Gangsters and Showgirls–often Both!

by Tom Miller

By the mid-1920’s the rows of fashionable private residences that had lined West 72nd Street at the turn of the century were being replaced with commercial and modern residential buildings. In 1926 a group of investors, the 48-56 West 72nd Street Corp., hired the architectural firm of Sugarman & Berger to design a residential hotel on the former site of five high-stoop houses.

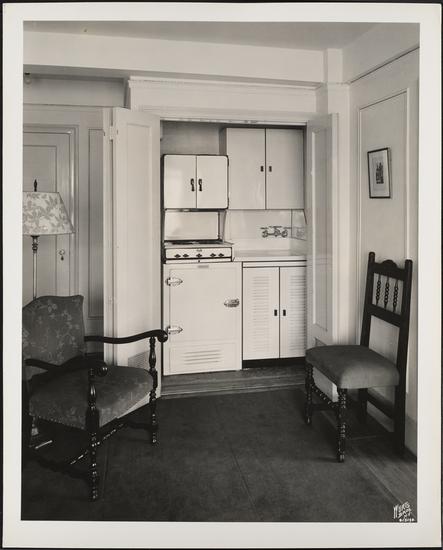

Residential hotels differed from apartment buildings in that they offered the services of a hotel—maid service, for instance—and did away with kitchens and dining rooms in the suites. Residents ate in a large restaurant-like dining room or had meals delivered to their rooms. The concept eliminated the need for most personal servants.

Called the Hotel Ogden, it was ready for occupancy in 1927. Sugarman & Berger’s 1920’s take on the Renaissance Revival style placed 15 stories clad in rough-faced brick upon a limestone base that held retail space. The second and third, and the top three floors, were given handsome terra cotta detailing in the form of elaborate pilasters, rows of shell-like corbels, and stylized shields within the tympani of the arches.

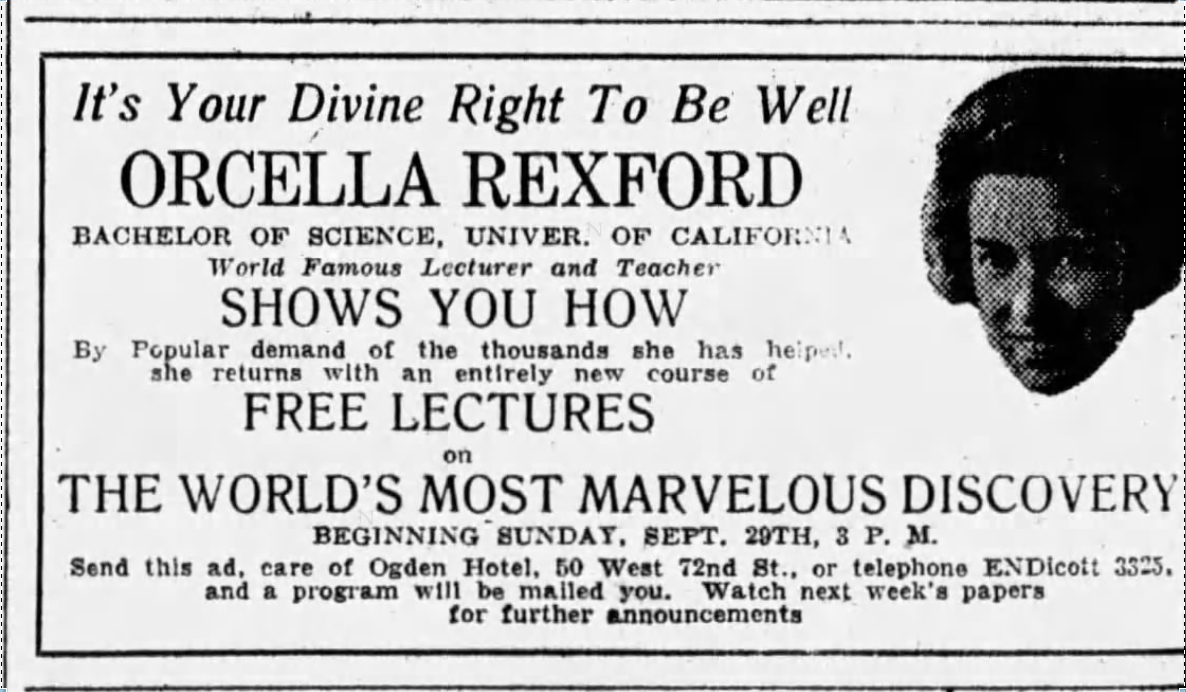

There were 209 apartments with a total of 330 rooms. Among the upscale amenities available to the tenants were the Stern’s Hotel Ogden Orchestra which played during the dinner hour (and was broadcast for an hour on the radio) and a roof top golf course. On September 10, 1928 the Jamestown Evening Journal wrote “Upon the roof of the Hotel Ogden, where one of the most elaborate roof courses is laid out, there are miniature reproductions of some of the famous golf spots in the world—replicas of a famous tee, of a certain famous hazard, a lake and all the rest.” It became a popular spot for “midnight golfing.” The article said “Brilliant arc lights stream across the course. Gents in evening suits menace the trim tailoring of their shoulders…Ladies in evening gowns and glistening jewels look out. Other gentlemen who have stopped in the ‘whoopee parlors’ for a few cocktails, grow boastful of their prowess, but find difficulty connecting with their ‘tee-off.’” (Prohibition would not end for several more years and a “whoopee parlor” was a speak-easy.)

“Upon the roof of the Hotel Ogden, where one of the most elaborate roof courses is laid out, there are miniature reproductions of some of the famous golf spots in the world—replicas of a famous tee, of a certain famous hazard, a lake and all the rest.”

Several of the residents of the Hotel Ogden were in the entertainment business. One was Annette Jenkins who had given up her career in motion pictures when she married aviator and engineer George Jenkins. She had not given up her close contacts in the field, however, and on Christmas Eve 1928 she drove motion picture promoter Harry Richards and his sister, Mrs. Lotta Groves, in her automobile to a Bronxville party.

Annette had to navigate through a snowstorm on their way back to New York City early that Christmas morning. She was headed to Greenwich Village to drop off her passengers when, at 10th Avenue and 49th Street, she ran down 55-year old William Coughlin. Perhaps in a panic, the 28-year old sped on, leaving Coughlin in the snow where he died. The driver of a milk wagon witnessed the accident and followed the car to Ninth Avenue and 38th Street where he found a policeman and had Annette arrested. She was found guilty of fleeing from a fatal accident in April 1929 with a potential prison term of three years.

A mysterious death occurred in the Hotel Ogden a few months later. Thomas Robbins, the captain of the bellhops, was found dead in a washroom. His body showed signs of trauma—a cut over the eye and bruising. But if there had been foul play, the other employees were not talking. “Some agreed on the story that Robbins had been injured while moving a trunk yesterday,” reported the Times Union. “In this manner they accounted for a cut over his eye. Others held that he was hurt when he ran against an elevator door.”

Chorus girl Flo Hart lived in the Hotel Ogden at the time. She had been married to the motion picture idol Kenneth Harlan (who would eventually rack up a total of nine wives). When a friend upset her that summer, she exacted violent revenge. The Daily News reported on August 25, 1929, “Flaming Flo Hart, the titian-haired and tempestuous former ‘Follies’ dancer, was sought by detectives in all the gay Broadway rendezvous last night. She and a blonde young friend, Alice Vail, 18, are charged with brutally beating a young married woman.”

Charlotte Burke had just returned to her apartment from a dinner party at about 2 a.m. that morning when she received a phone call from Flo who said she wanted to return a string of pearls she had borrowed. Charlotte told police “They came a few minutes later, slammed the door as soon as they entered, and then locked it.” The two young women knocked their victim to the floor, ripped her clothing, and stomped her with their high heels. She was taken to a hospital with “156 cuts of the face and body, two fractured ribs, a broken nose, puffy black eyes and internal injuries.”

After champion prize fighter Jack Dempsey retired from the ring he embarked on several enterprises, including a gambling casino in Reno reportedly backed by Al Capone. He also started a vaudeville troupe and recruited Broadway headliner Bee Palmer. The arrangement was not entirely about business. Although Bee was married to songwriter Jack Seigel, there was more between her and Dempsey. She told a reporter from her suite in the Hotel Ogden in 1931 “I left Broadway with my name blazing as a headliner to join his troupe and play the Pantages vaudeville circuit, making fives appearances daily, for which I was never paid.”

When Seigel slapped Dempsey with a $250,000 alienation of affection suit (more than $4 million today) the “former cauliflower champ,” as worded by the Daily News, released a statement “that Bee Palmer never meant anything in his life.” Bee called a press conference of her own in her Hotel Ogden apartment. On March 27, 1931 the Daily News reported “Miss Palmer let it be known that once she learns definite Dempsey made that crack about her meaning nothing to him, she will become a stinging bee and let go a story about the fight ‘that will knock him groggy and set the whole world talking.’”

Gangsters and showgirls in the Hotel Ogden were a common thread. Earlier that year, in February, the body of Vivian Gordon had been found in Van Cortlandt Park. She had been brutally murdered, beaten, strangled, and possibly dragged for some distance behind a car. Vivian had many enemies. She was described by the police as “a woman of many acquaintances” and by The New York Times as being in “the blackmail business.” She was owed money by gangsters, kept a book of some 300 names of important figures—including the Mayor—who hired prostitutes, was known for blackmailing them, and was cooperating with the Hofstadter Committee formed by Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt to probe police corruption.

On March 5 the grand jury heard testimony from a Hotel Ogden resident. The Daily News reported “Among the most significant of the score or more men and women quizzed yesterday was Lillian Franssen, a night club hostess, who lives at the Hotel Ogden and has been an entertainer since the palmer pre-prohibition days when Jacques Bustanoby’s place claimed her talents. What Miss Franssen’s connection with the strangled Vivian was, the district attorney would not divulge.”

Gangsters and executions hit closer to home a month later. Charles Entratter, who sometimes went by the alias Charlie Greene, and his wife, Anna, lived in what the Times Union called “a pretentious apartment” here. The Daily News called Entratter “the Beau Brummel of New York’s gangland,” and the “former bosom pal of Jack (Legs) Diamond.” Entratter was best remembered for his role with Diamond in the 1929 Hotsy Totsy Nighclub murders in Chicago. The Daily News said “Entratter’s acquittal for the murders of William (Red) Cassidy and Simon Walker at the Hotsy Tosty Club was bitterly resented by Red’s brother, Peter, who was wounded in the melee.”

Charles and Anna relocated to New York and moved into their apartment in the Hotel Ogden on April 1, 1931. Charles took a job, supposedly as a beer company sales agent. It was a job that earned him an income large enough to afford fancy clothes and a lavish lifestyle. The Daily News noted “Entratter paid all his bills promptly at the Hotel Ogden.”

On July 3 Anna took a train to Long Beach, California for a few days. The following Monday Entratter was at his desk in his office when he “was rubbed out at 12:45 P.M. by a fusillade of .45-caliber revolver shots fired by three unknown gunman,” according to the Daily News. A manager told police “Without uttering a word, the man pointed a gun at Entratter and blazed away. Entratter fell. Meanwhile, two other men entered, also with drawn guns, and all three fired until their guns were empty. Then they ran.” The article said, “Motives for the murder were almost as thick as his manifold rackets and feuds, with new clues found among his personal papers in the swanky apartment where he lived with his pretty blond wife.”

After champion prize fighter Jack Dempsey retired from the ring he embarked on several enterprises, including a gambling casino in Reno reportedly backed by Al Capone. He also started a vaudeville troupe and recruited Broadway headliner Bee Palmer. The arrangement was not entirely about business.

Around 1935 the building became known as the Hotel Ruxton as the days of gangsters and showgirls drew to a close. Among the residents was Charlotte Epstein, chairman of the United States Olympic Women’s Swimming Committee. She was largely responsible for women’s swimming first being included in the Games at Antwerp in 1920. The New York Times noted “She headed the team that year and again at the games in Paris in 1924 and at Los Angeles, in 1932. She was present in an unofficial capacity at the games in Amsterdam in 1928.” Never married, Epstein sat out the 1936 games in Berlin “because she was opposed to American participation.” She became ill in 1937 and eleven months later, on August 26, 1938, she died in her apartment.

Starting around 1955 one of the ground floor spaces was home to a Slenderella Salon. The chain’s advertisements promised “So-o-o-o EASY for you to be Queen of Hearts at fabulous Slenderella. Every day we’ll mold your figure to those exciting youthful lines every woman wants.” Sessions cost $2 each, or around $20 today.

In 1972 the Szechuan Royal Chinese restaurant opened in a space and would remain for more than a decade. The New York Times food critic reported “It can be said that this is probably as diverse Szechuan menu as we have seen in this city.”

But while things on street level were doing well, the upper floors had seriously declined. On June 1, 1975 The New York Times reported “A 33-year-old ballroom dance teacher was found shot to death in his apartment at the Ruxton Hotel, 50 West 72d Street. The victim, Enrique Crus, who had been shot in the head, was found on the living room floor by his estranged wife, Ivelisse, who had remained on friendly terms with him.”

When attorney and businessman Robert Tannenhauser and his designer husband Marc Donnenfeld purchased the Hotel Ruxton in foreclosure in in 1994, it was a “shipwreck” according to Donnenfeld. The couple initiated a full-building renovation and by July 26, 2010, when The New York Times journalist Christine Haughney wrote about the building, it housed “a lose network of college and post-college friends and their siblings, most of them now in their late 20s and 30s.” Like the renaissance of West 72nd Street in general, the building has regained its former dignity.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

50 West 72nd Street

Next Stop

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 50 West 72nd Street:

Meet Rani Dorman!

Meet Natasha Nesic!

Meet Tina O’Callaghan and Amber Zachweieja !