born to affluent families and who subsequently married “well” could expect lives of comfort in fine homes, catered to by servants. They could expect such things as long as their husbands survived.

Quite often a gentleman’s entire estate would pass to his eldest son while sometimes, but not always, allowing his wife to continue living in the house and using his carriage and horses. Just as often, the widow was left to the compassion of her family and creditors. Women who months before had worn silk dresses and attended the theatre in pearls found themselves essentially penniless.

In 1814, in response to the large amount of needy widows subsequent to the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, the Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females was founded. Many citizens found the entire concept unfounded. “The alms-house was thought to be the suitable provision for all those who must be supported by charity,” according to a later association report.

The group, however, persevered, endeavoring to promote the welfare of “those who have been born and bred under happier auspices, many accustomed to the refinement of affluence, and all of a class too respectable in their connections and associations in earlier life, and too worthy in themselves, to be the proper subjects of the common alms house.”

Women who months before had worn silk dresses and attended the theatre in pearls found themselves essentially penniless.

During its first year, the association provided charity to 150 aged females.

After two decades of visiting the deprived women in their homes, it became evident that a facility was necessary which could provide shelter as well as medical care. “Nothing short of an asylum where they could be wholly provided for…could meet the urgency of many cases,” an annual report recorded.

An Asylum was erected in 1838 that was capable of housing 93 “pensioners.” A long list of applicants were interviewed and should a woman be deemed acceptable she was required to wait until a vacancy was made available by the death of a current inmate. Applicants often waited a year or more before admission.

Treasurer, Mr. R. C. Anderson suggested in the annual report of 1852 the need for a larger facility. “The Asylum is now filled to its utmost capacity, and many well deserving and proper persons are anxiously waiting for admission, to whom this boon cannot be afforded at present.”

A plot for the new building was recommended at 78th Street and 4th Avenue and preliminary plans by Hurry & Rogers were drawn for a building that would accommodate 200 inmates. Financial backing for the building was not complete until 1865 and three years later plans by Richard Morris Hunt were “presented, discussed and decided upon.”

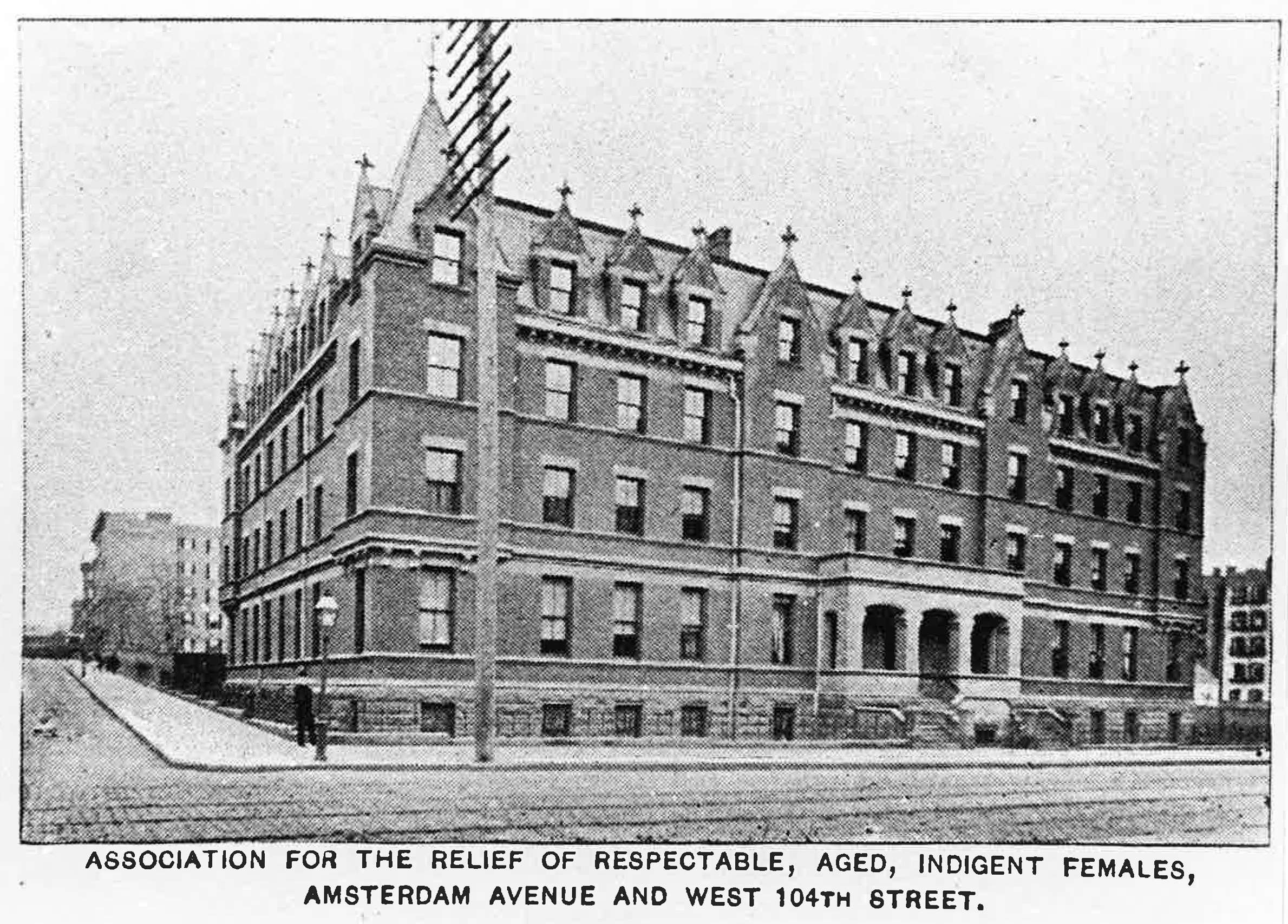

Not until 1881 was action finally taken, when land was purchased at 103rd Street and Amsterdam Avenue (then 10th Avenue) farther uptown where land was less expensive. In 1883, Hunt’s new building was complete; a massive brick and stone French Gothic pile with a cornice serrated by pointed dormers.

By 1907, the capacity of the building – no longer referred to as an asylum – was strained. Mrs. Russell Sage donated funds to enlarge the residence to the south, adding thirty rooms and a larger chapel. Architect Charles A. Rich was given the commission with instructions that the façade must be “in conformity with the present building and on the same lines.”

Completed a year later, the addition seamlessly mimicked Hunt’s original design. The two-story chapel with medieval buttresses and lancet arches featured windows by Tiffany Studios.

In June of that year, plans were announced for its demolition — of one of Hunt’s few surviving New York buildings — to be replaced by a modern nursing home.

The Association continued in the building through the 20th Century, remodeling in 1965 to meet new sanitary requirements. Problems arose in 1974, however, when the aging structure failed to meet fire safety codes. In June of that year, plans were announced for its demolition — of one of Hunt’s few surviving New York buildings — to be replaced by a modern nursing home. Local residents revolted to the news, calling it a “neighborhood landmark” that could be used by community groups as a “little city hall.” A $9 million loan was sought to save the building.

In 1990 a renovation was completed, resulting in New York City’s first youth hostel with “Manhattan’s largest privately owned” garden. Managed by Hostelling International NY, the mammoth structure successfully retains its Victorian outward appearance.

Approach the building at night and it is a scene from an Edward Gorey drawing – haunting and brooding. In the bright daylight, however, it is a delight of angles and peaks – a remarkable survivor of a bygone era.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Landmarks Timeline

EXPLORE HOUSES OF WORSHIP

Designation Report

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the nonprofits currently at 891 Amsterdam Avenue:

HI New York City Hostel

Learn about the ReUse of 891 Amsterdam Avenue