A “more pleasing type” of architecture

by Tom Miller

In the 1920s both sides of Central Park were seeing the demolition of private homes to make way for modern apartment buildings. The Upper West Side had embraced apartment living decades earlier—beginning with luxury structures like the Dakota, followed by the massive French-style confections that lined Broadway. So when the apartment building craze of the 1920s arrived, the Upper West Side was accepting.

By the last years of the decade, nearly all the old homes on the northern side of the block of West 72nd Street between Central Park West and Columbus Avenue had been demolished. Only three remained in 1928—35, 37 & 39. The New York Times referred to them as “fine private residences” and noted that one was particularly notable. That was the “six-story dwelling at 39 West Seventy-second Street, erected by the late Daniel Loring.”

The Sumptuous house had been home to real estate operator Richard E. La Barre and his wife for many years. The wealthy couple maintained a summer estate in Quoque, Long Island. Now La Barre purchased both 35 and 37 and formed The 37 West Seventy-second Corporation, which would raze the three old homes and erect the latest apartment building.

The group commissioned Harmon & Hart to design the structure. Partners Arthur Loomis Harmon and Donald Purple Hart had recently won the national award for architectural excellence for their Hotel Shelton. The architects produced an eye-catching structure that stood out among the other soaring apartment buildings on the block.

On July 14, 1929 The New York Times reported:

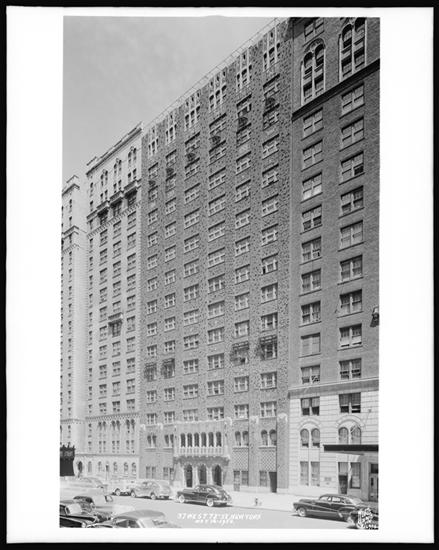

Architecture of a more pleasing type than is usually seen in a modern apartment building is exemplified in the attractive façade of the fifteen-story apartment house nearing completion at 35-39 West Seventy-second Street…The design of the façade is a modern version of North Italian renaissance and is in red brick laid with neat decorative effect.

The “neat decorative effect” included lattice-work patterns, and randomly-projecting bricks that produced a rough, tactile façade. Alternating stone and brick volutes of the arched entrance openings gave an arabesque feeling; while stone columns between the paired arched openings at the second floor were more Mediterranean. The focal point of the lower floors was the elaborate loggia above the entrance with its complex openwork brick and stone railing.

[Gustave Frohman] was already well-known in the business before they started their careers. His long and impressive career included managing Madison Square Theatre in the 1880s; helping to found the Sargent Dramatic School, which became the American Academy of Dramatic Arts; and opening the Lyceum Theatre in 1885.

Harmon & Hart reserved the ornamentation for the two lowest and two highest floors—the central section relying on occasional terra cotta tiles and the stubbly brickwork. “Stone trimming is employed in the two lower and two upper stories,” explained The Times. “Relief has been obtained by the treatment of the brick panels in the lower stories, the stone trimmings and tile inserts around the arcade and by the wrought-iron balconies above.”

The completed building held 84 apartments consisting of two to five rooms. Quintessentially 1920s, the penthouse level was comprised of “three bungalow suites with garden terraces on the roof.” As the building neared completion, The Times noted “All of the old-time private homes on the north side of the Seventy-second Street block have now given way to tall apartments.”

Unlike many Upper West Side apartment buildings that were given names, the new building was known simply as 37 West 72nd Street. It opened just in time for the Stock Market crash of 1929 and the onslaught of the Great Depression. Yet the new residents seem to have been little affected by the economic disaster. The building filled with a wide-range of tenants—from well-to-do attorneys and physicians to theatrical and literary types.

Among the first to move in was retired theatrical manager Gustave Frohman and his wife, Marie Hubert Froham. The brother of Daniel and Charles Frohman, he was already well-known in the business before they started their careers. His long and impressive career included managing Madison Square Theatre in the 1880s; helping to found the Sargent Dramatic School, which became the American Academy of Dramatic Arts; and opening the Lyceum Theatre in 1885. He was one of the first press agents in New York City. Within months of moving in, the 76-year old fell ill. After about a four-week illness, he died in his apartment on the morning of August 16th 1930.

Another resident, 34-year old Julius Girden, had serious misfortune earlier that year. On March 30th the attorney was driving his automobile along Eldridge Street when he was alerted by the screams of women on the street. It was not until he stopped his car that he realized he had struck and killed 6-year old Harry Habit. Girden was arrested at the scene on a technical charge of homicide.

Among the several esteemed physicians in the building at the time was Dr. Michael Schiller, an eye specialist, who lived here with his wife, Madeline, and two sons. Schiller was on the staff of Post-Graduate Hospital and was the chief ophthalmologist of Harlem Hospital.

One of the building’s first employees was doorman Harry Glaser, hired upon its opening. Most likely few of the residents—except perhaps Gustave Frohman—recognized that the 50-year old had been a familiar vaudeville actor at the turn of the century. The years had not been kind to Glaser, however. He lived in a three-room apartment at 88 Amsterdam Avenue, near 64th Street, with his “common-law wife,” Mona Clark. She worked as a hotel chambermaid.

For six years Harry Glaser wore his livery and held the door for well-heeled residents in the 72nd Street building. But his polite demeanor and white gloves hid a dark secret. Both he and Mona were addicted to drugs. The secret was exposed in a horrific tragedy.

On the morning of November 19, 1935 the janitor where Glaser lived, Mrs. Manna McGuffin, ran to Patrolman Charles J. Gordon, telling him she had heard gunshots. As Gordon approached the building, Glaser rushed out screaming. Bleeding from two gunshot wounds, he collided with the officer. Upstairs, police found 52-year old Mona Clark dead. Glaser had murdered her at around 10:40 as she lay in bed. The New York Times reported “Glaser then fired two shots into his own body…One of the bullets entered Glaser’s left breast and the other had lodged against his right temple.”

He told Patrolman Gordon “that lack of money to buy narcotic drugs had caused this act.” Drug paraphernalia was found in the apartment. Sadly, other items were found there that harkened back to happier times for the former thespian. “In two old theatrical trunks were found papers and photographs that indicated Glaser had been a member of ‘Vincent’s Comedy Musical Artists.’ Photographs of Nora Bayes, Jack Norworth, Lew Dockstader and B. F. Keith were also found.”

In December 1937, famed Russian-born writer and director, Theodore Komisarjevsky, leased an apartment here. Noted for his groundbreaking productions of plays by Chekov and Shakespeare, he had lived and worked in London for over a decade. Newspapers were highly excited when the news of his lease-signing was reported.

Komisarjevsky had a reputation as a womanizer and his second marriage, to actress Peggy Ashcroft, had ended a year earlier. Famous British stage actress Edith Evans reportedly called him “come-and-seduce-me.”

Hal Steffen and his wife, Alma, were in the building at the time. Steffen was called by The New York Times “a leader in his field” for his photojournalism. He had joined the Bain news Service in 1904 and by now had earned a reputation for his often- gripping journalistic photographs. Alma Mueller Steffen, meanwhile, had taught in Public School 11 at 314 West 21st Street since 1918. Steffen died in the apartment on April 13, 1937. Within the year, Alma died at the age of 46.

Colonel James A. Moss was also a resident of 37 West 72nd Street. He was President General of the United States Flag Association, which annually presented an award for patriotism. On Thursday, April 24, 1941, the Patriotic Service Cross was scheduled to be given to Harold L. Rowland, president of the Hotel Pierre, by Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. On Wednesday evening Colonel Moss picked up the award in anticipation of the next day’s ceremony.

Komisarjevsky had a reputation as a womanizer and his second marriage, to actress Peggy Ashcroft, had ended a year earlier. Famous British stage actress Edith Evans reportedly called him “come-and-seduce-me.”

Moss caught a taxicab and was “within a few feet of his home,” according to The New York Times, when an inter-city bus slammed into the cab, demolishing it. Colonel Moss was killed instantly. The tragedy necessarily caused a change in plans at City Hall the following day.

“This cross was in the possession of Colonel Moss when he was killed, and therefore it will be necessary to give it to Mr. Rowland at a later date,” explained Mayor La Guardia. Instead, he took advantage of the moment to eulogize Moss, calling him “An American of the highest type, believing in the ideals and institutions symbolized by the flag of the United States.” The Mayor said Moss had been “a fine American, a great soldier, a military expert, and a kindly, lovable American.”

Following in Moss’s footsteps was the American Action Committee, which had its headquarters in the building in 1960. That year Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was scheduled to arrive in New York for the 902nd Plenary Meeting of the United Nations General Assembly. It would forever be remembered as Khrushchev’s “shoe-banging incident.”

Prior to the leader’s arrival, the American Action Committee poised to denounce the Soviet Union. It organized a rally in Central Park on September 17, Constitution Day. During the event, a resolution “calling for the Soviet Union to be expelled from the United Nations” was adopted. Fliers were distributed that invited protesters to be at Pier 73 on East 25th Street where Khrushchev was to arrive at 7 a.m. on Monday, September 26, 1960.

“Let us all be there at 6 A.M. to give Khrushchev and his gang the welcome they deserve,” it read. The group also distributed black stickers with red lettering “Khrushchev Not Welcome Here.”

Little has changed to Harmon & Hart’s “pleasing” façade in its nearly 90 years. As it did in 1929, it manages to stand out distinctly among the cliff-wall of 1920s apartment buildings lining the block.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT